William Avery (Billy) Bishop Jr., VC, CB, DSO & Bar, MC, DFC, ED, First World War flying ace, author (born 8 February 1894 in Owen Sound, ON; died 11 September 1956 in Palm Beach, Florida). Billy Bishop was Canada’s top flying ace of the First World War; he was officially credited with 72 victories. During the Second World War, he played an important role in recruiting for the Royal Canadian Air Force and in promoting the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

Early Life

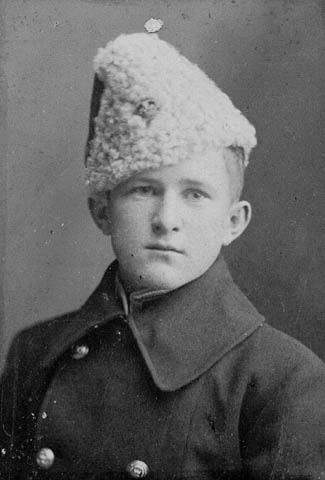

First World War flying ace, William Avery (Billy) Bishop Jr., was born in Owen Sound in 1894. His father, William Bishop Sr., was a lawyer and the county registrar. William Bishop Sr. married Margaret Greene in 1881 and began construction on the Bishop home in 1882, which was completed in 1884. Billy grew up at 948 3rd Avenue West with his older brother Worth and younger sister Louise; his other older brother, Kilbourn, had passed away in 1892.

Growing up, Billy Bishop was an outdoorsman and enjoyed riding, shooting and swimming. He also exhibited a keen interest in flight at an early age. As a boy, he crafted his own flying machine from an orange crate and bed sheets. He “flew” his craft from the roof of the house, only to land in his mother’s rose bushes.

Education

Bishop attended Beech Street School (later renamed Dufferin Public School in 1910), just down the street from his home. As a teen, he attended the Owen Sound Collegiate Institute before enrolling at Royal Military College (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario.

In the fall of 1911, Bishop began as a cadet at RMC. In his senior year, war broke out and, like many of his classmates, Bishop enlisted. He was given an officer’s rank and with his horseback riding experience and fine shooting skills, he was assigned to the cavalry.

Lieutenant Bishop began his military career in August 1914 with the Mississauga Horse Regiment. However, he was unable to sail overseas with his division on 1 October, as he had pneumonia. After his release, Bishop was reassigned to the 7th Canadian Mounted Rifles in London, Ontario. He and his division departed on 8 June 1915 and sailed overseas aboard the Caledonia. They arrived in England and were stationed in Shorncliffe military camp.

To The Skies

One day in July 1915, Bishop saw an airplane land in a nearby field and then take off again; this event would change the whole direction of his career.

It was the mud, I think, that made me take to flying… I had succeeded in getting myself mired to the knees when suddenly, from somewhere out of the storm, appeared a trim little aeroplane.

It landed hesitatingly in a near-by field as if scorning to brush its wings against so sordid a landscape; then away again up into the clean grey mists.

How long I stood there gazing into the distance I do not know, but when I turned to slog my way back through the mud my mind was made up. I knew there was only one place to be on such a day — up above the clouds in the summer sunshine.

William A. Bishop, Winged Warfare

Bishop discovered that it would be six months before he could be trained as a pilot, but if he became an observer, he could be admitted immediately. Bishop applied for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps and became a RFC observer in September 1915. He was stationed with the No. 21 Squadron and went to the front lines in January 1916, where the Squadron flew missions deep into enemy territory.

A knee injury and some health complications delayed Bishop’s pilot training until October 1916. He began his ground training at the School of Military Aeronautics in Oxford. Due to his experience as an observer, he achieved top marks in the meteorology, radio and navigation classes. He was soon sent to Upavon Flying School on Salisbury Plain to begin his flying lessons. His final stage of training was an advanced course at No. 11 Squadron that included night flying. Bishop received his wings in November 1916. In early December he was assigned to 37 (Home Defence) Squadron, a night-fighter unit based in Essex.

Flying Ace

In March 1917, Bishop was sent to the front lines in France where he joined No. 60 Squadron at Filescamp Farm. He had to wait until March 25 for his first real fight in the air, which ended with Bishop shooting down his first German Albatross airplane and barely gliding back over the line to safety.

By the end of May, Bishop had recorded 22 victories. His most famous exploit, however, happened in the early morning on 2 June 1917 — according to Bishop, he flew across enemy lines and attacked a German aerodrome, shooting down three German planes. He managed to make his way back to his squadron by flying directly under four enemy airplanes. (Bishop’s account of the raid would become a focus of debate decades later.)

On 29 August 1917, Bishop arrived at Buckingham Palace, where King George V presented him with the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross for his actions up to the end of May, as well as the Victoria Cross for his actions on 2 June 1917. In September, he received his fourth decoration, a bar for his Distinguished Service Order.

The Flying Foxes

In September 1917, Bishop was granted leave and went back to Canada. He decided to write about his adventures and soon completed his book Winged Warfare. On 17 October 1917, Bishop married his sweetheart, Margaret Burden, at Timothy Eaton Memorial Church in Toronto. At the end of October, he was assigned to the British War Mission in Washington, DC.

In 1918, he returned to England with his wife and became the Commander of the new No. 85 Squadron, nicknamed the Flying Foxes. In May 1918, the squadron completed training and moved to the front lines in France, where they were stationed at Petit Synthe. The squadron flew the new S.E. 5a airplanes. It was then posted to St. Omer on 8 June 1918.

On 16 June, Bishop received a message recalling him to England to organize a Canadian flying corps; by that time, he had recorded 62 victories. Within the next three days, Bishop was credited with 10 additional victories, bringing his total to 72 enemy aircraft. On 19 June, his final day in France, Bishop shot down five German airplanes in 12 minutes. This feat earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross, which he was awarded on 3 August 1918.

Upon his return to England, Lieutenant Colonel Bishop became the commanding officer designate of the Canadian Wing of the Royal Air Force. Around this time, the French government awarded him the Legion of Honour and the Croix de Guerre with two palms.

In October 1918, Bishop and his wife, Margaret, returned to Canada. Bishop met with government leaders and gave public speeches to encourage enlistment in the air force. In early November, he sailed for England. On 11 November 1918, halfway across the Atlantic, the ship received news that the Great War had ended.

Interwar Years

In 1919, Bishop began a lecture tour across North America, speaking about his wartime adventures. In March of that year, Bishop’s tour was put on hold after he collapsed on stage — he was later diagnosed with appendicitis. After recuperating, he resumed his lecture tour, but the public’s interest had dwindled.

In 1919, Bishop went into business with fellow Victoria Cross winner William Barker. They created Bishop-Barker Aeroplanes Limited, which provided passenger service from Toronto to the Muskoka Lakes. The partners also signed a contract with the Canadian National Exhibition to stage a daily show of aerobatics. However, after diving towards the grandstand during a show, their contract was cancelled. The company soon changed from passenger service to an airfreight delivery service, but shortly after, in 1921, Bishop was injured in a crash landing and the company eventually dissolved.

By the end of 1921, Bishop had returned to England as a sales representative for his friend Gordon Perry’s company, which sold the foreign rights to the Delavaud process of making cast iron pipe. During that time, Bishop was based in London.

In 1928, he dined in Berlin at the Berlin Aero Club with his former foes and was made a member of the German Ace Association, the only non-German to receive such an honour.

Bishop’s fortune was wiped out in the stock market crash of November 1929. His old friend Gordon Perry offered him the position of Vice President of Sales with McColl-Frontenac Oil in Montreal, Quebec. The family moved back to Canada in 1930.

Second World War

Bishop had maintained his connection with the Royal Canadian Air Force since the First World War and was appointed Honourary Group Captain of the RCAF in 1931. In 1934, Bishop began taking flying lessons to requalify for his license.

In 1936, Bishop was made an Honourary Air Vice Marshal by William Lyon Mackenzie King. In this position, he advocated more funds and expansion of the Royal Canadian Air Force. On 10 August 1938, Bishop was appointed Honourary Air Marshal and made head of the Air Advisory Committee.

Canada declared war against Nazi Germany in September of 1939. In December, the Canadian government agreed to a proposal that Canada become the training centre for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

On 23 January 1940, Bishop became Director of Recruiting for the RCAF, and the family moved to Ottawa, Ontario. He maintained a hectic schedule of travelling and speaking, but keeping up this pace was taking its toll. (In addition to his RCAF duties, Bishop had a cameo role in the 1942 Warner Bros. film Captains of the Clouds, which starred James Cagney.) On 7 November 1942, while making a speech in Hamilton, Ontario, he felt an excruciating pain in his stomach. He was flown to Montreal, and rushed to the hospital where he was diagnosed with acute inflammation of the pancreas, which required an immediate operation. When Bishop was discharged from the hospital in January 1943, he went on medical leave.

He returned to his recruiting duties in March 1943 with more energy than ever. Bishop also completed a second book, Winged Peace(1944), which contained his views on the future of aviation. However, by his 50th birthday on 8 February 1944, he was close to total exhaustion.

After D-Day (6 June 1944), recruitment for aircrews stopped, even though victory had not yet been won. Bishop asked to be relieved of his duties by the end of the year. He was made a Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath on 1 June 1944, as part of King George VI’s Birthday Honours.

Post-War Period

After the war ended in 1945, Bishop returned to Montreal and the oil business. He was semi-retired and spent many hours reading in his private library or engaging in various hobbies such as ice carving, soap carving or wood carving. Bishop would dress in his uniform on occasions such as Battle of Britain Day parades and Remembrance Day services.

When the Korean War began in 1950, Bishop volunteered his services, but he was politely declined. In 1952, he retired from McColl-Frontenac and began spending his winters in Florida. Bishop died peacefully in his sleep on 10 September 1956 in his Florida home. He was survived by his wife, Margaret (died 1979?), and by his two children, Arthur (1923–2013) and Margaret Marise (1926–2013).

His death was reported around the world and Bishop was given a military funeral at Timothy Eaton Memorial Church. Twenty-five thousand people lined the funeral procession route. Bishop’s body was cremated, and his remains were interned at Greenwood Cemetery in his hometown of Owen Sound.

Controversy

In 1982, a National Film Board of Canada production, Paul Cowan's The Kid Who Couldn't Miss, challenged the veracity of many of Bishop's claims, including his own account of the raid which won him his Victoria Cross. The film caused a furor in Parliament and the media. Investigation by a Senate sub-committee exposed a number of errors in this apparent "documentary" and confirmed that statements had been wrongly attributed and incidents shifted in time for dramatic effect. However, the senators were unable to demonstrate conclusively that Bishop's claims were valid and consequently recommended only that the film be labelled as "docu-drama."

Since then, the controversy has continued. In 2002, Brereton Greenhous (former Department of National Defence historian) published The Making of Billy Bishop, in which he claimed that the First World War ace had lied about the raid of 2 June 1917. However, other military historians, including Peter Kilduff and David Bashow ( Royal Military College), have argued against this view.

Towards the end of his life, Bishop freely admitted that he had embellished some accounts of his flying exploits in popular publications such as Winged Warfare. However, according to Bashow, Bishop’s combat reports were very professional and tended to understate his success — these were the same reports upon which his Victoria Cross and other decorations were based.

Given the many gaps in British and German records (including the destruction of documents during bombing campaigns in the Second World War), historians have not been able to confirm all of Bishop’s combat claims — Kilduff, for example, could only confirm 21 of 72 victories. As the evidence is inconclusive, it is unlikely that the debate will ever be settled.

Without doubt, Bishop was both brave and skilled. Whether or not his combat claims were exaggerated, his daring and his success were an inspiration during the First World War.

Honours

- Victoria Cross (1917)

- Distinguished Service Order with Bar (1917)

- Military Cross (1917)

- Distinguished Flying Cross (1918)

- 1914–1915 Star (1918)

- British War Medal (1918)

- Victory Medal with Mentioned in Dispatches Emblem (1918)

- Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (1918)

- Croix de Guerre avec Palmes (1918)

- George V Jubilee Medal (1935)

- George VI Coronation Medal (1937)

- Companion of the Order of the Bath (1944)

- 1939–1945 War Medal (1945)

- Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953)

- Canadian Efficiency Decoration

- Canadian Volunteer Service Medal

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom