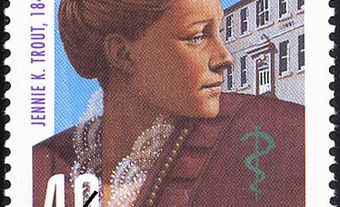

Maude Elizabeth Seymour Abbott, cardiac pathologist, physician, curator (born 18 March 1868 in St. Andrews East, QC; died 2 September 1940 in Montreal, QC). Maude Abbott is known as the author of The Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease (1936), a groundbreaking text in cardiac research. Though Abbott graduated in arts from McGill University (1890), she was barred from studying medicine at McGill because of her gender. Instead, she attended Bishop’s College (now Bishop’s University), earning a medical degree in 1894. As assistant curator of the McGill Medical Museum (1898), and curator (1901), she revolutionized the teaching of pathology by using the museum as an instructional tool. Abbott’s work paved the way for women in medicine and laid the foundation for modern heart surgery. (See also Women in STEM).

Early Life and Education

After Maude Abbott was born in St. Andrews East, Quebec, in 1868, her father, Jeremy Babin, left the family for the United States. In October 1869, her mother died of tuberculosis. This left Maude and her elder sister, Alice, in the care of their maternal grandmother. They changed their last name to Abbott. Despite this turbulent start, Maude had a happy childhood. She often wrote in her diary of her desire to go to school.

Entry from March 1884

One of my day-dreams, which I feel to be selfish, is that of going to school… Oh, to think of studying with other girls!

Abbott got her wish when she was accepted to the Misses Symmers and Smith School in Montreal. She excelled in her studies and earned a scholarship to McGill University, which had just recently opened its doors to women (1884). According to her memoir, a conversation with a friend during her second year at McGill inspired her to become a doctor. When she asked her grandmother if she could become a doctor, her response was, “Dear child, you may be anything you like.” Abbott initially applied to study medicine at McGill. She was promptly rejected, as the faculty would not accept women into their program. She settled for earning her MD at Bishop’s College (now called Bishop’s University), though she noted that the experience was far less enjoyable. Even so, she remained a dedicated scholar, earning the Senior Anatomy Prize and the Chancellor’s Prize for the best examination in her final year.

Abbott graduated from Bishop’s College in 1894 and spent three years studying in Europe. There she took additional courses in pathology and gained valuable experience at women’s hospitals and an asylum.

Early Career and McGill Medical Museum

In 1897, Maude Abbott returned to Montreal and opened a private practice, often treating women and children. By 1898 she was made assistant curator of the McGill Medical Museum. However, Abbott was unsatisfied with the perceived lack of professional growth that the museum position offered. In a letter to Dr. George Adami, dated January 1899, she said, “I find work in the laboratory somewhat difficult in your absence, with no position or definite work assigned me.… Could I not do something else till your return while still keeping an eye on the ascitic fluids?”

Did you know?

McGill University didn’t admit its first female medical students until 1917, nearly two decades after Abbott’s appointment as assistant curator for the McGill Medical Museum.

Abbott travelled to Johns Hopkins University in December 1898 to observe the collections of other medical institutions. There she met Dr. William Osler, who would later ask her to contribute a chapter on congenital heart disease for his book System of Medicine (also called Modern Medicine) (1907). Osler praised Abbott’s work as “the very best thing ever written on the subject.” This research would significantly shape her later career.

By 1901, Abbott was promoted to curator. Around this time, she began informal teaching demonstrations for medical students at McGill. These demonstrations proved to be so popular that they became a mandatory part of the curriculum.

Abbott spent years organizing and expanding the museum’s collection but faced a major setback when a fire broke out in 1907. The museum lost approximately two thirds of its collection. An appeal to the International Association of Medical Museums (which Abbott co-founded in 1906) resulted in the donation of approximately 3,000 specimens to the collection between 1907 and 1910, all of which was managed and categorized by Abbott.

Later Career

In 1910, Maude Abbott received an honorary medical degree from McGill University, in recognition of her work for the school. She also received a lectureship in the Pathology Department. However, some of her male colleagues insisted on referring to her as “Miss Abbott” instead of “Dr. Abbott.” In 1919, she was offered a professorship in pathology and bacteriology at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. They offered her a higher salary, but she did not accept until 1923. After two years there, Abbott returned to McGill, where she was promoted to assistant professor, though she was never promoted beyond this rank.

Abbott also helped found the Federation of Medical Women of Canada in 1924. Upon her retirement in 1936, McGill awarded her a second honorary degree for her work as “a stimulating teacher, an indefatigable investigator and a champion of higher education.

Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease

In 1931, Maude Abbott displayed artefacts from the McGill Medical Museum’s extensive collection — diagrams, photos, and large drawings — as part of an exhibit for the New York Academy of Medicine. She brought the same exhibit to the Centenary Meeting of the British Medical Association in London in 1932, where the British Medical Journal described it as “one of the most attractive parts of the museum.” The exhibit also caught the attention of Dr. Seecof from Montreal. He suggested that she should preserve the illustrated portions in an atlas. Abbott’s research culminated in The Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease, which was published by the American Heart Association in 1936 to immediate success.

Significance and Legacy

Maude Abbott died on 2 September 1940 after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. The medical community mourned her loss. In his address to the New England Heart Association in December 1940, Dr. Paul White referred to Abbott as “a living force in the medicine of her generation.” He said, “our knowledge of congenital heart disease… [is] due directly to Maude Abbott’s influence.” Her best-known achievement, the Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease (1936), proved to be a life-saving resource. It helped doctors better understand and diagnose heart defects and develop new ways to treat them. She is considered a pioneer who paved the way for women in medicine.

Did you know?

On 8 March 2019, Maude Abbott was designated as a historic figure by the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications du Québec. That same year, the Commission de typonomie du Québec, named an island in the Rivière du Nord near Saint-André-Est as île Maude-Abbott.

Honours and Awards

- Lord Stanley Gold Medal (1890)

- Senior Anatomy Prize, Bishop’s College (1894)

- Chancellor’s Prize, Bishop’s College (1894)

- Person of National Historic Significance, Parks Canada (1993)

- Inductee, Canadian Medical Hall of Fame (1994)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

Medical Building, McGill University, Montreal. QC, about 1900, courtesy of McCord Museum/VIEW-3619.

Medical Building, McGill University, Montreal. QC, about 1900, courtesy of McCord Museum/VIEW-3619.