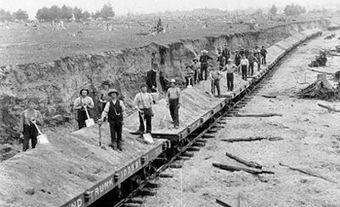

Labour law governs collective bargaining and industrial relations among employers, their unionized employees and trade unions. In Canada a distinction is commonly made between labour law narrowly defined in this way and employment law, the law of individual employment relationships, comprising the common law of master and servant and supervening statutory enactments governing the workplace. In England, labour law describes both, and of course a close relationship exists between them. In most provinces these matters are covered in separate statutes, but the Canada Labour Code is Parliament's major enactment governing the workplace for industries within federal jurisdiction, and regulates labour standards and occupational health and safety.

As soon as there were unions in Canada, there were labour laws (see working-class history), and although it was long thought that these could be enacted by the federal government nationally, in 1925 the Judicial

Committee of the Privy Council determined that in the Canadian federal system it was the provinces which had such jurisdiction in a general sense, the jurisdiction of Parliament to enact labour law being limited to certain discrete, albeit major industries

- eg, banking, telecommunications and transportation. Prior to the advent of modern labour relations law, the process of collective bargaining was not legally enforceable. Trade unions enjoyed either no, or only limited, legal status and collective agreements

were not recognized as contractually binding. The viability of collective bargaining rested solely on the economic strength of the parties and was often maintained by recourse to economic sanction. Workers used the strike for several purposes: as an

instrument of persuasion to induce employers to recognize a trade union as their bargaining agent; as an instrument of negotiation to achieve desired terms and conditions of employment within a collective agreement; and as an instrument of relief to

resolve disputes arising under a collective agreement once achieved. In this era, the industrial relations system was characterized by instability, labour unrest and widespread interference with production.

Modern labour law provides greater stability and ensures more orderly production by regulating the strike, replacing its use as an instrument of persuasion by the process of certification; replacing its use as an instrument of relief by the process of arbitration; and restricting its use as an instrument of negotiation to a variety of timeliness requirements.

It was not until 1944 that a full national system of collective labour-relations law was established by the federal government, exercising its wartime emergency powers to legislate in spheres ordinarily reserved for provincial legislation by promulgation of regulation PC 1003. After the war it was replaced by federal and provincial legislation (see Labour Relations), eg, Industrial Disputes Investigation Act of 1948 subsequently replaced by the Canada Labour Code and cognate provincial legislation each application in their respective spheres of jurisdiction. These statutes, variously called labour codes, labour or industrial-relations acts or trade-union acts, are all rooted in PC 1003 and are based on the idea, expressed in the preamble to Part V of the Canada Labour Code, that "the common well-being" is promoted "through the encouragement of free collective bargaining and the constructive settlement of disputes." At the heart of labour law lies the volatile ideological issue of how completely the state should regulate the use of economic power by both labour and management in bargaining over wages and other terms or conditions of employment. In the Canadian industrial relations system, collective bargaining generally takes place at the plant level between a single employer and its employees, although in certain sectors (construction, broad based multiemployer industry) wide bargaining takes place.

The Canada Labour Code and each cognate provincial statute protects the right of employees to join the union of their choice by making it an unfair labour practice for an employer to discriminate against employees for joining a trade union or participating in any of its lawful activities. Moreover, the employer is required by law to bargain in good faith with the union chosen as bargaining agent by a majority of his employees. To protect these rights each statute provides for the appointment of a labour relations board, to which complaints of unfair labour practices may be taken and which, upon application filed by a trade union to be certified as a bargaining agent, decides whether a majority of the employees in question wish to be represented by that union. In deciding whether to certify a union, the board must determine the "appropriate bargaining unit," - ie, the group of employees by whom and for whom the selection of the bargaining agent is to be made. Once the appropriate bargaining unit is determined, the labour relations board must ascertain the wishes of the majority by examining dues, receipts and other evidence of membership in the union or by administering a secret-ballot vote, or both. In addition to the legislation there are regulations, practices, countless decisions by labour boards and many court judgements that make up the labour law governing unfair labour practices, union certification and the duty to bargain in good faith.

Once a union has been certified it is entitled to require the employer to meet with its representatives and bargain over the terms and conditions of employment that will form the collective agreement for the employees in the bargaining unit. Either the union or the employer may apply to the minister of labour for the province (or for Canada if the industry is under federal jurisdiction) for conciliation and must do so before either party can engage in economic sanctions (see Labour Mediation). If no collective agreement is reached by that process, and in some provinces after a strike vote, the employees can lawfully strike. In some jurisdictions an employer is entitled to have its final offer presented directly to the employees and voted upon, whether before or after strike action has been taken. Legally, a strike is a concerted withdrawal of labour; at that same point in the process the employer can legally lock the employees out. Usually in a strike or lockout everybody loses something: the employer his profits and continuing costs, the employees their wages and the union its strike funds.

It is generally believed that the fear of this mutual loss is the driving force behind collective bargaining. In most cases the union and the employer sign a collective agreement without a strike. The agreements must be of at least one year's duration, and depending on the economic climate, may extend for up to 3 or more years. During that time any strike or lockout is illegal and no other trade union may seek to represent employees in the bargaining unit, nor may employees seek to terminate the trade union's bargaining rights. When the agreement expires the process of collective bargaining, conciliation and strike or lockout starts again. It is only in the interim, or "open" period between collective agreements that provision is made for employees to seek to terminate a trade union's bargaining rights, or for another trade union to apply to be certified as a bargaining agent of the employees in the bargaining unit, displacing the existing certified bargaining agent.

The ordinary criminal law and the law of torts and delicts determine the legal limits on picketing and other union activity in support of a strike, although in some provinces special laws limiting such activities are administered by labour-relations boards. Strikes are usually lawful and peaceful and are concluded by the signing of a collective agreement, but not necessarily. If the employer wins the strike or lockout so completely that no collective agreement is reached, the employees' jobs are protected only by the unfair labour-practice laws and individual employment law. Aside from the legal aspects of strikes, their economic, political, social and personal implications may be very important.

In public sector collective-bargaining relationships, federal or provincial law may substitute interest ARBITRATION (which is otherwise noncompulsory) for the right to strike, particularly when essential services are involved. The interest arbitrator's function is to establish the terms of the collective agreement upon which the parties have been unable to agree, usually the amount of the wage increase, but certain nonmonetary conditions of employment can be equally or even more contentious. The outcome of interest arbitration is intended to ensure terms and conditions of employment which correspond to those which are standard for employees doing comparable work.

When a collective agreement is in force, it becomes, in effect, the private law of the employer, the employees and the union. Disputes over the application, interpretation or breach of the collective agreement are settled through a grievance procedure which leads finally to grievance arbitration, a process made mandatory by Canadian labour legislation. Although courts will not determine the merits of a grievance dispute, arbitration is not always the final step because application may be made to the courts if arbitrators do not perform their functions properly. The enormous number of arbitration awards and court judgements relating to arbitration comprise the most practically important, if not the most newsworthy, component of labour law. For every strike there are tens of thousands of grievances that are settled by the people involved and hundreds of grievance arbitrations.

Labour law is also concerned with the relationships between unions and their members. Since collective agreements can legally make union membership mandatory, employees may need protection against their own unions. Although generally employers are free to hire at their discretion, once an employee is hired, many collective agreements (and in some jurisdictions the legislation) impose "dues shop" provisions requiring all employees within the bargaining unit to pay dues to the union, whether members or not, in return for its obligation to represent all employees in the bargaining unit equally (the Rand formula), may impose or "union shop" provisions requiring that all employees join the certified union. In some industries (eg, longshoring and construction) because of closed-shop provisions union membership is a prerequisite to being hired. These types of union security provisions have been upheld as reasonable limits to the rights guaranteed under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The common, or judge-made, law, the Canada Labour Code and the labour statutes of some provinces protect employees against unfair union disciplinary procedures and, in the case of the statutes, limit the reasons for which an employee can be expelled from a union or fired as a consequence.

The central issues of labour law are the central issues of our society. How much state regulation should exist? Can economic justice be defined and administered, or must the free market be given more play? Is there a breakdown in order as competing interests vie for public sympathy and support? Although the trend in the 1980s was towards greater regulation of all aspects of the employment relationship, including the wage bargain, the mid-1990s has seen a move towards deregulation driven by the competitive pressures inherent in globalization and the growth of free trade. Regardless, labour law continues to be a major component of labour relations and the collective bargaining system.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom