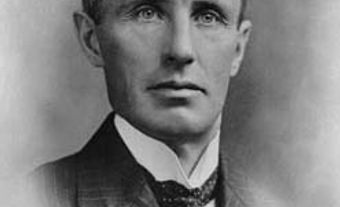

Richard Bedford Bennett, 1st Viscount Bennett of Mickleham, Calgary and Hopewell, businessman, lawyer, politician, philanthropist, prime minister of Canada 7 August 1930 to 23 October 1935 (born 3 July 1870 in Hopewell Hill, NB; died 26 June 1947 in Mickleham, England). R.B. Bennett is perhaps best remembered for his highly criticized response to the Great Depression, as well as the subsequent unemployment relief camps and the On to Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot. However, he also created the Bank of Canada, the Canadian Wheat Board and the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission, which became the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He also oversaw Canada’s signing of the Statute of Westminster. For his service during the Second World War, he was appointed to Britain’s House of Lords and became Viscount Bennett of Mickleham, Calgary and Hopewell.

Early Years

Richard Bedford Bennett was born in the tiny community of Hopewell Hill, New Brunswick, in July 1870. His family had once prospered in the shipbuilding business; but at the time of his birth they were suffering in poverty.

A serious young man and a voracious reader, Bennett was an exceptional student with a prodigious memory. He graduated high school at age 15 and a year later was teaching school. By 18, he was a principal. When school was on break, he worked in law offices. He left education to enrol at the Dalhousie University law school. Conservative senator James A. Lougheed offered him a position in his Calgary law firm. Bennett negotiated a partnership deal, creating the firm Lougheed Bennett. In January 1897, Bennett moved west.

Law Firm and Business Success

Bennett excelled at corporate law. His firm included such clients as the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Hudson’s Bay Company. He and his childhood friend Max Aitkin (later Lord Beaverbrook) also worked together in a number of successful ventures, including stock purchases, land speculation and the buying and merging of small companies. Bennett became president of a host of companies and served on the boards of many others.

Before he was 40, Bennett was a multi-millionaire. He lived at the Palliser Hotel in Calgary. He neither smoked nor drank alcohol. He dated a number of women but never married. He also began a lifelong dedication to philanthropy, giving generously to schools, hospitals, charities and individuals in need.

Early Political Career

Bennett graduated from law school in 1893 and was elected to serve on the Chatham municipal council in 1896. He rekindled his political ambitions in Calgary when, in 1898, he won election to the Assembly of the North-West Territories. His ability to speak quickly, extemporaneously and persuasively earned him the nickname Bonfire Bennett. Alberta became a province in 1905 and Bennett became its first Conservative Party leader.

In 1911, Bennett entered federal politics; he was elected the Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Calgary. He was disappointed when Prime Minister Robert Borden did not appoint him to the Cabinet. He nonetheless made a name for himself as a hard worker and persuasive speaker. Among other things, he led an effort that uncovered corruption in the Canadian Northern Railway. However, Bennett was dissatisfied with his role as a backbencher and did not run for re-election in 1917.

Conservative Party Leader

In 1921, Prime Minister Arthur Meighen appointed Bennett the minister of justice. But Bennett failed to win a seat in the subsequent election by only 16 votes. In 1925, he became the federal member for Calgary West. In 1926, he served as minister of finance; acting minister of the interior; acting minister of mines; and acting superintendent general of Indian affairs. After Meighen resigned following his short-lived government’s defeat, Bennett became the national Conservative Party leader and leader of the Opposition in October 1927.

Bennett worked hard to unify the party, expand its base and shore up its finances. (He personally donated $1.1 million to the party in the three years after becoming leader.) The 1930 election saw Canadians voting while in the early months of the economically and socially devastating Great Depression. Liberal prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King said he would let markets fix the worsening catastrophe. Bennett promised to fight vigorously to create jobs, help the millions of unemployed and “blast” Canada back into world markets. In July 1930, the Conservatives won a commanding majority and Bennett became prime minister.

Prime Minister

Bennett’s government undertook various initiatives to help Canadians suffering from the effects of the Depression. The Unemployment Relief Act, 1930 created jobs by providing $20 million for public works. It was later augmented by the Unemployment and Farm Relief Act, 1931, which provided for more infrastructure construction and direct relief for farmers and the unemployed. Western farmers had been devastated by a collapse in prices, a drought, and a grasshopper plague. Bennett’s government made farm loans easier to acquire with the Farmers’ Creditors Arrangement Act. In 1935, the Bennett government created the Canadian Wheat Board, which stabilized prices and helped farmers sell their wheat abroad. To increase trade, Bennett convened the Imperial Economic Conference in Ottawa. (See Colonial and Imperial Conferences.) It resulted in 60 per cent more Canadian goods being sold in Britain and bilateral trade agreements with other nations.

At that time, chartered banks controlled interest rates, the value of the Canadian dollar in world markets and the amount of money in circulation. They even printed their own currency. Bennett established a Royal Commission as a step toward creating the Bank of Canada. It would ultimately assume all those powers from the chartered banks. The chartered banks fought the idea, but Bennett persevered. The Bank of Canada Act was passed in 1934 and the Bank opened in 1935. It eventually gained the legal mandate to control Canada’s monetary policy at an arm’s length from the federal government.

Bennett believed that Canada’s culture was being swamped by the United States; especially with regards to the dominant cultural force of the day — radio. In 1932, his government created the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC), which regulated radio broadcasting to ensure more Canadian content. It also established a publicly owned, national radio network dedicated to telling Canadian stories to Canadians. In 1936, it became the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). (See also Founding of the CBC.)

In 1930, Bennett represented Canada at the imperial conference at which the Statute of Westminster was drafted. The Statute represented a significant step toward Canada’s independence by ensuring that Britain could no longer pass legislation applicable to any of its dominions. (See also Editorial: The Statute of Westminster, Canada’s Declaration of Independence.)

However, under Bennett’s tenure, the Depression worsened. He had promised aggressive action to combat the effects of the economic downturn, but in office found it difficult to develop a coherent program. His business instincts did not always serve his political interests. His initiative to persuade the British Empire to adopt preferential tariffs brought some economic relief to Canada, but not enough. By 1933, the nadir of the Depression, Bennett appeared indecisive and ineffective. He became the butt of endless jokes. Cars towed by horses because owners could not afford gasoline were dubbed “Bennett buggies.”

By 1934, Bennett was increasingly isolated and faced major dissent both in his party and the country. Through all this, he was often touched by letters Canadians wrote to him about the hard times they were facing. He regularly responded with personal notes, often tucking some cash into the envelopes.

Unemployment Relief Camps and Regina Riot

In 1932, various Western mayors and premiers demanded that Bennett do something about the thousands of unemployed young men who were loitering in cities and towns. In October, Bennett created unemployment relief camps. They offered young men food and housing while working to cut trees, build roads and perform other manual labour. However, workers at the camps were given a stipend of $0.20 per day for a 44-hour workweek, which was largely seen as insufficient.

In spring 1935, strikes at many of the camps turned into a months-long protest in Vancouver. On 3 June, around 1,000 men left British Columbia aboard trains on their way to negotiate directly with Bennett. Bennett believed this On to Ottawa Trek was organized by communists (the Workers’ Unity League, which organized the protests, was affiliated with the international Communist movement) and therefore threatened law and order. He directed that it be stopped. On 1 July, the RCMP moved on the trekkers in Regina, even though the leaders had decided to end the trek. The ensuing riot injured many and killed a police officer and a protester. Bennett was harshly criticized for his reaction to the Trek.

Rioters converge on police officers and an injured man.

Bennett’s New Deal

In January 1935, with the federal election later that year, Bennett made five radio speeches. He argued that the Depression proved capitalism was failing and that more government intervention was needed. He proposed improving or creating federally run unemployment insurance, universal health insurance, pensions and other forms of social welfare. Some critics attacked Bennett’s tone, others his ideas. Though his plans were consistent with beliefs and policies he had been promoting for years, some said he was simply copying American President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. They derided his speeches as Bennett’s New Deal.

Canadians went to the polls on 14 October 1935. Bennett cabinet minister Henry Herbert Stevens had defected from the Conservative Party and formed the Reconstruction Party. Though it won only one seat — Stevens’s in British Columbia — it ran candidates in 172 of the 245 ridings and took votes that likely would have gone to Bennett’s Conservatives. Other new parties, such as the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and Social Credit, further split the vote in many ridings. Although the Liberal Party’s percentage of the popular vote was close to what it had been in 1930, it took 171 seats. Bennett’s Conservatives won only 39. Other parties took 35.

Leader of the Opposition

Bennett had suffered a heart attack in March 1935 and was personally devastated by the electoral rebuke. However, he acted as an effective leader of the Opposition. An excellent parliamentary debater, he attended the House of Commons almost every day and asked blistering questions of the government. He also supported the rebuilding of the Conservative Party. He resigned as Conservative Party leader in March 1938 due to health concerns. Robert Manion became his successor at the party’s July convention.

Viscountcy

Bennett realized a lifelong dream to live in England when he purchased a 94-acre estate in Surrey called Juniper Hill. It was close to his old friend Lord Beaverbook, who had moved to England years before. After living in Calgary’s Palliser Hotel and the Château Laurier Hotel in Ottawa, it was the first home Bennett ever owned.

In England, Bennett accepted numerous speaking engagements and served on various boards. At the outset of the Second World War, Lord Beaverbook was appointed the minister of aircraft production. Bennett worked as his assistant, arranging the building of planes and airfields. For his service in the war effort, British prime minister Winston Churchill appointed him to the House of Lords; he became Viscount Bennett of Mickleham, Calgary and Hopewell. Prime Minister Mackenzie King, Bennett’s political rival, exempted Bennett from Canada’s long-standing policy to forbid such appointments.

By 1947, Bennett’s health was declining. In March, he sold nearly all his investments. He made generous donations to Canadian charities, churches, schools and scholarships, with special attention to Dalhousie University and Mount Allison University. On 26 June 1947, Bennett was enjoying a warm bath when he suffered a fatal heart attack. He is the only Canadian prime minister buried outside Canada.

See also Timeline: Elections and Prime Ministers.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom