The Wartime Elections Act of 1917 gave the vote to female relatives of Canadian soldiers serving overseas in the First World War. It also took the vote away from many Canadians who had immigrated from “enemy” countries. The Act was passed by Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Conservative government in an attempt to gain votes in the 1917 election. It ended up costing the Conservatives support among certain groups for years to come. The Act has a contentious legacy. It granted many women the right to vote, but it also legitimized in law many anti-immigrant sentiments.

Conscription

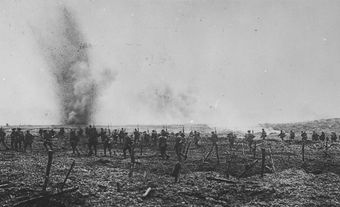

Robert Borden’s Conservative government had introduced conscription in May 1917, to bolster Canadian fighting forces in the First World War. Conscription deeply divided the country; English Canadians were largely in favour, while French Canadians and others not of British descent were opposed. The Conservatives feared that opponents of conscription, including the opposition Liberal Party, would join forces to defeat the Conservatives in the upcoming general election in December.

Election Moves

Borden made several political moves to strengthen his position ahead of the election. He convinced many pro-conscription Liberals and other opposition MPs to join the Conservatives in a Union government to push for conscription and steer the Canadian war effort.

Borden also changed the rules about who could and could not vote in the coming election by introducing the Wartime Elections Act. The Act was designed to create legions of new voters who were likely to support the Unionists, and to disenfranchise voters who would likely be opposed to conscription.

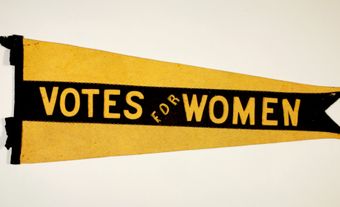

On 20 September, after an angry debate, Parliament passed the Act. The new law disenfranchised Canadian citizens who had been born in “enemy” nations after March 1902; although it exempted those citizens who had a son, grandson or brother on active duty in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Meanwhile, the Act granted the vote to the wives, mothers and sisters of serving soldiers; as well as to women serving in the military. ( See also Canadian Women and War.) This was the first time Canadian women were granted the right to vote in federal elections.

Most Canadians supported conscription and the war effort; they therefore also supported the Act.

Aftermath

The Act undoubtedly increased support for Borden’s party. It was not ultimately a major factor in the 1917 election, though, which the Unionists won. However, for decades afterward, Conservative support in Quebec, and among some ethnic and immigrant groups, was badly damaged.

In the vote on 17 December 1917, some 500,000 Canadian women participated in a federal election for the first time. The Act was repealed at the end of the war; but by 1918, all women born in Canada over the age of 21 would permanently gain the right to vote in federal elections.

The legacy of the Wartime Elections Act is contentious. It granted many women the right to vote, but it also legitimized in law many anti-immigrant sentiments.

See also Women’s Suffrage in Canada; Indigenous Suffrage; Black Voting Rights in Canada; Military Service Act; Wartime Home Front.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom