Archaeologists and natural historians have long been fascinated by shell middens because of their great potential to enhance information about human adaptations and cultures. Early studies focused on the Mesolithic køkkenmøddinger ("kitchen middens") of northern Europe, but similar studies were conducted in Canada by the late 19th century. The English term midden is derived from a Scandinavian root referring to a trash heap composed of domestic refuse and located near a dwelling.

Archaeologists and natural historians have long been fascinated by shell middens because of their great potential to enhance information about human adaptations and cultures. Early studies focused on the Mesolithic køkkenmøddinger ("kitchen middens") of northern Europe, but similar studies were conducted in Canada by the late 19th century. The English term midden is derived from a Scandinavian root referring to a trash heap composed of domestic refuse and located near a dwelling.

The term shell midden refers to such a heap composed predominantly (50% or more) of the shells of MOLLUSCS and/or other shell-bearing animals such as ECHINODERMS and ARTHROPODS. The term shell midden was once commonly used to designate an archaeological site type but is now mostly employed to refer to a type of archaeological feature. Thus, shell middens are features that occur in some - but not all - shell-bearing archaeological sites, along with other types of deposits, such as natural soil layers, anthropogenically modified soils, dwelling floors (often the remains of houses constructed and occupied by the people who accumulated the shell middens), hearths, storage pits, mortuary features and so on. Archaeological sites containing shell middens present archaeologists with stratigraphic and ZOOARCHAEOLOGICAL puzzles that are intriguing, challenging and daunting.

Shell Midden Development and Occurrences

Shell middens develop where human populations - whether hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, agriculturalists or industrialists - harvest large quantities of shellfish, shuck out and process the meat for consumption and/or use the shells as raw materials, and leave large quantities of shell debris on their habitation and processing sites. Shell middens are a world-wide archaeological phenomenon, most frequently found on sites adjacent to marine shorelines and composed of marine shellfish remains (see SEASHELL), although shell middens composed of the remains of freshwater molluscs also occur in interior riverine locations in many places.

Once thought of as a hallmark of the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, following the end of the last glaciation (10 000-12 000 years ago), shell middens are now known to date from early in the Upper Palaeolithic (ca. 160 000 years ago) through to recent times. The earliest known shell middens have been found in South African near-shore caves and were accumulated contemporaneous to the emergence of anatomically and behaviourally modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) from archaic hominin populations.

Shell Middens in Canada

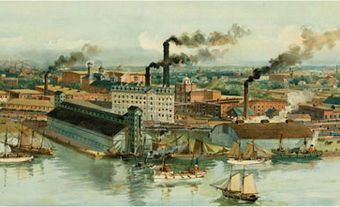

In Canada, prehistoric (pre-contact) shell middens occur most frequently in sites on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, and were accumulated by Native American hunter-gatherers adapted to high-productivity littoral ecosystems. Along the Pacific coast of British Columbia and adjacent areas, sea levels stabilized 5000-6000 years ago, extensive intertidal shellfish populations developed and were exploited by dense, sedentary human populations. As a result, very large archaeological sites composed of shell middens and house floors, sometimes several meters in depth, are common in the archaeological record dating from 5000 years ago to the historic period. Examples include the Marpole Midden (also known as the Great Fraser Midden), the Glenrose Cannery site and the St. Mungo Cannery site on British Columbia's lower mainland, the Namu site on the central coast, and, to the north, the Boardwalk site at Prince Rupert Harbour. Some of British Columbia shell-bearing sites are stratified over earlier archaeological deposits; for example, the Namu site contains cultural material dating as early as 10 000 years ago.

On the Atlantic coast, shell middens occur mainly on the shores of the Maritime Provinces, where sea levels have continued to rise, often rapidly, up to the present. As a result, shell middens are rarely preserved from earlier than ca. 2000 years ago, and many such sites, even from recent times, probably have been completely destroyed. Sites containing shell middens are relatively small and usually less than one meter in depth, perhaps because, in the Maritimes, Native peoples lived in smaller groups and were less sedentary than their counterparts on the west coast. Clusters of shell-bearing sites have been found at Port Joli Harbour on the South Shore of Nova Scotia and in the Quoddy Region in southern New Brunswick. The Port Joli sites are unusual in that they are located away from modern shorelines and are not actively eroding. In contrast, all of the shell-bearing sites in the Quoddy Region have been subject to coastal erosion. The best known of these is the Minister's Island site near St. Andrews; however, the best preserved is the Weir site on the Bliss Islands.

Middens dominated by freshwater mollusc shells are relatively rare in Canada, as compared to further south where extensive freshwater shell middens exist in the central and southeastern United States. However, a few freshwater shell-bearing sites have been reported from interior British Columbia, the southern prairies and southern Ontario. The most extensive of these is the MUSSEL shell midden associated with the SERPENT MOUND site at Rice Lake, Ontario, dating about 2000 years ago.

Archaeological Significance of Shell Middens

Studies of shell middens contribute to the development of archaeological history in Canada in five main ways. First, when past people accumulated shell middens, they produced stratified archaeological sites, and enhanced cultural component separation, in contexts where these phenomena would otherwise be unlikely to develop. Second, shell middens allow and enhance the preservation of a variety of organic materials (shell, bone and charcoal) amenable to radiocarbon dating. Together, these two factors enable archaeologists to construct more fine-grained and firmly dated culture-historical sequences than would otherwise be possible.

Third, calcium carbonates from the shells cause shell middens to be depositional environments that preserve organic remains - for example, the bones of animals used as food, tools and artistic/ornamental objects made from bones, teeth, antlers and shells, and human skeletal remains - infrequently preserved in the generally acidic soils characteristic of much of Canada. These finds allow for more detailed understandings of past technologies, lifeways and symbolic/spiritual behaviours. Fourth, and closely related to the previous point, applications of quantitative zooarchaeological, growth increment and stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic analyses to organic remains from shell middens enable archaeologists to construct more complete understandings of the human ecology of past populations - palaeodiets, subsistence practices, seasonal rounds and settlement patterns. Finally, the bones of extinct species, and species whose geographical ranges have fluctuated through time, are frequently preserved in shell middens; these finds contribute to understandings of biogeographic change. In addition, techniques such as sclerochronology (the study of physical and chemical variations in accretionary hard tissues) and oxygen isotope analysis are being applied to shellfish remains from shell middens in studies of prehistoric human ecology and long-term climatic and environmental changes.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom