Mount Royal is a short mountain with a wide base covering ten square kilometres. It is close to the geographic centre of the Island of Montreal. Mount Royal is Montreal’s defining physical feature and a protected site; it was designated a Historic and Natural District by the government of Quebec in 2005. By law, new buildings in Montreal may not be taller than Mount Royal. The mountain occupies a central position, not only in the urban landscape of the city of Montreal, but also in its history, culture and society.

Physical Characteristics and Territory

Mount Royal is composed of three summits: Colline de la Croix (the central peak where the Mount Royal Cross is located), Colline d’Outremont and the Westmount Summit. The central peak rises to 233 meters. Mount Royal was formed about 125 million years ago by an intrusion of magma. Its landscape was then shaped by receding glaciers during the last Ice Age. It is not an extinct or dormant volcano, though it has often been incorrectly described as one. Mount Royal is one of several large hills or small mountains that form the Monteregian Chain. The mineral montroyalite was discovered at the Francon quarry in Montreal’s East End and was named after the mountain.

The mountain has four cemeteries which occupy much of the northern parts of the mountain. A number of institutions, such as universities, hospitals, private colleges and St. Joseph’s Oratory, also occupy large areas of the mountain domain. (See Université de Montréal; McGill University.) There are also some residential areas that were built on parts of the mountain as well.

History

As the defining landmark of the Island of Montreal, Mount Royal has always been closely associated with the history of human habitation on the island.

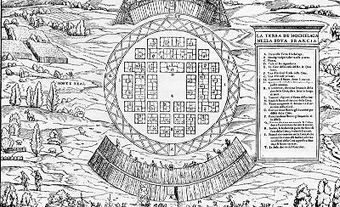

One of the earliest evidence of human habitation on the Island of Montreal — the Dawson site — is by the Mount Royal. According to the account of Jacques Cartier, the village of Hochelaga was located close to the mountain. Indigenous villages may have been built on the southern/eastern side of Mount Royal to protect them from cold winter winds that blow from the Northwest. In October 1535, Cartier was guided to the top of Mount Royal during his second voyage. He remarked that he could see the St. Lawrence River from its summit. It is Cartier who named the mountain “Mount Royal.” Montreal is a contraction of “mont” and “réal,” which in 16th century French was used interchangeably with the word ”royal”.

DID YOU KNOW?

In 2017, the park atop the Outremont Summit was renamed to Tiohtià:ke Otsira’kéhne Park (“the place of the big fire” in kanyen'kéha, the Mohawk language).

Over a century later, Mount Royal was the site of a pilgrimage made by Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve, and the early settlers of Ville-Marie. A terrible flood had threatened to destroy the settlement around Christmas Day 1642; Maisonneuve pledged to put a cross atop the mountain if his village was spared. In early 1643, he made good on his promise, placing a wooden cross on the mountain. The illuminated steel cross that stands on top of the mountain today was installed in 1924 and commemorates this event.

As Montreal grew in size and importance in the late 18th century and beginning 19th century, the south-eastern slope of Mount Royal became home to some of the city’s wealthiest merchants. James McGill’s summer estate was one such property, and it would eventually become the site of McGill University.

Throughout history, Mount Royal played a key role for burials. Indigenous people buried their dead on Mount Royal long before European colonization. By the mid-19th century, Montreal’s few cemeteries — nearly all of which were located in the most densely populated parts of the city — were full. Moreover, public health authorities were concerned about the effect of decomposing bodies in urban environments. The city’s cemeteries also constrained development. Beginning in 1852, the far north side of Mount Royal began to be used as a cemetery by Protestant anglophones. In 1854, the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery was established for the city’s francophone Catholic community; it is today the largest cemetery in Canada. Also in 1854, Montreal’s first Jewish cemetery — Shearith Israel — was established on Mount Royal; this was followed in 1863 by Shaar Hashomayim. These are some of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Canada.

As the city grew in size and population, many important institutions also settled on the mountain’s sides. Collège de Montréal and Collège Notre-Dame moved to the mountain in the late-19th century. Hospitals, like Hôtel-Dieu and the Royal Victoria Hospital, took up residence on or near Mount Royal. The medical thinking of the era was that patients should be close to nature to improve their chances of recovery. (See Hospital.)

Mount Royal Park

In the 19th century, many of Montreal’s most prominent citizens bought large tracts of land around its base. Some of the tracts were used as orchards or farms. (See Agriculture in Canada.) As the city grew in size, it also became more congested and green spaces became insufficient; Montrealers increasingly turned to the mountain for recreation and leisure. This put the people of Montreal into conflict with the people who were still using the mountain for its resources. The cutting of trees for firewood in 1859 led to a public campaign to protect the mountain and preserve it as a park for public enjoyment.

In 1874, the city hired famed American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to design the new park, which was officially opened to the public in 1876. (See Landscape Architecture.) Though it was not completed to Olmsted’s original design, the park is an indispensable part of Montreal’s culture; it preserve a kind of wilderness in the heart of the city.

In the 1940s and 1950s, there was a moral panic about a section of Mount Royal Park that was thought to be frequented by “undesirable people.” This referred to people with drug and alcohol abuse problems (see Alcoholism; Nonmedical Drug Use), the unhoused and people with severe mental health issues. Colourful newspaper articles of dubious accuracy also insinuated that the park was being used for, what was then considered, inappropriate or immoral sexual relationships. Members of the city’s LGBTQ+ community were singled out and subjected to harassment by the Montreal police morality squads for many years. (See Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights in Canada.) Mayor Jean Drapeau, who had campaigned on a law and order platform, vowed to address the problem head on. He ordered the Montreal Parks Department to clear out the underbrush and cut down many trees to eliminate any places where people might hide. This gave Mount Royal a peculiar appearance, such that locals began to call it “Mont Chauve” (Bald Mountain).

Today, the park is used for a wide variety of leisure and sporting activities. There are several lookouts, the largest of which is called the Kondiaronk Belvedere. The belvedere was named in honour of the Huron-Wendat Great Chief Kondiaronk, who facilitated the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701. This lookout and its chalet are large enough to accommodate large crowds and have been used for concerts. The belvedere offers a dominant view on downtown Montreal and beyond.

Beaver Lake, an artificial pond, was built in 1938. Until 2008, ice skaters would use the lake for recreational purposes. Since then, a nearby artificial rink is used. (See Ice Skating.) The modern-style pavilion besides the lake was built in the 1950s.

The Smith House is one of the few remaining farmhouses on Mount Royal. It reflects the agricultural uses of the north side of Mount Royal. Smith House was also used as the park superintendent’s residence, in addition to an arts centre and a hunting and nature museum. Today, it is used by the mountain’s main conservancy group, Les Amis de la Montagne (The Friends of the Mountain). It serves as a welcome centre and museum detailing the mountain’s history.

Fletcher’s Field and Jeanne Mance Park

A wide open plateau, once called Fletcher’s Field, occupies the northeastern side of Mount Royal Park. The field runs from Mount Royal Avenue in the north to Pine Avenue in the south and is bisected by Parc Avenue in the middle. On the eastern side of Parc Avenue is Jeanne Mance Park, which is mostly dedicated to playgrounds and sports fields. Although it used to be part of Fletcher’s Field, it was officially renamed in honour of Jeanne Mance — cofounder of Montreal — in 1990.

Fletcher’s Field has long been a popular location for a variety of leisure activities and festivals, both formal and informal. In the late 19th century, Fletcher’s Field was used as a provincial exhibition ground. Montreal’s replica of London’s famous Crystal Palace was notably rebuilt there in 1878 (until destroyed by a fire in 1896). Horse racing was also practiced at this site. Fletcher’s Field was also the first home of the Royal Montreal Golf Club. (See Golf.)

Fletcher’s Field has historically been used by both professional and amateur musicians. The latter used the mountain as a space to practice. Musicians interested in African music and drumming began holding regular practice sessions in Fletcher’s Field on the weekends. Over time, this evolved into a Montreal cultural tradition known as the Tam Tams. During the warmer months, drummers congregate around the George-Étienne Cartier Monument in a massive drum circle on Sunday afternoons. The Tam Tams are entirely spontaneous and are not officially organized by the City of Montreal

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

,_2016_(30216916871).jpg)