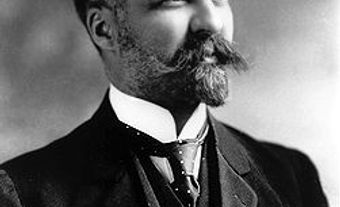

Henri Bourassa, politician, journalist (born 1 Sept 1868 in Montreal; died 31 Aug 1952 in Montreal). Henri Bourassa was an important Canadian nationalist leader who supported Canada’s increased independence from the British Empire. Bourassa was also an advocate for French Canadian rights within Canada.

Background and Political Ideology

Henri Bourassa was born on 1 Sept 1868 in Montreal. His family was one of the most prominent in Quebec; his father was a well-known painter, while his grandfather, Louis-Joseph Papineau, was a celebrated folk hero of the Rebellions of 1837. Bourassa got an early start in politics when he was elected mayor of the town of Montebello at the age of 22. Six years later, in 1896, he entered federal politics, where he stayed until 1907. Bourassa was a respected French Canadian intellectual who emphasized the need for Canada’s independence from the British Empire. He also inspired the growth of a nationalist movement in French Canada. (See also French Canadian nationalism.) Bourassa’s political vision was focused on three main themes: Canada's relationship with Great Britain, French Canadians’ place in Canada, and the values surrounding economic life.

Opposition to Canadian Involvement in the South African War

Henri Bourassa's political career coincided with a time when most Anglo-Canadians felt strongly attached to the British Empire (see Imperialism). This sentiment became particularly strong when Britain fought in the South African War, and many Anglo-Canadians felt a need to help the mother country. Bourassa, as a young and promising Liberal MP, came to prominence in October 1899 when he resigned his seat in protest. Bourassa was opposed to Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government’s decision to send volunteer Canadian troops to fight without consulting Parliament.

By 1900, he was back in the House of Commons, having won his by-election without opposition. He tried to ensure that Parliament would be the only authority that could declare war on behalf of Canada. Although his resolution was voted down, the issue would be fundamental to Canadian politics for the next 40 years.

In 1907, Bourassa resigned his seat to enter provincial politics. He was elected to the Québec Assembly in 1908 and served until 1912. Meanwhile, in 1910 he founded Le Devoir, which remains an important and influential newspaper in Quebec. He remained its editor until 1932.

Advocating for Canadian Sovereignty in the First World War

In 1910, Bourassa opposed the government's naval bill, which would have allowed the government to turn over the proposed Canadian Navy to Britain without Parliament’s permission. Using this issue, he organized an anti-Liberal campaign during the federal election of 1911. The campaign was sufficiently effective to deplete Wilfrid Laurier's electoral strength in Quebec.

After some hesitation, Bourassa came to oppose Canadian participation in the First World War. His opposition to war was mainly due to the fact that the Conservative government under Robert Borden had committed Canada’s entry into war without consulting Parliament. Such action, he feared, would strengthen the claim that Canada should automatically take part in all British wars.

Bourassa became notorious in 1917 because both major parties used him as a symbol of extreme French Canadian nationalism for their own political purposes. Laurier was unwilling to agree to conscription because he was afraid of handing over Quebec to Bourassa. Meanwhile, Borden's Union Government warned that if the Liberals led by Laurier were elected, Bourassa would be the real ruler and would take Canada out of the war. However, this was the last time that Bourassa would be a serious factor in Canadian politics. In 1925, he was again elected from his old federal constituency of Labelle and remained a member until defeated in 1935.

Despite Bourassa’s diminishing role in politics, his intellectual influence was nonetheless considerable. Mackenzie King, who replaced Laurier as leader of the Liberal Party in 1919, took up Bourassa's idea that only the Canadian Parliament could declare war. He kept Canada legally neutral for seven days after the British went to war against Germany in 1939. King thus fulfilled the program first set out by Bourassa at the turn of the century.

Bourassa’s Canadian Nationalism

Another side of Henri Bourassa's nationalist program was his insistence that Canada ought to be an Anglo-French country. In his view, French Canadian culture had to resist assimilation and gain equal rights throughout the country. He became publicly identified with what would later be called biculturalism in the 1960s. In 1905, Bourassa unsuccessfully campaigned for Catholics to control their own schools in Saskatchewan and Alberta. He warned that the equality of cultures was an important condition for French Canadians to continue accepting Confederation.

In 1912, Bourassa campaigned in favour of French education when the Ontario government sought to limit the use of French in elementary schools. (See Ontario Schools Question). He only called off his campaign in September 1916 when the pope called for moderation. However, it was not until the late 1920s that this criticized regulation was repealed.

In the early 1920s, Bourassa found his vision of a bicultural Canadian nation under attack by Québec nationalists led by Lionel Groulx. In 1922, Groulx proposed the idea of a separate Laurentian state as a desirable goal for French Canadians. Bourassa vehemently opposed this vague ideal of a separate state. The two figures represented two distinct visions of nationalism, and they clashed over which had more merit.

Bourassa’s Economic Vision

Although Henri Bourassa’s nationalist vision mainly had a political impact, Bourassa’s religious concerns were even more important to him. He believed that his people should be a beacon of light for Catholicism in North America. His greatest ambition was to prevent the Americanization of Canada, meaning to resist placing the accumulation of wealth above the worship of God in Canadian society. Although he accepted private property as essential to human liberty, he believed that in economic matters the public good should prevail.

Bourassa was much troubled by the rise of big industry. He believed that the profits of a large enterprise were immoral, but those of a small firm were legitimate. He considered small businessmen as the social class that was best prepared to conserve Catholic values. He seems to have thought that the growth of big business was due not to economic efficiency but rather to greed. If Catholic teachings were accepted, he believed that this trend might be halted or reversed.

Occasionally, he dreamed that society would revert back to being more rural and composed of small firms. This viewpoint hindered his inability to develop a realistic program to regulate the powerful influence of big businesses in economic life.

Later Life

In the 1935 election, Bourassa was defeated by Maurice Lalonde. Despite losing, Bourassa felt “relieved of a great burden and even delighted.” He retired from electoral politics for the time being. However, he would continue to occasionally give public speeches. He reiterated his vision for Canada, even though it angered many young nationalists who preferred Lionel Groulx’s vision. Bourassa also denounced the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. He did, however, show support for Vichy France, likely due to the regime’s strong Catholic influence. As in the First World War, Bourassa’s limited appetite for war drove him to support Canada withdrawing from the Second World War. In 1942, he even helped found the Bloc populaire canadien to fight against the prospect of another conscription crisis.

In 1944, Bourassa suffered a heart attack that severely limited his capacities. Finally retiring from the public eye, he died on 31 August 1952.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom