Traditional Territory

The Nisga’a people have lived in the Nass River Valley of Northwestern British Columbia since time immemorial. As of 2021, 1,794 Nisga’a still live on traditional lands along the Nass in the villages of Gitlaxt’aamiks (formerly New Aiyansh; considered the capital of the Nisga’a nation), Gingolx (formerly Kincolith), Laxgalts’ap (formerly Greenville) and Gitwinksihlkw (formerly Canyon City).

Traditional Life

The Nisga’a once practiced a balanced reliance on hunting, fishing and plant gathering. Some traditional foods included crab, black cod, halibut, salmon, herring eggs, seal, sea lion, clams, pine mushrooms, lowbush cranberries and mountain blueberries. They travelled by canoe and on foot to hunt and fish on their territories and to trade with neighbouring Indigenous nations.

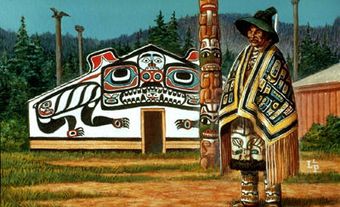

The Nisga’a lived in rectangular-shaped houses made out of cedar wood, known as plank houses (see Architectural History: Indigenous People). Their homes were often painted elaborately, decorated with family crests on the outside and with ceremonial objects, such as masks, on the inside. Cedar wood was also used for totem poles, canoes, baskets, hats, staffs, masks, rattles, baby cradles, drying racks, bowls, armour and more.

Social Organization

Every Nisga’a person belongs to a wilp (family group or house). Wilps own territory and are governed by one or more chiefs, depending on their size.

Nisga’a also belong to one of four clans, known as pdeek: Gisk’aast (Killer Whale/ Owl), Ganada (Raven/Frog), Laxgibuu (Wolf/ Bear) and Laxsgiik (Eagle/Beaver). Membership in a pdeek is determined by a matrilineal system, meaning that it is passed down through the mother’s line. This maternal clan inheritance also includes the rights to traditional names, songs, crests and dances.

Culture

The Nisga’a refer to their oral culture and traditional laws as Ayuuk. This also includes their belief system, traditional histories, identity, art and music. The Nisga’a strive to protect the Ayuuk and to pass it along to younger generations.

Potlatch

The Nisga’a participate in the potlatch feast — a gift-giving ceremony. Like many other Northwest Coast Indigenous peoples, and some Dene (Athabaskan peoples), the Nisga’a hold potlatches on the occasion of important social events such as marriages, births and funerals. The potlatch is also used to confer status and rank upon individuals, kin groups and clans, and to establish claims to names, powers and rights to hunting and fishing territories. Between 1884 and 1951, the potlatch was banned under the Indian Act, though it has since been reinstated and continues to be celebrated by various Indigenous groups today (see Potlatch Ban).

Totems

Totem poles (known as pts’aan) are a significant part of Nisga’a culture and identity. Totems display family crests, commemorate histories, people and events, and mark territory. Totem poles were (and still are) expensive to commission because only skilled artisans can create them. Some well-known carvers include Norman Tait, Roy McKay and Alver Tait. When totems were raised, celebrations ensued. Chiefs told traditional stories, held a feast and thanked the carver.

The Nisga’a totem tradition was nearly lost with the arrival of Europeans in the 19th century. Many missionaries destroyed totems, mistaking them for pagan statues. Some Europeans sent totems to be displayed in museums in other parts of North America and the world. However, the tradition has since been revitalized (see Repatriation of Artifacts). Nisga’a totem poles now stand on the banks of the Nass and throughout the world.

Traditional Histories

Known as adaawak, traditional histories provide information about Nisga’a territory and the animals, plants and people who live on it. The adaawak are considered property of the Nisga’a; this means only they have the right to tell these stories. While some adaawak are shared among all Nisga’a, others belong to a specific wilp.

Art and Music

In addition to totems, Nisga’a artists and carvers have created exceptional pieces of art including ceremonial masks, jewellery, and more.

Drumming and traditional dances are also important to Nisga’a culture. Music and dance are performed for entertainment, such as at festivals like the Nisga’a new year, Hobiyee (held every February), or for spiritual purposes during certain rituals.

Language

The Nisga’a language is sometimes known as Nass-Gitxsan, since Nisga’a and Gitxsan are mutually intelligible. There are three surviving forms of this language, which belongs to the Tsimshian family of languages: Nisga’a, Eastern and Western Gitxsan. Although formerly described as dialects of the same language, the Nisga’a and Gitkxsan consider themselves culturally distinct, and therefore refer to their languages as separate.

The Nisga’a language has five vowels: A, E, I, O and U. Long vowels are indicated as such in the spelling system by doubling the letter (e.g. long A is written AA; short A is written A). There are also a variety of consonant combinations, some of which produce soft and hard or front and back sound variations (as indicated by an asterisk (*): B, D, S, GW, H, HL, J, XW, G*, K*, KW*, L*, M*, N*, P*, T*, TL*, TS*, W*, X*, Y*

Nass-Gitxsan has been gradually replaced in use by English, but the Nisga’a have taken steps to preserve their language by teaching it in Nisga’a district schools and creating an online archive of words and phrases. Around 400 people in the Nisga’a villages are fluent in Nass-Gitxsan.

Religion and Spirituality

Before missionaries brought Christianity to the Nisga’a in the 19th and 20th centuries, the Nisga’a practiced their own faith and belief system. These spiritual practices, including vision quests, have since been revived and are practiced by some Nisga’a today.

The Nisga’a believe in spirits (naxnok) that can bring both good luck and bad. Traditionally, specially trained Nisga’a were said to control naxnok powers and use them to help or hurt others. Healers, known as Halayt or Medicine Men, were responsible for taking care of people’s spiritual and physical well-being. The Halayt used sacred songs and objects, such as rattles and masks, to cure sick people. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada).

Origin Stories

The Nisga’a believe in a Creator figure, known as K’am Ligii Hahlhaahl (Chief of Heavens). Although stories differ depending on the wilp, stories indicate that he sent to earth four clans of people — the ancestors of the clans that still exist to this day. The Creator put the people along the Nass River, the area around which remains their homeland. According to oral tradition, the Creator’s grandson, Txeemsim, created the sun, which saved the people from wandering in darkness. Although helpful, Txeemsim is also a trickster who gets into trouble and whose mistakes teach humans how to avoid error. Txeemsim is credited with beginning Nisga’a oral tradition because it is he who travelled the lands telling the Nisga’a all that he knew.

Colonial History

The Nisga’a first encountered Europeans when British naval captain George Vancouver sailed into the Nass River in 1793. The Nisga’a entered into a trade relationship with the Europeans, exchanging otter pelts for metal objects such as pots and knives. By the 1800s, the Hudson’s Bay Company began establishing trade posts along the Northwest Coast. The mouth of the Nass River soon became a hub for material exchange.

Interaction with European traders introduced changes to Nisga’a traditional life with the introduction of different tools and weapons. This interaction also brought new and deadly diseases to the Nisga’a, such as smallpox, influenza, tuberculosis and measles. These diseases significantly reduced Indigenous populations throughout the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.

A gold rush in British Columbia in the mid-1800s brought more outsiders into Nisga’a territory, including miners, explorers and their families. Christian missionaries also arrived during this period. They converted many Nisga’a and prohibited many traditional ceremonies. These restrictive policies were soon supported by federal legislation, such as the Indian Act.

In 1871, when British Columbia joined Canada (see British Columbia and Confederation), most of Nisga’a territory was declared Crown land, without any consultation with Nisga’a people. Effectively pushed off their traditional lands by outsiders, the Nisga’a were forced to occupy reserves around the Nass River.

The creation of residential schools forcibly removed Nisga’a children from their homes and families into boarding schools, where many were abused and forced to abandon their culture and language.

Land Claims and Self Government

Since the late 19th century, the Nisga’a have petitioned the federal government to recognize their ownership of traditional lands. In 1907, the Nisga’a established the Nisga’a Land Committee, which issued petitions, protest notices, and land claim actions. In 1913, one of these petitions had been refined into a legal document laying claim to land in the Nass Valley. The document stated that the Nisga’a had occupied this area “from time immemorial.”

After several decades, the Nisga’a went to the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1969 (see Calder Case) to obtain a declaration that they had never surrendered title to their traditional lands, either by treaty or otherwise. Dismissed in BC courts, their contention was taken to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). In 1973, the SCC judges split evenly on whether the title continued to exist.

After years of negotiations, the Nisga’a people signed and ratified a historic agreement-in-principle with Canada and BC on 22 March 1996. This extensive document laid the foundation for the Nisga’a Final Agreement, the first modern-day land claims agreement in BC.

The Final Agreement calls for payments to the Nisga’a of approximately $190 million over a period of 15 years, and recognizes the communal ownership and self-governance of about 2,000 km2 of Nisga’a lands in the Nass River Valley (thereby reclaiming former reserve lands as their own). The agreement recognizes Nisga’a ownership of resources on these lands and spells out entitlements to salmon stocks and wildlife harvests. The agreement was signed and the provincial legislation passed in 1999, which ratified the treaty, and on 11 May 2000, the treaty came into effect. The landmark agreement is the first in BC to provide constitutional certainty of an Indigenous peoples’ right to self-government.

Today, the Nisga’a Lisims Government is the governing body of the Nisga’a nation. This government can pass laws on certain matters concerning the Nisga’a people, but the federal and provincial governments also have certain legal jurisdiction (authority). The Nisga’a Government has three levels: the Nisga’a Lisims Government (central authority), four Nisga’a Village Governments (each a separate and distinct legal entity) and three Urban Locals. In 2013, the Nisga’a became the only First Nation in Canada to privatize its land, allowing members to purchase land on the property.

Contemporary Life

As of the 2021 Census, 4,890 people identified as Nisga’a. The Nisga'a nation is actively involved in the management, contracting and employment areas of natural resource industries on their territory, including fishing and forestry. The Nisga’a also strive to protect and promote the environment as well as their language, culture and Indigenous rights.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom