In strictly geographic terms, the North refers to the immense hinterland of Canada that lies beyond the narrow strip of the country in which most Canadians live and work, but generally refers to the Northwest Territories, the Yukon and Nunavut.

The North is a varied land with mighty rivers, forested plains, "great" lakes that extend from the Mackenzie Valley to the edge of the Canadian Shield, an inland sea (Hudson Bay), the beaches, bars and islands of the arctic coast and the arctic seas themselves, in winter covered by ice and snow, in summer by floating fields of ice. Immense flocks of birds migrate to the Arctic each summer; other wildlife includes whales, walrus, narwhal, seals, moose, muskoxen and caribou - the staple of the Indigenous peoples.

Natural History

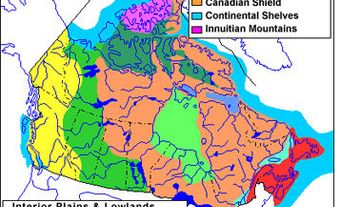

Biologists divide the North into 2 great regions called "biomes" comprising the Boreal Forest and the Tundra. The boreal forest, characterized by spruce trees and muskeg, is a broad band of coniferous forest extending across Canada from Newfoundland to Alaska. The tundra, which reaches from the boreal forest northward to the Arctic Ocean and comprises 20% of Canada's landmass, is treeless and is sometimes called "the barrens," although it includes landscapes as varied and beautiful as any in Canada - plains, mountains, hills, valleys, rivers, lakes and sea coasts.

The tundra and the boreal forest meet along the treeline, a transitional zone usually many kilometres wide. This very important biological boundary which separates forest and tundra also generally separates the traditional lands of the Dene and the Inuit. The treeline may also be viewed as the southern limit of the Arctic, the boundary between the Arctic and the Subarctic. Arctic or Subarctic, however, the region is one of great climatic contrasts. In midsummer it is never dark, but in midwinter the only daylight is twilight, a combined sunset and sunrise. In the very far north, the Sun does not appear above the horizon for many weeks.

Although summer can be pleasantly warm, with temperatures in excess of 20° C, the season is short and the weather often raw and damp. Both rainfall and snowfall are light. Because, in the true Arctic, precipitation is as low as that in the driest parts of the Canadian prairies, the Arctic may be described as semidesert. It is remarkable, therefore, that the land surface in summer is predominantly wet and swampy and dotted with innumerable shallow ponds, fens and water-filled frost cracks.

In southern Canada the ground freezes in the winter, but downward from the surface, and thaws completely again in the spring. In the subarctic and arctic regions, frost has penetrated below the maximum depth of summer thaw and a layer of frozen ground called permafrost remains permanently beneath the surface. The seasonally thawed active layer of the soil holds water like a sponge from rain and melting snow which cannot drain through the frozen ground.

The combination of climate and topography in the northern biomes has produced unique plant and animal populations. The species that thrive in the North are tough in order to survive, but they are also vulnerable. Because of the fragility of this region, it would not be difficult to cause irreparable injury to the environment and to the peoples who depend upon it.

Peoples of the North

It is not always easy to remember on a flight over the unbroken boreal forest, the tundra or the sea ice, that the Canadian North has been inhabited for many thousands of years. The populations that have occupied this great area were never large, but their skills as travellers and hunters made it possible for them to make use of virtually all the land without altering the environment. Because of extremely slow rates of plant growth and decay, signs of ancient occupation - old house remains, tent rings, fire-cracked rocks - are visible almost everywhere and it is not difficult for archaeologists to find, on or close to the surface, a wealth of artifacts and other evidence revealing the richness, diversity and breadth of Indigenous society.

The Indigenous peoples came originally from Asia, crossing the land bridge over the Bering Strait during the last ice age (see Beringia; Prehistory). The Athapaskan peoples arrived at least 12 000 years ago, eventually to occupy large tracts of land, including the Mackenzie Valley and the Yukon. The Inuit arrived about 4000 years ago, spreading throughout the Arctic, including all the coastal areas, practically all of the islands of the Arctic Archipelago to the Ungava Peninsula and as far east as the Gulf of St Lawrence and Newfoundland.

The Inuit occupy the shores of the Arctic Ocean and of Hudson Bay. Although the Inuit speak closely related dialects of the same language, regionally there are differences among them reflected in technology and social organization that even today complicate anthropological generalizations.

The Inuit themselves perceive important differences between their various groups; the Inuvialuit of the Mackenzie Delta see themselves as distinct from the Inuinnait (Copper Inuit), their neighbours to the east and the Copper Inuit - or Qurdlurturmiut - emphasize that they are unlike the Netsilingmiut, the Aivilingmiut or the Igloolingmiut, who live still farther east. Within each of these broad groups, finer divisions and distinctions exist, reflecting different patterns of land and maritime use and of changes in dialect, clothing and hunting techniques.

The Indigenous people of the Mackenzie Valley are part of the Athapaskan family and regard themselves, notwithstanding dialectical variation in their languages, as "the people," the Dene. Like the Inuit, they perceive important differences between their bands, the Gwich'in (Mackenzie Delta, northern Yukon and part of interior Alaska), Sahtu Dene (Mackenzie Mountains and Liard River valleys), Dogrib - or Tli Cho - (Great Bear and northern Great Slave lakes) and Chipewyan (Barren Lands along the borders of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.) More recent arrivals, the Cree (plains and forest country of the prairie provinces) migrated northward during the fur trade and exploration days.

The first Métis who moved into the North in the early 19th century settled around Great Slave Lake; they trace their ancestry to the unions between French Coureurs des bois and Indigenous women in the early days of the fur trade. In the aftermath of the North-West Rebellion of 1885, many Métis moved north and settled in the Mackenzie Valley. Other Métis, sometimes called "country-born," are the descendants of unions between Hudson's Bay Co men - mainly of Scottish origin - and Dene women. The children of these unions usually intermarried with the original Dene inhabitants, so close family ties exist between the Métis and Dene.

Economic Future of the North

The issues that concern the North today result from the presence of the non-Indigenous people, outsiders of mainly European origin whose advent was spearheaded by the explorers and fur traders seeking to extend the fur trade empire. The explorers and fur traders were followed or accompanied by missionaries and clergy, who were followed by representatives of government. The pattern of historical development in every region of Canada was reflected in the North, with one difference. The opening of the prairies by the construction of the CPR was followed by agricultural settlement, the establishment of many centres of non-Indigenous population and widespread diffusion of European language and culture.

In the North, however, where agricultural settlement is out of the question, it is nonrenewable resources - eg, gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper, oil and natural gas and, most recently, diamonds - that have spurred economic development. These industries do not promote widespread non-Indigenous settlement, but rather "instant" towns, eg, Dawson during the Klondike Gold Rush and more recently, Faro, the Yukon and Yellowknife, Tungsten and Pine Point in the NWT, with imported labour forces.

A large part of the non-Indigenous population is transient; even government employees are likely to regard their service in the North as a tour of duty limited to a few years. The Indigenous people therefore constitute, in the NWT, a majority of the permanent residents, and in the Yukon a very substantial minority. These facts will continue to bear significantly on the future of the North, for they make possible what was not possible when the West was opened up - the preservation of the great herds of migratory animals, the development of the Indigenous economy, and the establishment of political institutions that fully recognize the special place of Indigenous peoples.

The northern economy is mixed. The people living there have traditionally depended on renewable resource activities; eg, hunting, trapping and fishing for employment. The mining industry largely employs non-Indigenous people, as does the oil and natural gas industry. Both recently have sought to employ Indigenous people and to enter into business with Indigenous-owned enterprises. The federal and the territorial governments are now the largest employers of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. The North is perceived as Canada's last frontier. It is natural to think of developing it, of subduing the land, and extracting its resources to fuel Canada's industry.

Because many people are committed to the view that the economic future of the North depends solely on large-scale industrial development, policies concerning the North have often weakened or destroyed that sector of the economy based on renewable resources. Those who have earned a living by hunting, trapping and fishing have been regarded as unemployed and have come to so describe themselves.

These policies have brought serious pressures to bear on the Indigenous population, many of whom, as they try to continue to live on the renewable resources, experience relative poverty and suffer the loss of a productive way of life. If they relinquish their traditional ways of life, which are considered culturally important and a source of self-respect, then the devaluation of that way of life can and is already having widespread and dismaying consequences.

Land Claims

The Yukon First Nations, Inuit, Dene and Métis say the North is their homeland; they do not oppose industrial development in the North; they believe, however, that they are entitled to a measure of control over the pace of such development and a share in the wealth it may create. In their view, these goals will only be achieved if new political institutions that truly reflect the interests of the Indigenous peoples are established in the North. This implies a new set of political and economic priorities for northern development. It depends on the recognition of Indigenous land claims, for it is through their claims that the Indigenous people seek to preserve their languages, art, culture, values - their very identity.

In the mid-1970s, Indigenous peoples of the North were confronted by the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline to move Alaskan and Mackenzie Delta natural gas across northern Yukon and up the Mackenzie Valley to southern Canada and the US. They recognized if such a pipeline were built, it would open up the North before they were ready - before their claims were settled. Their leaders took advantage of high-profile public hearings chaired by Justice Thomas Berger and subsequent hearings chaired by Professor Kenneth Lysyk to tell the rest of Canada how important the settlement of their outstanding land claims were.

Pipeline construction was delayed and the Indigenous people used the opportunity to enter into negotiations with Canada and the territorial governments. Those negotiations were long and difficult. The process of land selection was particularly wrenching, especially for those who had always considered their land indivisible.

The negotiations were successful and the Inuvialuit Final Agreement was the first to be completed in June 1984. The Yukon claim was settled in principle in 1993 and has been followed by separate negotiations with each of the 14 bands in efforts to reach final agreements. The Dene and Métis claim was agreed to in principle in 1987; however, the Indigenous people of the Mackenzie Valley did not agree to ratify the claim when the time came to do so. Instead, several of the bands, the Gwich'in, Sahtu Dene and more recently the Tli Cho, entered into negotiations separately with the government. The Gwich'in land claim was finally settled in 1992; the Sahtu Dene settled in 1993. The Tli Cho land claim remains under active negotiation.

In the Arctic, the Inuit combined their political and land claim hopes in a proposal for a separate territory (Nunavut) north and east of the treeline. The claim was agreed to in principle in 1988. Prior to that claim being settled, the people of the North had agreed in a plebiscite (1982) to divide the NWT. The Inuit land claim was signed in 1993; division of the NWT into 2 territories took place on 1 April 1999.

Self-Government

All the northern Indigenous land claimants sought recognition of their political rights to Indigenous self-government within Canada. With the entrenchment of Indigenous rights in the Constitution Act, 1982, they claimed it as a right. That right has gradually received recognition, and for those who have already settled land claims, self-government negotiations have commenced or will do so in the near future. Several Yukon bands have already concluded self-government agreements. Talks are underway between Canada, the government of the NWT, Gwich'in and Inuvialuit; Tli Cho are negotiating land claims and self-government in integrated negotiations.

Development of the North

Development of the North need not be defined exclusively in terms of large-scale, capital-intensive technology. The possibilities of the renewable resource sector need not be ignored; eg, the fish and mammal resources of the NWT can provide sufficient protein for a human population in that region 2 to 4 times the present size. Already Muskoxen, Caribou and arctic char are marketed as gourmet foods outside of the North and there has been a limited commercial market of meat and fish within the territories. Future development might also include an expanded program of wildlife management and further carefully regulated harvest, with active involvement of Indigenous people.

At the same time Indigenous people are beginning to experiment with access to the economy of the dominant society. Their businesses, organized after the settlement of land claims, are involved in oil and natural gas exploration and development, transportation, service mining, and a variety of other sectors of the national and international economies.

The Yukon first nations, Dene, Inuit and Métis have advanced proposals for new political arrangements in the Yukon and the NWT. Already those proposals are shaping the political landscape. Whatever the outcome of these proposals, they are evidence of a renewed determination - and a new capacity - on the part of Indigenous people in the North to defend what they believe is their right to a future of their own.

Canadians share a mass culture with the US, but it is Canada that has a distinct northern geography and special concern for the North. Canada's achievements in the development of the North are in many ways unsurpassed; eg, the exploration and mapping of the Arctic by land and sea, the development of fur-collecting posts, the mining industry's discovery of uranium off the shores of Great Bear Lake in the 1930s and its extraction of base metals from the arctic islands in the 1980s. Gold has been found and extracted in the North for more than a century. Diamond discoveries have recently set off a fresh wave of mineral exploration.

The Canadian oil and gas industry and its engineers lead the world in the development of technology for the recovery of oil and gas in arctic waters. Since 1985, an oil pipeline has delivered Norman Wells oil to southern markets.

Progress tends to be equated only with industrial and technological advancement. Ultimately the form that northern development takes - political, social and economic - will reflect the beliefs that Canadians hold about the kind of society they want to build. In the North, however, the questions beneath the surface of our national life cannot be avoided. For many Canadians these questions make the North not simply a geographical area but a state of consciousness.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom