Founding and Mission

In May 1966 in Toronto, Laura Sabia, President of the Canadian Federation of University Women, formed a coalition of some 30 women’s organizations to demand that Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson establish a royal commission on issues affecting women. With the support of Canadian author Doris Anderson, then editor-in-chief of Chatelaine, the Committee for the Equality of Women in Canada launched a lobbying campaign, but it lasted only a few months. Nevertheless, growing pressure from the media, and perhaps Sabia’s threat of a two‑million woman march on Parliament Hill, convinced the prime minister to establish the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada on 3 February 1967, with Florence Bird as its Chair.

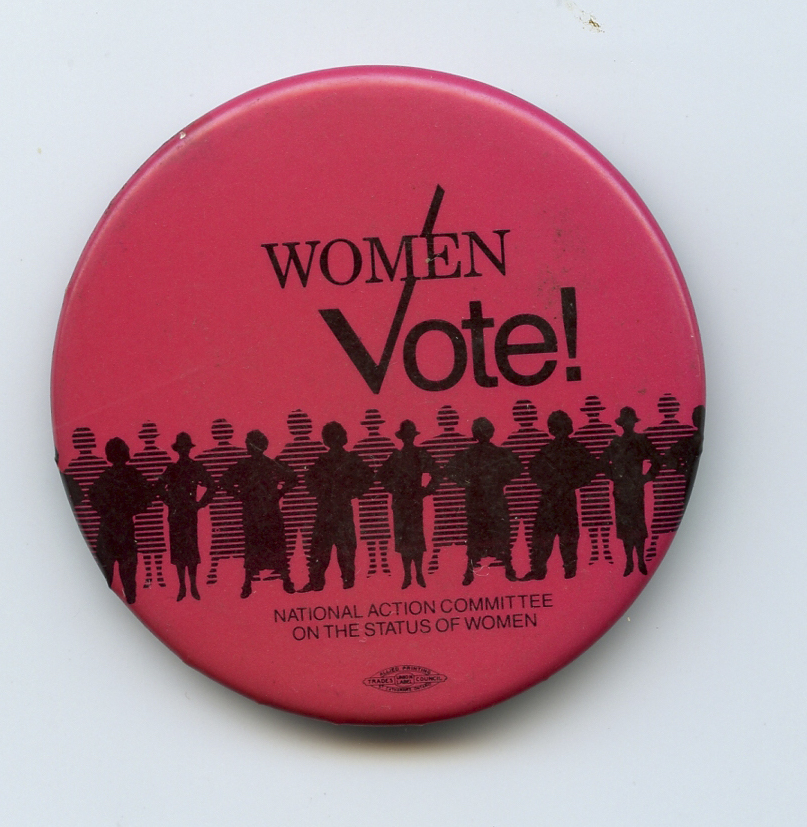

Once the commission had tabled its report in December 1970, the coalition members met again and resolved to do everything possible to get the government to implement the report’s main recommendations. (The report contained a total of 167 recommendations, on issues such as daycare, birth control, maternity leave, family law reform, education and pensions.) On 30 January 1971, the coalition adopted the name National Action Committee on the Status of Women and the objective of co-ordinating information and action among the various women’s organizations throughout Canada.

Composed of 30 member groups at its founding, the NAC continued to grow over the ensuing years. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was considered the main feminist pressure group lobbying the Canadian government and the official voice of a multitude of member and affiliated organizations supporting gender equality. As of 1997, the NAC represented over 700 groups across the country and was the largest umbrella organization for women’s groups in Canada. The NAC’s annual general meeting, attended by delegates from its member organizations, was the forum where a great many issues, as well as a vote on the positions to be adopted, formed the basis for the NAC’s lobbying activities.

Demands

Because the NAC was fighting for equality and social justice for all women, its main demands were for changes to improve the status of women, particularly with regard to children’s services, domestic violence, poverty and minority rights. In addition to lobbying for such causes at the provincial and municipal levels, the NAC participated in conferences and other activities to promote solidarity among women internationally and to demand equal rights for women throughout the world.

Because the NAC depended on government grants for 90% of its funding, for many years it kept away from partisan politics and focused on lobbying. In 1984, it achieved a major media coup when it held the first (and, to this date, still the only) televised party leaders’ debate on women’s issues during a federal election campaign. While the NAC was divided on the 1987 Meech Lake Accord, it openly denounced the Charlottetown Accord of 1992.

Recent History

As a result of its opposition to the Accord, the NAC saw its funding cut first by the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney and then by the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien. From $13 million in 1989, the budget envelope for women’s organizations had shrunk to only $8 million by 1998. As a result, in the early 2000s, having accumulated a debt of $100,000 and having had to shut most of its regional offices, the NAC was forced to suspend its activities.

In 2005, after many attempts, the NAC received a $150,000 grant from Status of Women Canada to begin restructuring itself and to plan a conference that was held the following year. (At the time, the NAC was relying on members’ dues, donations, project grants and special events to fund its operations.)

However, as a result of the budget cuts that the Conservative government of Stephen Harper began imposing on Status of Women Canada in 2006 and the elimination of the objective of promoting equality from this agency’s mandate, as well as the inability of research groups and rights-advocacy groups to access its funding programs, the NAC’s future began to seem shaky once more. A key partner, the Canadian Congress of Labour, also withdrew its support for the NAC. In 2007, the NAC submitted a brief to the House of Commons on the impact of these changes in the funding of Status of Women Canada, but was not invited to make a presentation on this brief before the committee. This was one of the NAC’s last public interventions and the group dissolved in the late 2000s.

Presidents

The presidents of the NAC have included many prominent activists in the struggle for women’s rights and sexual equality. The NAC’s first president was Laura Sabia. The second was labor leader and union activist Grace Hartman, who held the post for just a few months before becoming national president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees. (Hartman thus became the first woman to hold the top position in a national union in Canada). The NAC’s fourth president was feminist and peace activist Kay Macpherson, who made her mark first in the early 1960s in the organization Voice of Women, which she helped to found, and then in the Canadian Association for Repeal of the Abortion Law, created to protest the imprisonment of Dr. Henry Morgentaler.

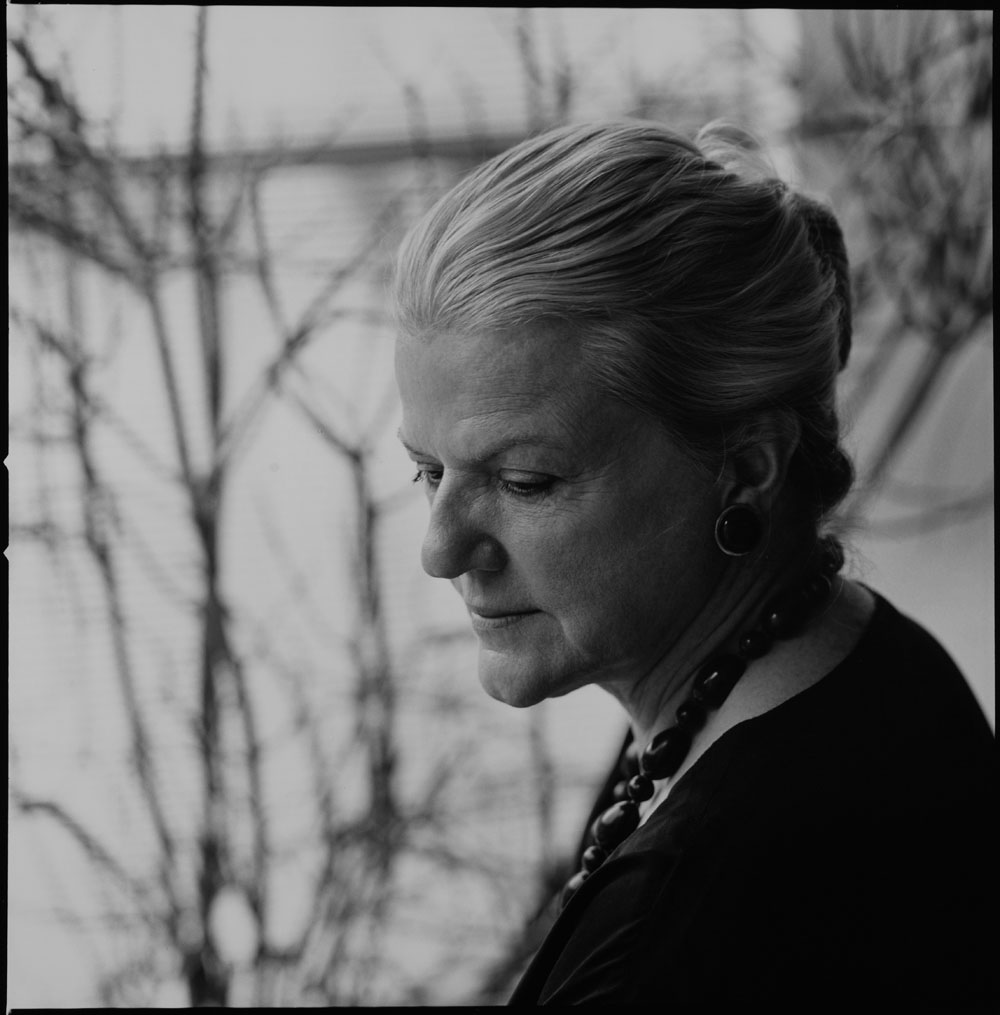

In 1982, Doris Anderson, a former editor-in-chief of Chatelaine magazine, became president of the NAC after resigning from the presidency of the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women (CACSW). Like many other Canadian women, Anderson believed that the new Constitution Act, 1982 and the new Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms did not provide sufficient support for women’s rights. Her highly publicized resignation from CACSW helped draw attention to a special conference on the status of women, the Women’s Constitution Conference, which the government had tried in vain to prevent from being held. The lobbying campaign that emerged from this conference resulted in the addition to the Charter of a new section that guaranteed rights and freedoms equally to males and females.

Following Anderson in the mid-to-late 1980s, the NAC’s next two presidents were the academic Chaviva Hošek and the lawyer Louise Dulude (the first and still the only francophone to have headed the NAC). The following two presidencies, of Lynn Kaye and Judy Rebick, were profoundly marked by two issues: antifeminism (in the wake of the Polytechnique Tragedy; see Antifeminism in Québec) and the right to abortion (following the ruling of the Supreme Court of Canada in Tremblay v. Daigle).

With the election of its next two presidents — Sunera Thobani, a Tanzanian woman of South Asian origin, in 1993, and Joan Grant-Cummings, the first Black Canadian woman to head the organization, in 1996 — the NAC began placing more emphasis on issues affecting women who were immigrants or member of visible minorities. Thobani and Grant-Cummings also gave special attention to Indigenous women’s issues. In 2000, Terri Brown became the first Indigenous woman to serve as president of the NAC. She is now chief of the Tahltan nation in British Columbia and helping to lead the campaign to investigate the deaths and disappearances of hundreds of Indigenous girls and women (see Highway of Tears). The NAC’s last elected president, Dolly Williams, has distinguished herself through her dedicated work within the Congress of Black Women of Canada. She also sits on the Board of Directors of the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia.

See also :Women's Movements in Canada; Women and the Law.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom