Peoples and Territory

Linguistically-related groups of Central Coast Salish peoples include the Klallum, Halkomelem, Squamish, Nooksack (in Washington state) and Northern Straits Salish, sometimes referred to as Straits Salish (in British Columbia and Washington state). (See also Coast Salish, Northern Straits Salish and Interior Salish.)

Central Coast Salish peoples have historically occupied adjoining territories in and adjacent to the Lower Fraser Valley, on southeast Vancouver Island, around the southern Strait of Georgia and on intervening San Juan and Gulf Islands. (See also Indigenous Territory.)

Traditional Life

Central Coast Salish peoples often lived in large shed-roofed houses, sometimes referred to as plank houses. The houses were built in villages, from which trips were made to gather seasonal resources. Plank houses were often made of cedar wood. (See also Architectural History: Indigenous Peoples.)

Annual runs of salmon were essential to the diet and lifeways of many Central Coast Salish peoples. The Halkomelem fished with dip nets and large trawl nets towed between canoes. The Northern Straits Salish perfected the reef net, a unique fishing trap set between pairs of canoes. Most salmon were caught in summer when surplus quantities could be dried on open-air racks. While equipment has changed, Central Coast Salish peoples continue to fish in these areas.

Society

Life centered around household groups consisting of extended families whose lineages were traced through male or female lines of descent. Marriage with blood kin was not permitted and spouses usually came from different villages. Networks of kinship linked people throughout Central Coast Salish territory. Resource sites and ritual privileges were owned by lineages or kin groups, whose members worked under the direction of esteemed leaders.

There was a complex hierarchical class structure within the clans as well as slaves. People strove to maintain class standing by hard work, selective marriages and proper behaviour. Potlatches were most often held in summer and autumn, when people from neighbouring villages were invited to feast and recognize the hosts’ social position. Today, people are still linked by a network of kin and many continue to host potlatches.

Culture

Central Coast Salish culture is rich and diverse. Each nation has its own particular ceremonies, belief systems and oral histories. However, many Central Coast Salish nations have strong bonds of kinship as well as linguistic and cultural connections.

Like other Northwest Coast Indigenous peoples, the Central Coast Salish are well known for their art. House posts and design motifs featuring Northwest Coast animals and spiritual beings are prominent in their art works. (See also Northwest Coast Indigenous Art.)

Religion and Spirituality

Religious activity focused on spiritual helpers (sometimes known as guardian spirits) who conferred personal powers for hunting, doctoring and other endeavours. These spirts often took the form of animals, though they could also appear as monsters. Shamans had special connections to these spirits and learned how to communicate with them. Spirit dances, performed during winter rituals, celebrated these individual powers, and took the form of hereditary cleansing rituals, performed with masks, effigies or decorated rattles. Following a decline, participation in winter dancing has grown significantly since the 1970s.

Many Central Coast Salish people belong to Christian churches. The Indian Shaker Church (unrelated to the United States-based Shakers religion) developed in the late 19th century and contains features of both Christianity and Coast Salish spiritual tradition. Despite great cultural changes, distinctive rituals and religious expressions survive, uniting the small, dispersed villages and permitting the maintenance of a vigorous sense of Indigenous identity.

Creation Stories

According to Central Coast Salish legends, their ancestors were powerful, shape-shifting creatures. They could take human and non-human form, and could travel to the sky world and even the land of the dead. The world we know it as today was created when Xexá:ls, also known as the Transformer siblings, used their special powers to alter the world and its creatures. The siblings transformed some of the ancestors into the animals, plants and stones we recognize today. This is just one of the many origin stories that vary among Indigenous nations throughout the Central Coast Salish region and across the Northwest Coast.

Language

Central Coast Salish languages are part of the Salishan linguistic family. With few fluent speakers, some of these languages are considered endangered. Federal programs and policies aimed at assimilation, such as residential schools, eroded, and even eradicated, various Indigenous languages. Revitalization programs, such as those at local universities, colleges and high schools, attempt to record and promote these Indigenous languages as much as possible.

Contact with Europeans

The early maritime fur trade, which concentrated on the outer coast, did not directly affect Central Coast Salish peoples, whose territory was first explored by Spanish and British ships in the 18th century. In 1827, the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Langley in Halkomelem territory. In the late 19th century, as settlers were attracted to south Vancouver Island and the Fraser Valley, Central Coast Salish peoples were displaced and their population declined.

Contemporary Life

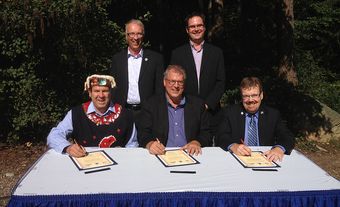

Central Coast Salish people in Canada have acted to protect their legal rights and title to their territory and its resources. Many bands have united into tribal councils to jointly seek legal and political remedies to their claims to share in the wealth of the natural resources, particularly the fisheries. Central Coast Salish nations also seek self-government. In 2009, the Tsawwassen First Nation treaty with Canada took effect, giving the Tsawwassen Coast Salish nation rights for self-governance within the Canadian constitution.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom