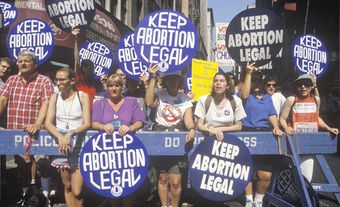

Henekh (Henry) Morgentaler, CM, abortion advocate, physician (born 19 March 1923 in Lodz, Poland; died 29 May 2013 in Toronto, ON. Morgentaler spent much of his life advocating for women’s reproductive rights at a time when they could not legally obtain abortions. He established illegal abortion clinics across Canada, challenging the federal and provincial governments to repeal their abortion laws. As a result of his campaign (and the work of organizations such as the Canadian Abortion Rights Action League, CARAL), the Supreme Court struck down federal abortion law as unconstitutional in 1988, thereby decriminalizing the procedure. Morgentaler was also the first to use the vacuum aspiration method in Canada, a safer procedure for women than previous methods.

Education and Early Career

The son of Jewish socialist activists killed in the Holocaust, Morgentaler survived Auschwitz and Dachau, arriving in Canada in 1950 (see Canada and the Holocaust). He completed his medical studies in 1953 at the Université de Montréal and began a general practice in medicine in Montreal in 1955 once he had been granted citizenship. As president of the Humanist Fellowship of Montreal, he urged the Parliamentary Committee on Health and Welfare to repeal the law against abortion in 1967. After media reports publicized his proposal, Morgentaler was bombarded with calls from women desperate to arrange an abortion. This contributed to his decision in 1969 to devote his practice to family planning. While he did perform vasectomies, insert intrauterine devices (IUDs), and provide contraceptive pills to his patients, the main purpose of his clinic was to perform abortions. (See also Birth Control in Canada; History of Birth Control in Canada.)

The First Clinics and Court Cases

When Morgentaler appeared before the Parliamentary Committee on Health and Welfare in 1967, it was illegal to perform abortions. In the same year, Pierre Trudeau, who was then Justice Minister, introduced an omnibus bill that would reform the Criminal Code. In addition to decriminalizing homosexuality, the bill also decriminalized the distribution of contraceptives and contraceptive information; the changes were approved in 1969 when Trudeau was prime minister. On the advice of the medical establishment, Section 251 of the revised Criminal Code also allowed abortions, but only in restricted circumstances. Abortions were only legal if performed in hospital, and had to be approved by a hospital therapeutic abortion committee. They could only be performed if the pregnancy posed a danger to the woman’s health or life. However, hospitals were not required to perform abortions, and access to the procedure was limited.

By performing abortions at his clinic, Morgentaler was defying the law. To draw attention to the safety and efficacy of clinical abortions, Morgentaler in 1973 publicized the fact that he had successfully carried out over 5,000 abortions. Although he was arrested and charged, a jury nevertheless found him not guilty of violating Section 251 of the Criminal Code. However, in April 1974, the Québec Court of Appeal, in an unprecedented action, quashed the jury finding and ordered Morgentaler imprisoned. Though this ruling was upheld by the Supreme Court, a second jury acquittal led Parliament to pass a Criminal Code amendment that took away appellate judges’ power to strike down acquittals and order imprisonments. After a third jury trial led to yet another acquittal, all further charges were dropped.

In 1983, Morgentaler established (still illegal) abortion clinics in Winnipeg and Toronto. Police raided both clinics shortly after they opened. In November 1984, Morgentaler and two associates — Robert Scott and Leslie Smoling — were acquitted of conspiring to procure a miscarriage (or abortion) at their Toronto clinic. The Ontario government appealed the acquittal, and the Ontario Court of Appeal ordered a new trial.

R v. Morgentaler

Morgentaler and his colleagues appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which struck down the abortion law in early 1988 on the basis that it conflicted with rights guaranteed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In particular, the Court found that the abortion law (Section 251 of the Criminal Code) violated Section 7 of the Charter. As a result, Canada had no law concerning abortion; the procedure therefore was governed not by federal law but by provincial and medical regulations. This meant that even though abortion had been decriminalized, it was not equally available to all women across the country. More than twenty years later, abortion services are particularly difficult to access in rural locations, the far north, and in much of the Maritimes. For example, abortions are not performed in Prince Edward Island, and access to abortion services is restricted in New Brunswick.

Advocacy and Legal Challenge

Morgentaler continued his campaign for women’s reproductive rights, travelling across Canada on speaking engagements and fundraising tours. He also established clinics across the country to provide abortion services and to test federal and provincial law. Morgentaler took some provincial governments to court over the closure of his clinics in those provinces, and the refusal of some provinces to fund abortions performed in private clinics. In 2003, for example, he launched a lawsuit against the New Brunswick government regarding its refusal to pay for abortions performed in private clinics (including his own). Morgentaler's actions focused attention on legal procedures as well as on the broader issues of abortion.

Retirement and Death

In 2006, Morgentaler retired from active practice, although he continued to supervise operations at his remaining clinics. He died in Toronto on 29 May 2013 of heart failure. Around the time of his death, there was considerable pressure from social conservatives and pro-life advocates to re-open the abortion debate in Canada.

Public Response

Public response to Morgentaler’s death reflected the controversy about abortion more generally. While some praised Morgentaler as a hero, others condemned him as a murderer. In the past, threats were made against his life, and his Toronto clinic was firebombed in 1992. In 2005, the University of Western Ontario awarded Morgentaler with an honorary degree, which was protested by many, including the 12,000 who signed a petition demanding the university reverse its decision. When Morgentaler was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 2008 (after several unsuccessful nominations), a number of other recipients returned their medals, including Montréal’s Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte, who had been made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1996.

Honours and Awards

- Humanist of the Year, American Humanist Association (1975)

- Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Western Ontario (2005)

- Member, Order of Canada (2008)

- Lifetime Achievement Award, Humanist Association of Canada (2008)

- Award for Outstanding Service to Humanity, Canadian Labour Congress (2008)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom