Stage and Costume Design

Historical evidence suggests that in Canada by the late 18th and early 19th century resident amateur and professional theatre companies alike recognized the value of well-conceived scenery and costuming for the critical and financial success of a production, and accordingly allocated significant portions of their budgets to this aspect of theatrical creation. The notion of a professionally trained theatre designer, however, remained relatively unknown, and artists were instead conscripted from the fine arts of landscape and portrait painting. At the end of the 19th century, the Canadian stage was dominated by American syndicates and British touring companies which largely curtailed the growth of an indigenous design tradition. One notable exception was the Canadian touring company the Marks Brothers. Operating out of Christie Lake, Ontario, from the 1870s until the 1920s, the Marks Brothers regularly employed scene painters for their tours and, despite the major difficulties involved in transporting equipment and materials across the country, nonetheless featured elaborate stage settings and costumes in their shows.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Canadian stage and costume design continued to reflect the practices and standards of London and New York. The American influence was absorbed through visits to New York, contacts with theatre departments in American universities, and through continued touring productions. British standards were introduced by talented individuals who visited or chose to live here. Until the 1950s, there was minimal recognition of scenic and costume design as an art. At the DOMINION DRAMA FESTIVAL, the amateur competition formed in 1932 and held annually from 1933 to the 1970s, there was no travel allowance for designers, and initially no design award was made. Although this was later rectified with an award honouring Martha Jamieson, the producing group's (and not the designer's) name went onto the plaque.

Established amateur companies copied sets of the original productions or asked local artists to provide them. In the 1920s and 1930s, some well-known painters, particularly the members of the GROUP OF SEVEN, designed sets and costumes for the Hart House Theatre and the Arts and Letters Club in Toronto. Firms which rented formal wear introduced costume departments; Malabar's, now an international concern, began this way. Yet, the costumes were the work of anonymous sewers and pattern drafters, not designers.

As professional theatre, ballet and opera companies were established and the CBC began TV broadcasting in the 1950s, opportunities for designers were suddenly provided, though there were few designers and fewer technicians (seeBROADCASTING, RADIO AND TELEVISION; TELEVISION PROGRAMMING.) Initially, many of the CBC set designers were European. But it was the STRATFORD FESTIVAL- as well as Tanya Moiseiwitsch, who designed its stage and first productions - that made Canadian artists aware of the possibilities in theatrical design.

As Nunavut marks 20 years as a territory, Leah and Falen shout out mother, grandmother, educator, knowledge keeper and award winning artist Atuat Akittirq.Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Young Canadians, many still at art schools and universities, were employed as technicians and, with their Stratford training, became the core of the designers working at the regional and festival theatres in the late 1960s and the 1970s.

In the 1950s, the Ontario College of Art, which taught the fine arts of painting and drawing, also played an important role in preparing the first generation of home-grown talent such as Marie Day, Murray Laufer, Martha Mann and Suzanne Mess for work in the design field. Professional training programmes specific to theatrical costume and set design followed in the 1960s, first at the National Theatre School (1960), and later within university programmes such as the University of Alberta's four-year BFA in Design (1966). Nevertheless, many designers continued to seek professional training elsewhere, especially in the United States and Europe.

Moiseiwitsch continued to work at Stratford for the next 30 years. Other British designers followed. Leslie Hurry contributed most of his important designs to the festival: in fact, some of his best work was done in Canada. Desmond Heeley's spare yet exotic designs have made their mark on this country. Susan Benson brought a control of texture and palette that has influenced many younger designers. In the 1980s, Canadian designers, educated and trained in this country, assumed a principal role at the festival. Prominent among them were Michael Eagan, Phillip Silver, Christina Poddubiuk and Debra Hanson.

Stratford's influence was felt beyond Canada. Tyrone GUTHRIE's demonstration of the effectiveness of the thrust stage was widely imitated at theatres both nationally and internationally. A style of design consisting of carefully lit and detailed costumes and properties on an elaborate scale against a plain background offered an exciting alternative to proscenium-arch settings.

By the 1970s, theatrical design was an established profession in Canada. The Associated Designers of Canada, founded in 1965, was mandated to improve working conditions for designers, promote professional and public recognition of these artists, and increase general communication between the designers. Towards this end, the association regulates professional contracts with PACT (Professional Association of Canadian Theatres) and provides exposure for design both nationally and internationally at a variety of exhibitions and competitions. Its members work in theatre, opera, dance, television and film, and teach at colleges and universities.

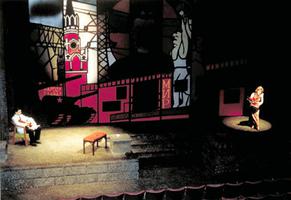

Simultaneously, many of the larger regional and festival theatres, though not exclusively these, instituted the principle of hiring a resident or head designer responsible for whole seasons of design rather than single productions. This was significant in that it allowed designers a certain economic stability and the opportunity to experiment and work together with a team of individuals (directors, technicians, craftspeople) over an extended period of time. The practice led to many fruitful director/designer collaborations, most noteworthy among these that of Cameron PORTEOUS and Christopher Newton. Their partnership at the VANCOUVER PLAYHOUSE and the SHAW FESTIVAL has spanned a period of over 20 years and resulted in many critical and popular successes. Cyrano de Bergerac (1982-3) and Cavalcade (1985-6 and 1995) are only two examples.

Other outstanding practitioners of that generation include Murray Laufer, whose architectural settings established the house style of the St Lawrence Centre in Toronto; Suzanne Mess, prominent as a costume designer for grand opera in North America; François BARBEAU, pre-eminent in Montréal; Philip Silver, the pioneer designer at the CITADEL THEATRE in Edmonton; and Jack King, whose designs for new Canadian works with the NATIONAL BALLET have been notable.

In the late 1960s and the 1970s, alternative theatres (eg. Tamahnous in Vancouver; TARRAGON THEATRE, Toronto Workshop Productions and THEATRE PASSE MURAILLE in Toronto), spurred on by nationalist sentiments, began to spring up across the country and, alongside the established festival theatres and growing regionals, offered a second source of employment for designers. With limited funds and a mandate to experiment with content and style, these theatres provided designers with a new set of challenges. Two of the most innovative designers who have worked for these theatres are Astrid JANSON and Jim Plaxton. Both have shown an extraordinary versatility and ingenuity in their use of materials, and an ability to exploit non-traditional spatial configurations.

Nationwide, there are now more than 60 schools, in addition to the National Theatre School, offering training for the theatre, and over 100 professional companies producing plays. Designers are no longer restricted to individual productions but are actively involved with architects in the design of new buildings and restoration of old structures. Canada is recognized for the ingenuity with which its architectural and theatrical designers transformed 19th-century industrial and public buildings for use in the 20th century and beyond.

By the early 1980s, Canadian designers had established a strong presence at the Prague Quadrennial, the international juried exhibition of the best in theatrical design and architecture from around the world. In 1975, the first submission by Canadian artists won Honourable Mention for designers Murray Laufer and François Barbeau; the 1979 presentation won special merit for excellence; and designer Roy Robitschek was singled out for "special mention" in 1983. Artists such as Michael LEVINE, who gained notoriety through his provocative collaborations with director Robert LEPAGE (Techtonic Plates 1988, Bluebeard's Castle and Erwartung 1993-95) and who designs for many of the world's leading theatres, opera houses and film companies, continue to affirm this country's international reputation for excellence.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom