Harry Winston Jerome, OC, track and field athlete, consultant, teacher (born 30 September 1940 in Prince Albert, SK; died 7 December 1982 in Vancouver, BC). Three-time Olympian Harry Jerome won the bronze medal in the 100 m race at the 1964 Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan. He also won gold medals at the 1966 Commonwealth Games and the 1967 Pan American Games. Jerome broke the Canadian record in the 220-yard dash when he was only 18 years old and set or equalled world records in the 60-yard indoor dash, the 100-yard dash, the 100 m sprint and the 440-yard relay. Following his retirement from competition, he promoted amateur and youth sport through national and provincial programs. Jerome also advocated for better support of Canadian athletes and for greater representation of racialized Canadians on Canadian television and advertising. He was the recipient of numerous honours and awards, including the Order of Canada.

Early Life

Harry Jerome was born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, but soon moved to Winnipeg, where his father was a railway porter. He was the first of five children born to Elsie and Harry Jerome Sr.; sisters Carolyn, Louise and Valerie and brother Barton would soon follow. When he was 12, the family moved to North Vancouver, where locals tried to block the sale of the house. They were the only Black people in the community.

Record-Breaking Runner

Harry excelled at sports, including baseball, football, rugby and hockey. But he was most successful as a runner, as was his sister Valerie. In 1959, as an 18-year-old student at North Vancouver High School, Harry broke the Canadian record for the 220-yard dash set 31 years before by Percy Williams. His performance attracted the attention of the University of Oregon, which offered Jerome a scholarship to study physical education while training with its track team. (He eventually earned a Bachelor of Science degree and Master of Science degree in physical education from the University of Oregon.)

Jerome again made headlines the following year when he ran the 100 m dash in 10.0 seconds at the Canadian Olympic trials in Saskatoon in July 1960. This equalled the world record set by German sprinter Armin Hary only a month before. “Harry Jerome’s Mark Goes in Record Book,” trumpeted the Globe and Mail. The “19-year-old Vancouver sprinter became the first native Canadian to hold, officially, a world track record.”

Injuries and Criticism

Jerome and Armin Hary were considered favourites for the 100 m race at the 1960 Olympic Summer Games in Rome. However, at the games, Jerome was forced to pull up during the 100 m semifinals due to a hamstring injury. According to reports, he was so upset that he walked into the dressing room without saying a word to the press.

Reporters and officials accused him of being a quitter and suggested that he couldn’t handle the pressure of a major international competition. Hurt and angry, Jerome fought back. “I May Even Quit Canada, Says Irate Jerome” ran a headline in the Toronto Telegram on 2 September 1960. He also stated that the Canadian team should better support its athletes, including qualified medical staff at competitions. But his responses only further inflamed the press, with the Telegram stating that, “The Boy (Jerome) is Plain Nuts.” In a sports editorial titled “Jerome’s Ranting Inexcusable,” Jim Vipond of the Globe and Mail reproved the young sprinter, whom he believed “should not hide behind the immaturity of his years and unjustly criticize those who tried to befriend and assist him in his trying moments in Rome earlier this month.”

Despite the public backlash, Jerome pressed on and in 1961 tied the world record in the 100-yard dash (9.3 seconds). In 1962, he equalled yet another world record, anchoring a University of Oregon relay team that ran the 4x110-yard race in 40.0 seconds.

Jerome was therefore considered one of the top sprinters in the world when he headed to the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia. “Nobody should beat Harry Jerome in the 100 or 200 yards,” opined the Vancouver Sun on 9 November 1962. Just prior to the games, however, he developed a high fever and throat infection. In a repeat of the 1960 Olympic Games, Jerome was frustrated by injury, tearing the quadriceps tendon in his left leg. However, he didn’t at first realize what had happened, just that he had lost power. He was soon seen by two orthopaedic surgeons from Perth, who diagnosed a rupture of the rectus femoris muscle and recommended immediate surgery. Jerome opted to return to Canada for treatment.

Yet again, he was criticized in the media. Australian newspapers like the Sydney Daily Mirror accused him of quitting, while the Vancouver Sun announced, “Jerome Folds Again.” However, it wasn’t long before C.H. Wayland, general manager of the Canadian team, set the record straight in an official statement. The Globe and Mail referenced Wayland’s statement in a sympathetic article, “Canadian Athletes Understand Misfortune of Harry Jerome,” the day the sprinter returned home.

Sprinter Harry Jerome, who went to the British Empire Games determined to refute the suggestion that he quit in the Olympics, came home quietly today leaving the nightmare of a second failure behind him. Jerome came home fearing the loss of at least a year from his track career due to a thigh injury suffered in Perth.… At about the time Jerome was nearing home, Charles Wayland, commandant of the Canadian team in Perth, issued a statement that “it is essential that the true facts” be clearly stated about the sprinter’s return to Canada. “Otherwise, great and perhaps irreparable damage could be done to the reputation of a great international track and field star.” He said Jerome was hurt and did not quit.… “All members of Canada’s BEG team completely understand what happens to any athlete who has the misfortune to rupture a muscle and we all know that Jerome’s personal disappointment is even greater than ours.”

The article also informed readers that North Vancouver was holding a community-wide drive in appreciation of Jerome. Other journalists wrote in support of Jerome, as did fellow athletes such as teammate Bruce Kidd. But two questions still remained: would Jerome recover from this injury, and would he ever bring home a medal from international competition?

The Greatest Comeback

Jerome’s injury was so severe that many people thought his competitive career was over. The sprinter himself, however, believed otherwise. On 29 November 1962, four days after the race, Dr. Hector Gillespie, a Vancouver orthopaedic surgeon and team doctor for the BC Lions, employed a new technique to reattach his quadriceps muscle to his knee. The Globe and Mail reported on 1 December that Jerome was in “satisfactory condition” following the operation and on 11 January 1963 that his cast had been removed and he expected to resume training in September. Jerome missed the 1963 racing season, but sheer determination and intensive physiotherapy saw him back on the track the following year. On 28 February 1964, he ran the 60-yard dash in six seconds at an indoor meet in Portland, Oregon, equalling the world record. It was a remarkable comeback.

On the Podium

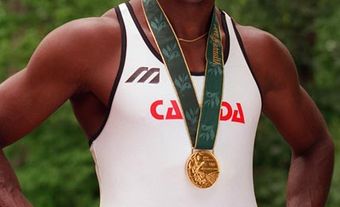

At the 1964 Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan, Jerome won bronze in the 100 m race, proving his detractors wrong. In the 200 m event, he just missed the podium, finishing fourth. “Canada’s Finest Day at Tokyo Brings Gold, Bronze Medals,” announced the Globe and Mail’s Jack Sullivan.

Canada enjoyed its finest day at the Olympics Thursday in many long years, crowned by a smashing triumph in the coxless pairs rowing event [by George Hungerford and Roger Jackson]…. Sprinter Harry Jerome of Vancouver, a disappointment at the 1960 Rome Olympics and the 1962 British Empire Games in Perth, Australia, finished a strong third in the blue-ribbon 100 metres to take the bronze medal. “I was determined to win something this time,” a happy Jerome told reporters afterward. … Jerome’s third-place finish was the best Canadian performance in the 100 metres since Percy Williams won the gold medal in 1928.… Bob Hayes of the United States tied the world record of 10 seconds flat in winning the 100 metres. Silver medallist Enrique Figuerola of Cuba was timed in 10.2, as was Jerome, whom he beat by a mere eyelash.

Accolades poured in, including congratulations from Prime Minister Lester Pearson and a telegram from John Diefenbaker stating, “Congratulations to you who have shown great courage in facing difficulties.”

Two years later, Jerome again tied the world record in the 100-yard dash, finishing the distance in 9.1 seconds. “Harry Jerome, the controversial sprinter from Vancouver, climaxed one of the greatest comebacks in sport here last night,” wrote Paul Rimstead of the Globe and Mail in July 1966. “Jerome equalled the world record of 9.1 seconds for 100 yards, held by Bob Hayes of the United States, one of the greatest achievements in the history of Canadian sports.”

Only a month later, sportswriters had more good news to report. At the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica, Jerome won gold in the 100-yard race, narrowly defeating Bahamian sprinter Tom Robinson. It took officials 42 minutes to determine the winner. According to Brian Pound of the Toronto Telegram, “When the announcement was finally made, the immobile Jerome suddenly exploded, shooting both arms in the air.” As Paul Rimstead reported, “For Jerome [the win] was important because, despite his [world] records, he has never been able to win more than a bronze medal in competition. He had a reputation of folding in the big ones.”

Jerome again reached the top of the podium at the 1967 Pan-American Games in Winnipeg, winning gold in the 100 m race. At the 1968 Olympic Summer Games in Mexico — the third Games of his career — he made it to the finals but finished seventh. He retired from international competition not long after. His last race was in 1969 at the Canadian national championships, where he beat the country’s best sprinters at the age of 29.

DID YOU KNOW?

Valerie Jerome, Harry’s sister, was also an accomplished track and field athlete. In 1959, when she was only 15 years old, she set the Canadian women’s record in the 100 metres (11.8 seconds). She competed at the 1959 Pan American Games, the 1960 Olympic Games and the 1966 Commonwealth Games.

Family

In June 1962, Jerome married Wendy Carole Foster of Edmonton, whom he had met at the University of Oregon. Daughter Deborah Catherine was born in January 1963, while her father was recovering from surgery. However, as an interracial couple, the Jeromes faced resistance and discrimination in Oregon, which put considerable strain on the relationship. They separated in 1966 and divorced in 1971. Wendy Jerome became a professor of sports psychology at Laurentian University.

Teacher, Consultant and Advocate

Jerome received his Bachelor of Science in physical education from the University of Oregon in 1964 and began teaching in British Columbia, first with the Richmond School Board (1964–65) and then with the Vancouver School Board (1965–68). In 1968, he received a Master of Science in physical education from the University of Oregon. The same year, Jerome was appointed to the National Fitness and Amateur Sport Program. He designed a series of sport instruction manuals and in 1969 led a “Sports Demonstration Tour” to high schools across Canada. In 1975, he returned to British Columbia, where he developed the Premier’s Sports Awards program.

Jerome was an important advocate for athletes, demanding better financial support, coaching and medical attention. He also became an increasingly vocal advocate for minorities. In 1979, for example, he petitioned the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission for better representation of minorities in broadcasting. Similarly, he lobbied department store chains Woodward’s, Eaton’s and the Hudson’s Bay Company to use non-white models in their advertisements.

Jerome died in 1982 as the result of a seizure at only 42 years of age. He is buried at Mountainview Cemetery in Vancouver.

Honours and Awards and Tributes

- Harry Jerome Scholarship Fund established at University of British Columbia (1962)

- BC Sports Hall of Fame (1966)

- Canadian Amateur Athletic Hall of Fame (1971)

- Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame (1971)

- British Columbia Athlete of the Century (1971)

- Officer, Order of Canada (1970)

- Harry Jerome Awards, Black Business and Professional Association (established 1983)

- Harry Jerome International Track Classic (established 1983)

- Statue of Jerome unveiled at Stanley Park, Vancouver (1988)

- Canada’s Walk of Fame (2001)

- Documentary Mighty Jerome debuts at Vancouver International Film Festival (2010)

- Harry Jerome Recreation Centre, North Vancouver, British Columbia

- Harry Jerome Sports Centre, Burnaby, British Columbia

- Harry Jerome Track, Prince Albert, Saskatchewan

- Harry Jerome Weight Room, University of Oregon

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom