Formed at the turn of the 19th century, the Parti canadien was an alliance of French Canadian deputies in the elected Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada (Québec). First led by Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, the party used the assembly as a forum to promote its authority in the colonial government. The Parti canadien was the first political party in Canadian history.

Following the War of 1812, and under the leadership of Louis-Joseph Papineau, the party fought for greater authority for the assembly, opposed the governor’s constant pressures for subsidies, and combatted plans to unite Upper and Lower Canada. In 1826, the party became known as the Parti patriote (see Patriotes).

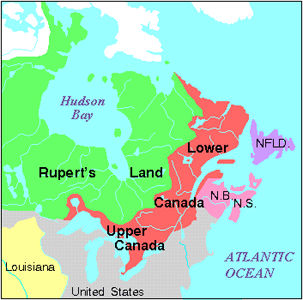

The Constitutional Act of 1791

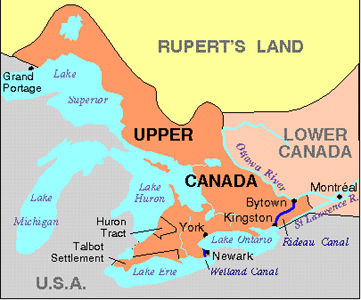

The Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the Province of Québec into two colonies: Upper and Lower Canada. In many ways, the act set the stage for the formation of the Parti canadien. Upper Canada, settled by thousands of Loyalists following the American Revolution, obtained English laws and institutions (see Common Law); Lower Canada, with its predominantly French Canadian population, retained its French civil laws and institutions (see Civil Law). More importantly, the act established elected legislative assemblies in both Canadas.

Colonists could now elect deputies to represent their region in the colonial parliament. Voting requirements were based on property: anyone with a property valued at over 40 shillings in the country, 5 pounds in the towns, or who paid an annual rent of 10 pounds could vote. Since land was more easily available in the colonies than in Britain, Canadians could vote in greater number. Though this assembly gave a voice to the people of the colony, it was a limited. Along with his appointed Executive and Legislative Councils, the Governor General had absolute authority over the colony. The councils were not accountable to the elected assemblies.

The Bédard Years — The First Political Party in Canada

There were no political parties at the turn of the 19th century, and alliances between deputies were fleeting and temporary (see Party System). However, deputies began to unite around linguistic and cultural roots, particularly, British and Canadien (French Canadian). The Parti canadien, which resulted from an alliance among French Canadian deputies,was initially a conservative group under the heavy influence of the conservative seigneurs (see Seigneurial System). However, as younger, more educated deputies from the liberal professions — doctors, lawyers and notaries — were elected, the party began to adopt a more liberal stance. Influenced by a wave of revolution in the late 18th century (e.g., in the United States, France and Haiti), these men had developed a political and national consciousness and wanted greater control over their colony (see Francophone Nationalism in Québec). Since 40 out of 50 seats were in rural regions, where the population was predominantly French Canadian, the party could count on a significant support.

The party rose to pre-eminence under the guidance Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, who was its uncontested leader from 1804 to 1812. Under his leadership, the Parti canadien became the very first political party in Canadian history. A lawyer by training, Bédard joined the Legislative Assembly in 1792 as the representative for Northumberland. Though he is not remembered for having an imposing presence or great oratory skill, Bédard was well versed in British constitutional law and his principles came to embody those of the Parti canadien. As the true representative of the people, he argued that the Legislative Assembly, not the governor’s appointed councils, should control the colonial Parliament. As such, he demanded that the assembly be given greater authority over budgetary matters and that the majority party in the Legislative Assembly, not the governor, select the Legislative Council. More importantly, Bédard argued for ministerial responsibility, meaning that the governor’s ministers should be accountable to the elected assembly. However, since the assembly lacked any real authority and could not impose new laws or alter the constitution, deputies used it as a forum to voice their grievances and demand greater authority.

In 1806, Bédard, François Blanchet, Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Joseph LeVasseur Borgia, Joseph Planté and others founded Le Canadien, a newspaper that became the voice of the Parti canadien. Created to counter The Quebec Mercury, the voice of the British elite and a vocal opponent of the Parti canadien, Le Canadien educated French Canadians on their constitutional rights, promoted the aims of the French Canadian majority in the assembly, and fought for the preservation of the French Canadian “nation.”

Opposition — The “English Party” and Governor James Craig

The Parti canadien faced serious opposition in the first decade of the 19th century. Its main adversary in the elected assembly was a group that historian Allan Greer called the “English party.” This party has also been labelled the “British” and “Tory” party. Though this group included some French Canadians, it was mostly an alliance of British merchants from Montréal and Québec City. However, because 80 per cent of seats were in predominantly French-speaking areas, the party was never a dominating force in the assembly. Instead, its influence was manifested in the governor’s appointed Legislative and Executive Councils where Tories promoted an agenda beneficial to their mercantile and political aims. This group was known as the Clique du Château.

Governor General Sir James Henry Craig (1807–11) also opposed the party. Described by some as a “reign of terror,” Craig’s tenure was decidedly anti–French Canadian: he sided with the British mercantile elite, opposed the Parti canadien, and sought to limit the influence of French Canadians in the colony. Craig suggested the creation of more “English counties” to increase British presence in the national assembly and the mass immigration of Britons and Americans to Lower Canada as a way to reduce French Canada’s influence. In 1810, frustrated with the Parti canadien’s opposition in the assembly, he had Bédard and other staff members from Le Canadien arrested and temporarily imprisoned. Needing a more conciliatory governor, Craig was recalled to England in 1811 (see also Francophone–Anglophone Relations).

The Papineau Years

In the wake of the costly War of 1812, the colonial government faced a significant deficit. Governor General Sir John Coape Sherbrooke took aim at the Legislative Assembly’s surplus funds, which it had accumulated over the years by raising taxes on such luxuries as salt, coffee, tobacco and sugar (see Taxation). In 1818, Sherbrooke demanded that the assembly allow subsidies to be taken from this surplus to pay for civil salaries and pensions. However, the Constitutional Act of 1791 specifically stated that the elected assembly controlled all allocations of tax revenue. By demanding that it allocate these subsidies without any conditions, Sherbrooke was undermining the constitutional authority of the assembly.

Over the next decade, the Parti canadien — led by Louis-Joseph Papineau — argued with the governor and his appointed councils over finances. The struggle persisted under the tenures of Sherbrooke (1816–18), the Duke of Richmond (1818–19) and the Earl of Dalhousie (1820–28). Every time the governor demanded that subsidies be allocated without condition, the deputies would instead stall and expose corruption in the government. (In one such instance, the deputies discovered that Attorney General Jonathan Sewell enjoyed four appointed positions, each with a generous salary.) In the following decades, the assembly used its control over taxation to pressure the government to grant it more authority.

In 1822, the party confronted a plan to unite Lower and Upper Canada. Unhappy with their current political situation and hoping to, among other things, assimilate French Canadians, a group of British merchants from Montréal, submitted a bill to the British Parliament pleading for the union of Upper and Lower Canada. The Parti canadien opposed this plan and in 1823 sent Papineau and John Neilson to London with a petition of over 60,000 names against union. Historians are still unsure about the actual impact of their visit, but whatever it may be, union was not accepted and the two returned to Canada as heroes. This was a great victory for the Parti canadien, further establishing the party as the voice and defender of the French Canadian nation.

From Canadien to Patriote

In 1826, members of the Parti canadien began calling themselves the Parti patriote. They were no longer fighting for a stronger assembly, but for the rights and existence of an entire nation. By adopting the title of patriote, they linked their party with other national-democratic movements of the period, such as the American and French Revolutions. In the 1830s, the party continued to use its powers over taxation to increase the Legislative Assembly’s authority in colonial government — first leading to a political stalemate and then to rebellion (see Rebellion in Lower Canada).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom