One of the most influential commissions in Canadian history, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963–69) brought about sweeping changes to federal and provincial language policy. The commission was a response to the growing unrest among French Canadians in Quebec, who called for the protection of their language and culture, and opportunities to participate fully in political and economic decision making. The commission's findings led to changes in French education across the country, and the creation of the federal department of multiculturalism and the Official Languages Act.

Origins of the Commission

Quiet RevolutionThe late 1950s to the 1970s represented a time of intense social, political, economic and cultural change in Quebec. It became known as the Quiet Revolution.

The death of Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis in 1959 was followed by the election of a Liberal government under Jean Lesage in 1960. This marked the end of the long reign of social and political conservativism and clerico-nationalism (see Lionel-Aldolph Groulx) under Duplessis’ Union nationale party, which had held power in the province since 1935 (except for the years 1940-44).

The Quiet Revolution was a period characterized by the rise of francophone nationalism, rapid modernization, sweeping secularization (meaning separation of church and state), and a push back against anglophone dominance in political and economic spheres.

Francophone Nationalism in QuebecBy the mid to late 1950s, some francophone intellectuals had already begun questioning the socio-economic inferiority of French Canadians in Quebec in relation to the anglophone minority who dominated the financial, commercial and industrial sectors of the economy. There was also a sense that Quebec was behind the times of other western societies and needed to catch up.

This new intellectual class favoured an urban, secular, democratic and modern francophone society.They wanted to see control over health, education and social services passed from the church to the state, and the development of a professional (rather than patronage-driven) civil service (see also Francophone-Anglophone Relations, French-Canadian Nationalism and Francophone Nationalism in Quebec).

There was some pressure from within the House of Commons, as well. For example, in the 1962 federal election, the Quebec wing of the national Social Credit Party, the Créditistes led by Réal Caouette, captured 26 seats and 26 per cent of the popular vote in Quebec. During its early years in Ottawa, the Créditistes supported the expansion of the French language in the federal Parliament and public service and flirted briefly with the idea of "special status" for Quebec.

The Donald Gordon AffairIn November of 1962, Donald Gordon, president of the Canadian National Railway (CN), was asked by a federal parliamentary committee on railroads to explain why there were no francophones among the 17 vice-presidents of the Crown corporation. At the time, CN was based in Montreal. Gordon responded that French-Canadians did not have the necessary competencies to hold upper management positions at CN.

His statements were received with anger and protests in Quebec. Students at the Université de Montréal, led by student union President (and future Parti-Québécois leader and Quebec premier) Bernard Landry, demonstrated in front of CN headquarters at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel and burned Donald Gordon in effigy.

Referencing the Gordon affair, a royal commission to examine Quebec's dissatisfaction with its place in Canada was first suggested by the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Le Devoir, André Laurendeau.

Spurred by the Gordon affair but also in response to the overall Quiet Revolution in Quebec, Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson created the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism in 1963. Pearson had a sense that Canada was on the verge of a national-unity crisis that would play out along linguistic lines. While some francophone nationalists wanted greater powers and autonomy for Quebec within Canada, others were advocating for Quebec’s separation from Canada, arguing that a separate state was the only way for francophones to truly achieve their ambitions and empowerment. Pearson was convinced that federal policies with respect to Quebec and the French language in Canada needed to change in order to avoid a national crisis.

Laurendeau and Dunton

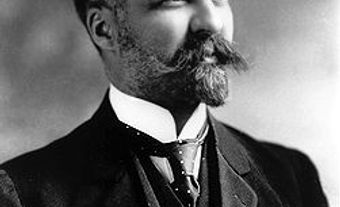

Laurendeau and A. Davidson Dunton, a prominent educator and journalist, were appointed co-chairmen of the commission. It became known as the B&B Commission or the Laurendeau-Dunton Commission. Laurendeau died in 1968 and his post was assumed by Jean-Louis Gagnon. Dunton, who was regarded as a visionary and humanitarian, was the first full-time Chairman of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and President of Carleton University.

Ten commissioners representing Canada's cultural-linguistic composition were chosen. All spoke English and French and commission business was conducted in both languages. Since education is a provincial responsibility, the co-chairmen called on all provincial premiers for their co-operation.

Scope of the Commission

The commission was charged with three main areas of inquiry: the extent of bilingualism in the federal government, the role of public and private organizations in promoting better cultural relations, and the opportunities for Canadians to become bilingual in English and French. The commissioners used the concept of "equal partnership" as their guiding principle, i.e., equal opportunity for francophones and anglophones to participate in the institutions affecting their lives.

At first, the Commission was limited by its mandate to explore issues relating to the languages and cultures of the English and French-speaking “founding peoples” of Canada. However, objections were raised early in the hearings by some of Canada’s largest ethno-cultural groups who disagreed with the basic premise of an officially bilingual and officially bicultural country. This prompted an expansion of the Commission’s focus. The commissioners were asked to report on the cultural contribution of other ethnic groups and how to preserve this.

In 1965, the Commissioners released a Preliminary Report that asserted their belief that the country was passing through a national crisis. They affirmed their belief in taking a ‘two founding peoples’ approach to managing social and linguistic tensions in Canada. The commission pushed forward with the idea that English and French alone should be recognized as official languages. The notion of official biculturalism, however, was abandoned.

In addition to a preliminary report (1965), a final report in six books was published, separately titled The Official Languages (1967), Education (1968),The Work World (Socioeconomic Status, the Federal Administration, the Private Sector, 1969),The Cultural Contribution of the Other Ethnic Groups (1969), The Federal Capital (1970), and Voluntary Associations (1970).

Passage of the Official Languages Act

Following the release of the final Commission report in 1969, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Trudeau passed Canada’s Official Languages Act. This legally established the requirement of the federal government to serve Canadians in either English or French. It was hoped that the policy of official bilingualism would improve career prospects for francophones in federal institutions and the private sector, assure that French Canadians could receive services from the federal government in their own language anywhere in Canada, and challenge the nationalist claim that Quebec required special powers or a separate state to protect the French language and culture.

Multiculturalism within a Bilingual Framework

Two years later, in 1971, Canada’s multiculturalism policy was adopted by Pierre Trudeau’s government. An unexpected byproduct of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, multiculturalism was intended as a solution to manage both francophone nationalism and increasing cultural diversity. The policy acknowledged that Canadians come from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds, and that all these cultures have intrinsic value. In a speech in the House of Commons in April of 1971, Trudeau introduced it as “a policy of multiculturalism within a bilingual framework,” or a policy that would complement the Official Languages Act by facilitating the integration of new Canadians into one or both of the official-language communities. “Although there are two official languages, there is no official culture,” said Trudeau.

Controversy

For many francophone Quebecois, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism was a move to obscure the political issues. For many anglophones, especially in Western Canada, it was an attempt to force the French language on an unwilling population. However, the commission revealed that francophones were not well represented in the economy or in the decision-making ranks of government, that educational opportunities for francophone minorities outside Quebec were not equal with those provided for the anglophone minority within Quebec, and that French-speaking Canadians around the country could neither find employment nor be served adequately in their language in federal government agencies.

Changes Following the Commission

Recommendations to correct these and other weaknesses were implemented with unusual speed. Educational authorities in all nine anglophone provinces reformed regulations concerning French minority education and moved to improve the teaching of French as a second language with financial assistance from the federal government. New Brunswick declared itself officially bilingual; Ontario did not, but greatly extended its services in French. French-language rights in the legislature and courts of Manitoba — disallowed by statutes passed in Manitoba in 1890 — were restored by a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in 1979.

A federal department of multiculturalism was established. Institutional bilingualism at the federal level became a fact with the passing of the Official Languages Act(1969) and with the appointment of a Commissioner of Official Languages. Because of lack of time, the commission did not examine constitutional questions, as anticipated in the introduction to the final report, and the movement toward independence in Quebec continued. The commission did, however, lay the foundation for functional bilingualism throughout the country, and for increased acceptance of cultural diversity (see also Official Languages Act (1988)).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom