Inuit and subarctic Indigenous peoples have traversed the North since time immemorial. Indigenous knowledge and modes of transportation helped early European explorers and traders travel and survive on these expanses. Later settlement depended to an extraordinary degree on the development of transportation systems. Today, the transportation connections of northern communities vary from place to place. While the most remote settlements are often only accessible by air, some have road, rail and marine connections. These are often tied to industrial projects such as mines.

Indigenous Transportation in the North

Traditionally, the Inuit inhabitants of the Arctic were hunters and gatherers who moved seasonally from one camp to another. The Inuit used sleds and skin-covered boats, with regional variations in both design and use. Dogs pulled sleds and served as hunting animals, locating seal breathing holes in the sea ice, hunting muskoxen, holding bears at bay and serving as pack animals in the summer (see Canadian Inuit Dog; Dogsledding). Men used single-seat kayaks for hunting sea mammals, and for hunting caribou in rivers and lakes. In the Beaufort Sea and along the Alaskan coast, large skin-covered umiaks were used for whale hunting, although in the Canadian Arctic (and Greenland) women more often used such boats to transport households from place to place.

Subarctic Indigenous peoples used snowshoes, toboggans, canoes and sleds. Survival for these mobile peoples depended on being able to travel long distances. Snowshoes were essential for winter travel. Heavy loads were transported on toboggans and sleds were pulled both by dogs and people. During the summer, people travelled with their belongings in canoes on rivers and lakes.

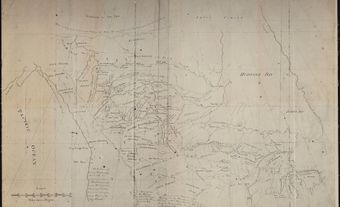

Exploration and the Fur Trade

Water transport was the first means by which Europeans accessed the North. Explorers came from the east by sea, fur traders from the south via the Mackenzie River and the east via Hudson Bay, and, much later, whalers from the west, around Alaska. After early European efforts to find the Northwest Passage, the first organized transport among non-Indigenous peoples in the North was connected with the fur trade. Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) ships sailed trade routes in the eastern Arctic, while canoes and other small craft travelled routes in the West (see Birchbark Canoe; York Boat).

In Canada’s early days, settlement took place mainly in the South. Connecting southern settlements to the North via roads was prohibitively expensive. As the country industrialized, railways were occasionally proposed to link the North with the South. None of these schemes was feasible, however.

Population and economic development north of the 60th parallel did not justify the expense of roads and railways, and so the North continued to be served by water. This fact meant that for seven to nine months of the year, transportation was blocked by ice. Along the Mackenzie River, virtually continual water transport was possible from the railhead at Waterways (now Fort McMurray), in northern Alberta, all the way to the Arctic Ocean. There was one major portage, on the Slave River near Fort Smith, and shipments depended to a high degree on water levels in the southerly parts of the system. The HBC dominated the traffic and maintained a small fleet of steamships to carry it.

Air Transportation and Mining

Transportation was revolutionized by the appearance of the airplane. Bush pilots, often air-force veterans from the First World War, could take their small craft where no boat could go (see Bush Flying). Better still, an airplane was virtually an all-season craft. The North’s winter isolation was finally broken. Using airplanes, prospectors could work more efficiently. A prospecting boom was followed by mining development, particularly at Yellowknife and at Great Bear Lake.

Mining development raised traffic volume along the Mackenzie and created a demand for competition to undercut the rates charged by the HBC. Several companies arose, of which the most enduring was Northern Transportation Company Ltd., which became a subsidiary of Eldorado Gold Mines Ltd. (later Eldorado Nuclear Ltd.), a uranium- and radium-producing company. Meanwhile the bush pilots’ operations were being amalgamated into larger entities, particularly Canadian Pacific Air Lines, a CPR subsidiary.

Transportation in the North since the Second World War

The Second World War brought further changes. The Alaska Highway was built from northern British Columbia through the southern Yukon. This opened the North to road traffic for the first time, as well as demonstrating that an all-weather road was possible. The US army developed airfields and an oil pipeline in the Mackenzie Valley, again augmenting traffic volumes in that area. Wartime saw the appearance of new and bigger airplanes, especially the DC-3 and DC-4, making air cargo something more than a luxury for the first time. Just after the war, the HBC abandoned its riverboat business, leaving the field to Northern Transportation Company Ltd., which by then had become a federal crown corporation.

Northern Transportation greatly expanded its operations, particularly after the construction of the DEW Line in the mid-1950s (see Early-Warning Radar). The company operated as a common carrier down the Mackenzie and into the Arctic Ocean, west to Alaska and east to the Arctic Archipelago. In 1975, it set up a branch in Churchill, Manitoba, to serve the Keewatin coastal settlements on the western side of Hudson Bay. In 1985, Northern Transportation was sold to an Inuit corporation and thus ceased to be a crown corporation.

With the mass production of the personal snowmobile in the 1960s, many Northern Canadians became much more mobile and connected. In the Arctic, the snowmobile changed the hunting, herding and trapping patterns of the Inuit. The vehicle largely replaced the dogsled.

Airports were improved to handle the larger aircraft of the postwar period. The White Pass & Yukon Route railway had been built between Whitehorse and Skagway, Alaska, at the turn of the century; in 1964, the Great Slave Lake Railway was completed linking Alberta with Great Slave Lake. A regular highway was built linking Yellowknife with northern Alberta. Ice roads, connecting such places as Great Bear Lake with Yellowknife, could also be established and kept open during the long winter. Air service increased, as did expenditure on airports.

Did you know?

The Dempster Highway linking Dawson to Inuvik — and extended to Tuktoyaktuk in 2017 — is Canada’s northernmost highway. The 138 km extension, called the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway, is Canada’s first all-season road to the Arctic Ocean. Before 2017, a winter ice road reached Tuktoyaktuk over the frozen Mackenzie River.

The Canadian Coast Guard operates six icebreakers in northern waters. These ships help clear routes for cargo vessels that supply northern communities.

Transportation of Exports in the North

Exports of Prairie grain were dispatched overseas annually from Churchill, Manitoba, starting in 1931. The closure of the town’s port in 2015 halted grain shipments for several years. These shipments resumed when the port reopened under new owners in 2019.

In Nunavut, exports of lead and zinc concentrate left Nanisivik from 1977 until 2002, when the mine and settlement closed. The Polaris mine on Little Cornwallis Island also shipped exports of lead and zinc concentrates by sea from 1982 until its closure in 2002. Today, the Mary River Mine on Baffin Island ships iron ore directly to foreign markets. However, most exports from northern mines first travel south by road or rail before being shipped on to their destination markets. Oil and natural gas are transported south by pipeline.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom