Background

With the discovery of vast fossil fuel reserves at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, in 1968, government and petroleum industry players began to promote the idea of a pipeline connecting Alaska with US markets to the south. Drawing from Canadian reserves along the way, the pipeline would cross Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Alberta. That year, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau created the Task Force on Northern Oil Development to assess the feasibility of such a project. Its work resulted in the federal government’s official policy on pipeline development in the North, the Northern Pipeline Guidelines, published in 1970 and expanded in 1972. The Guidelines provoked a spate of engineering and environmental studies, public-policy reviews and economic analyses unequalled in Canadian history.

Early Proposals: Arctic Gas and Foothills Pipelines

Detailed proposals were put forward by two consortiums in the early 1970s. Canadian Arctic Gas Pipeline Ltd., composed of 27 Canadian and American producers (including Exxon, Gulf, Shell and TransCanada PipeLines), proposed a route from the Prudhoe Bay fields in Alaska, across northern Yukon to the Mackenzie River delta and then south to Alberta, where it would connect with US delivery systems. The Arctic Gas pipeline would have been the longest in the world (3,860 km) and the largest-ever private investment in a construction enterprise, costing an estimated $8 billion for the Canadian portion alone. Foothills Pipe Lines Ltd., formed by Alberta Gas Trunk Line (now NOVA Chemicals Corporation) and Westcoast Transmission, proposed a shorter route that initially ran from the Mackenzie Delta to Alberta. This Foothills line would have delivered gas from the delta to Canadian markets only. In 1976, however, Foothills began to promote an alternative route that would follow the Alaska Highway, connecting Alaskan reserves with the Lower 48 states.

The impact of these projects on the economy, environment and Indigenous communities of the North would have been significant. Furthermore, building a pipeline over permafrost presented monumental engineering challenges. Both proposals entailed burying the pipeline, which would disturb the natural temperature of the ground. This would in turn cause a phenomenon called frost heave — an upward swelling of the ground that could damage the pipe.

Berger Commission

A federal royal commission, led by Justice Thomas Berger, was appointed in March 1974 to consider the proposals along with their environmental, cultural, social and economic impacts on the North. The commissioners held community hearings across the Northwest Territories and Yukon, beginning in March 1975 and ending in November 1976, to document the concerns of Indigenous people and environmentalists.

The commission’s report, issued in April 1977, concluded that a pipeline from the Mackenzie Delta down the Mackenzie Valley to Alberta was feasible, but should proceed only after further study and after settlement of Indigenous land claims. The commission was adamantly opposed, however, to the building of a line across the delicate environment of northern Yukon. Berger concluded that a Yukon pipeline would threaten caribou and other wildlife upon which the Vuntut Gwich’in relied for their survival. To allow for the settlement of land claims in the Mackenzie Valley corridor, Berger recommended a 10-year moratorium on construction. The government accepted this term.

Amid declining oil and gas prices, the highly politicized Arctic Gas and Foothills proposals were shelved. The commission itself marked a turning point in the history of resource development in Canada. Its public consultation process was unprecedented, and Berger’s report humanized the complex set of cultural and environmental concerns at stake for Indigenous peoples in the North.

The land-claim settlement process took much longer than the 10 years Berger had anticipated, continuing throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s. By 2000, however, the Inuvialuit, Gwich’in and Sahtu Got’ine had all reached agreements with the federal government, and there was strong support for a pipeline among communities in the Mackenzie corridor (see Mackenzie Valley Pipeline: Maclean’s). That year, the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, the Gwich’in Tribal Council and the Sahtu Pipeline Trust formed the Aboriginal Pipeline Group to represent First Nations’ interests in a new Mackenzie Valley proposal. (The Dehcho were the only people in the region whose land claim remained unresolved.)

Mackenzie Gas Project

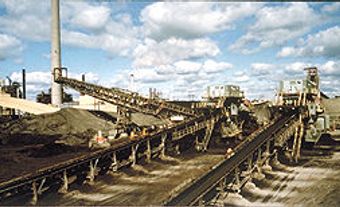

In 2000, a joint venture between Imperial Oil, ConocoPhillips Canada, ExxonMobil Canada and the Aboriginal Pipeline Group revived plans for a pipeline in the Mackenzie Valley with a $16.2 billion proposal called the Mackenzie Gas Project. In addition to a pipeline that would carry up to 34.3 million cubic metres of natural gas approximately 1,200 km per day from the Beaufort Sea in the Northwest Territories to northern Alberta, the plan included a gathering system and gas processing plant.

Imperial Oil and its partners submitted their application to Canada’s energy regulator, the National Energy Board (NEB), in 2004. The NEB approved the plan in 2010 and set 31 December 2015 as the deadline to begin construction.

In August 2015, Imperial asked for an extension to 2022, stating that it needed more time to assess the strength of the North American natural gas market, which had experienced a decline in prices. Environmental groups such as Alternatives North and Ecology North argued against the extension. They cited increased climate-change awareness, a change in federal government since the pipeline was approved, and evolving energy markets as reasons to halt the project. In June 2016, the NEB decided that the proposal was still in the public interest and approved the extension. However, in December 2017, Imperial Oil announced that the Mackenzie Gas Project had been cancelled and the partnership dissolved, citing changes in the North American natural gas market, along with increased competition from new sources and methods of gas extraction.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom