Origins

In the 17th century, the Haudenosaunee economy became interdependent with the European fur trade. They began trading with British and Dutch merchants early that century, providing animal pelts in return for iron tools, firearms, blankets and other items. Their traditional enemies, including the Huron-Wendat and Algonquin, established trading relationships and alliances with French merchants and colonists. The fur trade was intensely competitive and led to increased hostility between First Nations.

By the middle of the 17th century, the Haudenosaunee had depleted the numbers of beaver in their homeland. They therefore began a campaign to increase their territory and gain access to new hunting and trapping grounds. After Dutch traders on the Hudson River (in present day New York State) provided them with firearms, the Haudenosaunee began to exert their military strength. In 1628, they pushed the Mohicans east and, in the 1630s, the Mohawk began to raid the Algonquin in the Ottawa Valley. By the early 1640s the Mohawk and Oneida were attacking settlements of New France and raiding the colony's Algonquian allies throughout the St. Lawrence Valley.

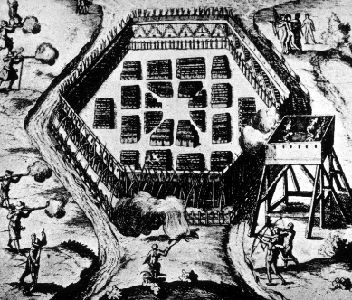

By 1642, the French had begun to halt these raids by building a chain of fortified settlements as far upriver as Montréal. The French tried to counter the Mohawk acquisition of firearms by arming their Wendat and Algonquian allies, but the Jesuits persuaded officials to restrict their sale to Christian converts, whom they saw as more “reliable.”Dispersals of First Nations

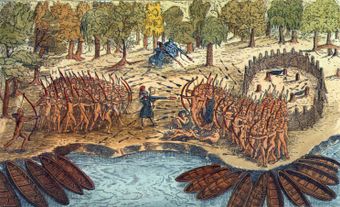

One of the profound effects of the Iroquois Wars was the dispersal of numerous First Nations. The policy of the Seneca was to disperse the Wendat, which left them free to raid the hunting peoples to the north. Their raids, beginning in 1642 with the more isolated Wendat villages, culminated in 1649 with over 1,000 Seneca and Mohawk attacking two main villages. Some Wendat tried to hold out on a nearby island but were forced to disband; some fled to Québec and others joined the Neutral, who were decisively defeated in 1651. In the winter of 1649–50 the Haudenosaunee attacked the Nipissing and the Petun.

With the Wendat nation effectively destroyed and the Neutral crushed, the Haudenosaunee increased their raids on the Mohican, Sokoki and Abenaki. While in Québec they raided as far east as Tadoussac and north beyond Lac Mistassini. Faced with stiff resistance from the Susquehannock and the Erie, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy entered into peace with the French in 1653. After concentrated Haudenosaunee attacks, the Erie were absorbed in 1657. Renewed hostilities in 1659–60 on a wide front greatly strained the confederacy, and the Haudenosaunee again sought peace with the French. But a treaty embracing all groups was not arranged until 1667, after the Carignan-Salières Regiment had burned Mohawk villages and food supplies. By 1675, the Haudenosaunee had absorbed the Susquehannock to the south and had moved westward into the Ohio Valley, where they fought the Illinois and Miami nations.

Legacy

Over the course of five conflicts, the Haudenosaunee succeeded in breaking up every one of the groups that had surrounded the confederacy. However, the victories did not bring them the prosperity they sought. The treaty of 1667 had allowed the French to extend their trade in the north and, with explorer Louis Jolliet, they advanced through the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River. As part of a broader conflict between French and British, the Haudenosaunee attacked Lachine in force in 1689 (see Lachine Raid). However, with the aid of the Troupes de la Marine, the defenders eventually forced the Haudenosaunee to make peace. In a treaty ratified July 1701 at Montréal, they agreed to remain neutral in wars between the British and French (see Peace of Montreal 1701).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom