The Persons Case (Edwards v. A.G. of Canada) was a constitutional ruling that established the right of women to be appointed to the Senate. The case was initiated by the Famous Five, a group of prominent women activists. In 1928, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that women were not “persons” according to the British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867). Therefore, they were ineligible for appointment to the Senate. However, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council reversed the Court’s decision on 18 October 1929. The Persons Case enabled women to work for change in both the House of Commons and the Senate. It also meant that women could no longer be denied rights based on a narrow interpretation of the law.

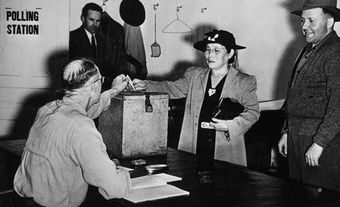

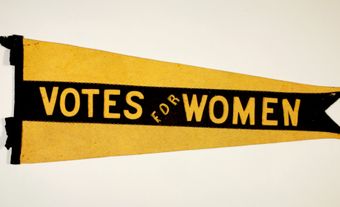

Women, the Vote and Political Office

By 1927, most Canadian women were able to vote in federal elections and in provincial elections (except in Quebec). Women first achieved the vote — and the right to hold political office — in Manitoba in January 1916. This was followed soon after by Saskatchewan (March 1916) and Alberta (April 1916). British Columbia and Ontario gave women the right to vote in April 1917. Nova Scotia followed suit in April 1918 and Prince Edward Island in May 1922. New Brunswick gave women the vote in April 1919; they gained the right to run for provincial office in March 1934. Only Quebec women could not vote in provincial elections in 1927; they had to wait until 1940 for that right. Newfoundland, which did not join Confederation until 1949, gave women the vote in April 1925. (See also Women’s Suffrage; Women’s Movements in Canada.)

Women of non-white backgrounds often encountered racial barriers to voting. Indigenous peoples – the Inuit, First Nations and Métis – gained the right to vote at different times in Canadian history. Federal election laws excluded the Inuit from voting until the 1950s. First Nations women did not receive the right to vote until 1960. The Métis could vote in federal and provincial elections if they met voter qualifications, such as age and ownership of property. (See also Indigenous Women and the Franchise.)

For Black Canadians, those who were citizens and owned taxable property could vote after the abolition of slavery. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.) However, since many Black Canadians lived in poverty because of slavery and systemic racism, few were eligible to vote. Additionally, by the mid-1800s, full citizenship was legally limited to white men and most colonies removed women’s franchise. In 1917, the Wartime Elections Act extended the right to vote to Black women related to Black servicemen. (See also Black Voting Rights in Canada.)

Most Canadians of Asian heritage were denied the right to vote in federal and provincial elections. Federally, the Electoral Franchise Act (1885) explicitly denied Chinese Canadians the right to vote. In 1898, new legislation extended the franchise to Asian voters. (See also Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians.)

In May 1918, the majority of Canadian women over the age of 21 became eligible to vote in federal elections. The following year, they received the right to run for office in the House of Commons. In 1921, Agnes Macphail became the first woman elected to the House of Commons. However, the Senate was still closed to women. This was because of the way the Canadian government interpreted Section 24 of the Constitution Act, 1867.

Persons in the BNA Act

The British North America Act (BNA Act) of 1867 — now known as the Constitution Act, 1867 — was the law that created and governed the Dominion of Canada. According to Section 24 of the Act, only “qualified persons” could be appointed to the Senate:

The governor general shall from time to time, in the Queen’s name, by instrument under the Great Seal of Canada, summon qualified persons to the Senate; and, subject to the provisions of this Act, every person so summoned shall become and be a member of the Senate and a senator.

To be a “qualified person,” one had to be at least 30 years of age, own property worth at least $4,000, and reside in the province of their appointment. But the Act did not specify whether “persons” included women or not. In 1867, “person” was legally understood to refer only to men. Consequently, the Canadian government had since that time interpreted “persons” in Section 24 as including men only.

The government held this position in 1922, when female activists in Alberta proposed Emily Murphy, Canada’s first woman judge, for a Senate position. Thousands across Canada (including the National Council of Women of Canada, the Federated Women’s Institutes and the Montreal Women’s Club) supported Murphy’s appointment. Many newspapers also championed her cause. Yet the government responded that even though it “would like nothing better than to have women in the Senate […] the British North America Act made no provision for women.” This was not the first time that Murphy had been discounted as a “person.” In 1916, on her first day as a judge, a lawyer challenged her on the basis that she was not a “person” and therefore not qualified to be a judge.

The Famous Five Petition

According to Canadian legal scholar Sheryl Hamilton, five different governments from 1917 to 1927 suggested that although they would like to appoint a woman to the Senate, Section 24 of the BNA Act made it impossible. In 1923, Prime Minister Mackenzie King asked Senator Archibald McCoig to propose an amendment to the Act; but the proposal was never made.

To activists, the government was using Section 24 of the BNA Act as an excuse for stalling. In August 1927, Emily Murphy invited four prominent women activists ( Nellie McClung, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards) to her home in Edmonton. Her plan was to send a petition to the Canadian government regarding the interpretation of the word “persons” in the BNA Act. According to Section 60 of the Supreme Court Act, a group of five persons could petition the government to direct the Supreme Court to interpret a point of law in the BNA Act. On 27 August 1927, the Famous Five signed the letter, which was sent to the governor general. The petition asked that the Supreme Court rule on the following two questions:

- Is power vested in the Governor-General in Council of Canada, or the Parliament of Canada, or either of them, to appoint a female to the Senate of Canada?

- Is it constitutionally possible for the Parliament of Canada under the provisions of the British North America Act, or otherwise, to make provision for the appointment of a female to the Senate of Canada?

The minister of Justice, Ernest Lapointe, believed that it would be an “act of justice to the women of Canada to obtain the opinion of the Supreme Court of Canada upon the point.” The Supreme Court was then directed to consider the following question: “Does the word ‘Person’ in section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867, include female persons?”

Supreme Court Decision

On 24 April 1928, the Supreme Court of Canada (Chief Justice Francis Alexander Anglin, Mr. Justice Lyman Duff, Mr. Justice Pierre-Basile Mignault, Mr. Justice John Lamont and Mr. Justice Robert Smith) ruled unanimously that women were not “persons” under Section 24 of the BNA Act. Women were therefore ineligible for appointment to the Senate.

Their decision was based on the premise that the BNA Act had to be interpreted the same way in 1928 as in 1867, when the Act was passed. It was generally accepted that in 1867, “persons” would have included men only. This was supported by the fact that women could not hold political office at that time. Therefore, the justices argued, the BNA Act would have specifically referred to women if they had intended an exception for Senate appointments.

Privy Council Decision

The Famous Five were disappointed, but not defeated. There was one higher authority to which they could appeal: the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, England. It was Canada’s highest court of appeal until 1949. After much deliberation, the Privy Council reversed the decision of the Supreme Court on 18 October 1929. It concluded that “the word ‘persons’ in sec. 24 does include women, and that women are eligible to be summoned to and become members of the Senate of Canada.”

Lord Sankey, who delivered the judgement on behalf of the Privy Council, also remarked that the “exclusion of women from all public offices is a relic of days more barbarous than ours […] and to those who ask why the word [persons] should include females, the obvious answer is why should it not.”

Furthermore, Sankey said:

their Lordships do not think it right to apply rigidly to Canada of to-day the decisions and the reasonings therefor which commended themselves […] to those who had to apply the law in different circumstances, in different centuries, to countries in different stages of development.

In 1867, Canadian women were unable by law to hold political office. However, the situation in 1929 was very different. Most women were able to vote and become candidates in all federal and provincial elections. (There were two exceptions: in Quebec, women did not have the vote; and in New Brunswick, women could vote, but could not hold political office.) The Privy Council judgment was therefore consistent with the legislative changes of the 1910s and 1920s concerning women’s suffrage.

Criticism of the Famous Five

The Famous Five of the Persons Case have been the subject of renewed controversy. While some see them as symbols of modernity and of women’s political rebellion and progress, others have criticized the group as racist and elitist. They feel that the Five’s accomplishments were tarnished by their associations with the eugenics movement; specifically, their support of laws that led to the forced sterilization of thousands of people, a disproportionate number of whom were Indigenous women. (See also Eugenics: Pseudo-Science Based on Crude Misconceptions of Heredity; Tommy Douglas and Eugenics; Sterilization of Indigenous Women in Canada.)

Significance

On 15 February 1930, Cairine Wilson was sworn in as Canada’s first female senator. The implications of the Persons Case, and of Wilson’s appointment, were far-reaching. First, the Judicial Committee’s decision meant that women had been legally recognized as “persons.” This meant that women could no longer be denied rights based on narrow interpretations of the law. Second, women could now continue to work for greater rights and opportunities through the Senate as well as the House of Commons. The Persons Case was a significant moment in the history of women’s rights, even though the struggle for equality continues almost 100 years later.

Since 1979, the Governor General’s Awards in Commemoration of the Persons Case have been awarded annually to five individuals who have advanced the equality of women and girls in Canada. In 1999, the Women are Persons! monument was unveiled at the Olympic Plaza in Calgary, Alberta. A similar monument was installed on Parliament Hill in Ottawa the following year. The statue is also featured on the $50 banknote that is part of the Royal Canadian Mint’s Canadian Journey Series.

See also Right To Vote; Voting Rights Collection; Women and the Law; Women’s Movements in Canada; Women’s Suffrage; Women’s Suffrage Timeline; Women’s Suffrage Collection; Indigenous Suffrage; Black Voting Rights in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom