In 1841, Britain united the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada. This was in response to the violent rebellions of 1837–38. The Durham Report (1839) recommended the guidelines to create the new colony with the Act of Union. The Province of Canada was made up of Canada West (formerly Upper Canada) and Canada East (formerly Lower Canada). The two regions were governed jointly until the Province was dissolved to make way for Confederation in 1867. Canada West then became Ontario and Canada East became Quebec. The Province of Canada was a 26-year experiment in anglophone-francophone political cooperation. During this time, responsible government came to British North America and expanded trade and commerce brought wealth to the region. Leaders such as Sir John A. Macdonald, Sir George-Étienne Cartier and George Brown emerged and Confederation was born.

(This is the full-length entry about the Province of Canada. For a plain language summary, please see Province of Canada (Plain Language Summary).)

Durham Report

Following the violent rebellions of 1837–38 in Upper and Lower Canada, Lord Durham was sent to the colonies in 1838 to determine the causes of unrest. The solution he recommended in the Durham Report (1839) was to unify Upper and Lower Canada under one government.

Lord Durham proposed a united province to develop a common commercial system. A combined Canada would also have an overall English-speaking majority. This would help control the divisive forces Durham saw in the mostly French Lower Canada. It would also make it easier to introduce responsible government, which he advocated. Britain agreed to the union, but not to responsible government.

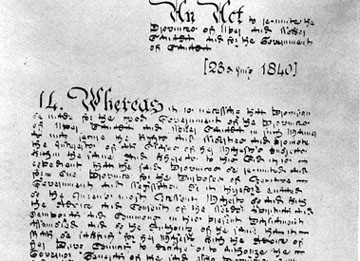

Act of Union

Durham recommended basing representation on population. (See also: Rep by Pop.) The Act of Union, however, gave Canada East and Canada West the same number of seats in the new Legislature. This occurred even though the population of English-speaking Canada West (480,000) was considerably smaller than the overall population of Canada East (670,000), of whom about 510,000 were French Canadians. The French population would therefore be under-represented from the start.

Yet giving each province equal representation had an unforeseen result. The two Canadas, each with its separate history, society and culture, remained equal, distinct sections inside one political framework. They were now Canada West and Canada East, but the names Upper and Lower Canada survived in popular and official use. The Union Act had embedded dualism in the very constitution. It resulted in dual parties, double ministries and sectional politics. (See also: Act of Union: Timeline; Act of Union: Editorial.)

In 1840, the British Parliament passed the Act of Union. It went into effect on 10 February 1841. The Act established a single government and legislature in a united Province of Canada. The capital was located in Kingston from 1841 until 1844. It was then moved to Montreal until 1849. It was located in Toronto from 1849 to 1851, in Quebec City from 1851 to 1855, in Toronto again from 1855 to 1859, and once more in Quebec City from 1859 to 1865. It was held in Ottawa from 1866 to 1867, when the city became the capital of the Dominion of Canada under Confederation.

Push for Responsible Government

French Canadians realized that the purpose of unifying the colonial government was to try and assimilate them into English Canadian society. But a rising liberal leader, Louis LaFontaine, saw the advantage of allying with Canada West Reformers to seek responsible government. LaFontaine believed that responsible government would allow French Canadians to share in ruling the Province. They could maintain themselves as a people while co-operating with Anglo-Canadian allies. LaFontaine readily responded to overtures from leading Canada West Reformers Francis Hincks and Robert Baldwin. (See also: The Politics of Cultural Accommodation: Baldwin, LaFontaine and Responsible Government.)

Hincks, a Toronto journalist and a shrewd strategist, was already backing Baldwin's campaign for responsible rule. It centered on the British principle of responsible government. Its adoption in Canada would mean that governments would depend on elected parliamentary majorities and not on a colonial governor or an appointed council. Baldwin and LaFontaine built up a powerful Reform alliance based on this principle. In September 1842, they had won enough support in parliament to compel Governor General Sir Charles Bagot to reconstruct his ministry. (At that time, governors controlled the executive branch of the colonial government and formed cabinets.)

A shift in imperial policy finally brought an acceptance of responsible government to the colonies of Canada and Nova Scotia. (See also: Nova Scotia: The Cradle of Parliamentary Democracy.) In 1846, Britain's repeal of the corn laws signalled a movement towards free trade. This ended a centuries-old pattern of imperial trade controls and protective duties. Britain no longer saw the need to withhold internal self-government from its more politically advanced colonies (as opposed to lesser-developed ones such as South Africa, which did not get responsible government until 1872). In 1847, Lord Elgin came to Canada as governor general to implement responsible government. (See also: Responsible Government: Collection.)

Reformers swept elections in both Canadas in early 1848. When Henry Sherwood's Tory-Conservative ministry resigned, Elgin called on Reformers to form a government. Responsible rule was confirmed in March and an all-Reform Cabinet took office. LaFontaine, who had the larger following, was premier. Baldwin was co-premier.

1840s: Tough Times and a Severe Test

There was still a severe test to come. Trade was at a low ebb and the newly built St. Lawrence River canals were half used. Tory merchants in Montreal blamed the problem on the loss of imperial tariff protection. The spread of worldwide economic depression since 1847 was a deeper cause. In the early 1840s, farming, forestry and canal building expanded, while growing towns absorbed a surge in British immigration. But by the late 1840s, times were hard. Frontier expansion was blocked by the Precambrian Shield and a new tide of Irish immigrants poured into Canada. They were destitute and typhus-infected and fleeing famine in their homeland.

Amid these strains, the Reform ministry brought in the 1849 Rebellion Losses Bill. It was meant to compensate damages suffered in the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837. (Upper Canadians had already settled their claims.) For French Canadians, the bill was a form of social justice. It was also proof that responsible government could work for them. Canada East's English-speaking Tories, however, saw it as a rewarding of rebels. The Reform-dominated legislature, meeting in Montreal, passed the bill over heated protests. Tory-Conservatives looked to the British governor Lord Elgin to refuse his assent, but he did not. After all, the measure had been recommended by a responsible ministry with support of the parliamentary majority.

All the strains over this issue burst forth in the Montreal Riots. Elgin and his ministers rode out the storm, which subsided after a few wild days in April. Then in October, the Annexation Association manifesto appeared in the city, urging union with the United States. It proved only a bitter, passing gesture. Most French Canadians felt colonial self-rule was working. Eastern Tories drew back. Meanwhile, Reformers and Conservatives in Canada West held firm to British connections. Responsible government survived its first test.

Railway and Trade Booms

By 1850, depression had given way to an era of rapidly expanding world trade. Grain and timber production rose. The St. Lawrence canals were bustling. Montreal merchants soon forgot about annexation. With more British and American capital available, Canadian entrepreneurs took eagerly to railway building. Tracks linked Montreal to ice-free Portland, Maine, and Toronto to the Upper Great Lakes at Collingwood. A line from Niagara Falls to Windsor, via Hamilton, tied in with rails to New York at one end and Chicago at the other. It soon extended to Toronto as well. The Grand Trunk Railway, incorporated in 1852, built a trans-provincial route connecting Quebec City, Montreal and Toronto to Sarnia, Ontario.

However, this first great railway boom subsided after 1857 in another worldwide depression. The Grand Trunk, over-promoted and extravagantly built, was saddled with debt and political scandals. Nevertheless, rail lines had remade Canada. They broke inland winter isolation, vastly improved long-range transport, and focused development on major towns. Railway-connected factory industries grew. Montreal, Toronto and Hamilton rapidly advanced in size, wealth and complexity.

The 1854 Reciprocity Treaty (free trade) with the US stimulated growth. It gave Canadian grain and lumber free access to American markets. It also tied Canada far more closely to the American economy. The US Congress’ decision in 1865 not to renew reciprocity led Canada to seek economic integration with other British North American provinces.

However, the rise in provincial industry in the 1850s also brought a Canadian protective tariff. In 1858 and 1859, duties were raised enough to shelter manufacturers effectively. This protection was incidental to the need for revenue, which was made urgent by the heavy public debt incurred by railway grants. Duties were lowered again in 1866. Still, the tariff of 1858–59 foreshadowed the tariff-friendly National Policy. It also signified the increasingly close ties between government and business in an era of advancing capitalism.

Growing East-West Rift

Since the early 1850s, certain factors had been disrupting the Province’s political life. Left-wing Reform elements emerged around 1850. The Parti Rouge in Canada East and the Clear Grits in Canada West called for fully elective democracy and an American-style written constitution. In 1851, Baldwin and LaFontaine gave up fighting radicalism in their own ranks and left politics. Their chief lieutenants, Francis Hincks and Augustin Morin, took over the ministry. At first, it looked more secure. Radicalism waned in an atmosphere of widespread enthusiasm for railway promotion.

But soon, public education and church-and-state relations became divisive issues. Protestants in Canada West widely believed in non-denominational public schools. They also rejected state-connected and state-supported religion. In Canada East, however, mainstream French Catholics Liberals had close ties with the Catholic hierarchy. They widely upheld denominational schools and church-state ties. French Canadians backed bills in Parliament to enlarge the rights of state-aided Catholic schools in Canada West.

Many Upper Canadians (as many in Canada West still called themselves) came to feel that their interests were being thwarted by unchecked French Catholic power. The census of 1851–52 also revealed that Canada West had the greater population. It was now underrepresented politically, while paying the larger share of taxes.

George Brown, the editor of the powerful Toronto Globe, entered the Legislative Assembly as a Reform independent. He called for “justice” for Canada West. In 1853, he proposed representation by population to give the western region its full weight in seats. His initial attempt got nowhere, but it began a struggle over “Rep by Pop.” Those in Canada West fought for it to overcome “French domination.” French Canadians fought against it to keep from being being submerged in the Union once again.

Macdonald and Cartier Emerge

On 22 June 1854, the Hincks-Morin ministry fell. The old Reform alliance had crumbled under sectional strains. In its place, a new ruling Liberal-Conservative coalition appeared. It combined the moderate Liberals of Hincks and Morin with prominent Tory-Conservative members. In particular, a politician from Kingston named John A. Macdonald was rapidly gaining stature. This broad coalition managed to abolish both the old Clergy Reserves and the Seigneurial System. Clear Grits and Rouges, left in the cold, called the Conservative-oriented combination “unprincipled.”

Actually, the coalition rested on areas of agreement between the major parties: the development of railways and businesses, maintenance of the Union, and defence of the French Canadian presence within it. The coalition was led by the easygoing but resourceful John A. Macdonald and George-Etienne Cartier, a party manager and Montreal lawyer for the Grand Trunk Railway. Under them, the Conservative Party of the future took shape.

On the other side of the aisle, Brown and the Clear Grits, earlier adversaries, moved together. On 8 January 1857, a rebirth of Upper Canadian Reform was made at a party convention in Toronto. Brownites, Grits and some returning moderate Liberals adopted a platform calling for rep by pop, secular education and the acquisition of Rupert's Land. The vast wilderness to the north was of interest to Toronto’s businessmen, who were keen to expand their trade domain, and to farmers eager for new land. The resulting Brownite-Grit party powerfully consolidated Canada West sectionalism. Its emphasis on farmers’ rights and its hostility to big railway interests and expensive government also had a long political future.

Wider BNA Union Urged

A non-stop struggle ensued between Macdonald-Cartier conservatism and Brownite liberalism, loosely allied with the limited Rouge eastern group under A.A. Dorion. In August 1858, a Brown-Dorion government lasted just two days. (See also: Double Shuffle.) The returning Conservatives now called for the union of British North America as the answer to Canada’s troubles. They were urged on by Alexander Galt, a leading Montreal financier, who joined the ministry. But the other provinces were uninterested and federation was set aside.

At another Reform convention in November 1859, Brown moved his Grits behind a dual federation of the Canadas (already suggested by Dorion). This motion quickly failed in the Legislature. While both sides had now adopted the federal principle as a way out of sectional disruption, neither was actually ready for it. Fights over rep by pop returned.

In May 1862, the Macdonald-Cartier forces were defeated on a costly Militia Bill, a response to border tensions roused by the American Civil War. Sandfield Macdonald, a moderate Reformer, tried to keep the union running by double majority. This required majorities for government measures from both halves of the province. Sandfield's principle failed. He hung on until early 1864, when John A. Macdonald returned, only to be defeated. Elections and government shifts had achieved nothing in the equal balance of sectional forces. By June 1864, with the Province deadlocked, Brown made a crucial offer to back a government willing to remake the Union.

Confederation, Quebec and Ontario

Negotiations between John A. Macdonald, Cartier, Galt and Brown quickly led to an agreement to seek general federation. It would include the North-West, or a federation of the Canadas if that failed. The first aim did not fail. Brown and two Liberal colleagues joined the ministry, and the Great Coalition took up the federation cause with the other BNA colonies. The outcome was the scheme for Confederation and the British North America Act of 1867 (now the Constitution Act, 1867).

Throughout the shaping of the plan for Confederation, Canadian representatives had played commanding roles, especially John A. Macdonald. When it went into force on 1 July 1867, the day of the old Canadian union was over. It was scarcely mourned amid bright aspirations for the future. Before the union ended, its Legislature endorsed the federal scheme with both English and French majorities in 1865. In 1866, it drafted constitutions for the successor provinces of Quebec and Ontario. The united Province had gone through much and achieved much. But its final achievement lay in Confederation itself.

See also: Confederation: Collection; Confederation 1867: Editorial; Quebec and Confederation; Ontario and Confederation; Fathers of Confederation; Fathers of Confederation: Table; Mothers of Confederation: Editorial; George Brown: 1865 Speech in Favour of Confederation; Confederation’s Opponents.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom