The Halibut Treaty of 1923 (formally the Convention for the Preservation of Halibut Fishery of the Northern Pacific Ocean) was an agreement between Canada and the United States on fishing rights in the Pacific Ocean. It was the first environmental treaty aimed at conserving an ocean fish stock. It was also the first treaty independently negotiated and signed by the Canadian government; one of several landmark events that transitioned Canada into an autonomous sovereign state. It also indicated a shift in Canada’s economic focus from Britain to the US during the 1920s, when the US passed Britain as Canada’s largest trading partner. The treaty created the International Pacific Halibut Commission, which continues in its role today.

Self-Government but not Autonomy

The Dominion of Canada was created through an act of the British Parliament. The British North America Act, 1867 (now the Constitution Act, 1867) created self-government, a Canadian Parliament, and the position of prime minister. However, it did not grant full autonomy to Canada as a nation. Certain powers were maintained by the British Parliament; these included the right to consent, repeal, and override laws passed through the Canadian Parliament. Meanwhile, acts of the British Parliament applied to Canada.

For the negotiation of international treaties involving Canada, convention held that Britain would have a seat at the table; or at the very least, be a signatory to any agreement. Section 132 of the British North American Act concerning treaties states: “The Parliament and Government of Canada shall have all Powers necessary or proper for performing the Obligations of Canada or of any Province thereof, as Part of the British Empire, towards Foreign Countries, arising under Treaties between the Empire and such Foreign Countries.”

By the 20th century, Canada was inching towards greater autonomy from Britain. During the First World War, Prime Minister Robert Borden demanded that the Canadian Expeditionary Force fight as a single unit and not be broken up among British units. At the conclusion of the war, Borden successfully insisted that Canada represent itself at the Paris Peace Conference; be a signatory on the Treaty of Versailles; and have a its own seat at the League of Nations. In 1922, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King declined to automatically provide Canada’s military support to Britain during the Chanak Affair. Subsequent prime ministers continued this quest for autonomy.

Halibut Fishery

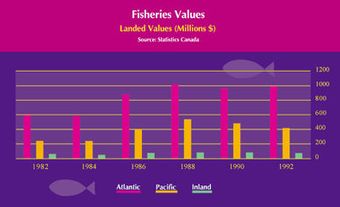

The Halibut Treaty came about as the result of depleting halibut stocks in the North Pacific, in fishing grounds shared by both Canada and the United States. ( See also Alaska Boundary Dispute.) Large scale commercial fishing of halibut began when the Northern Pacific Railway reached the West Coast; this made possible the eastward, overland transportation of fish. Demand from Europe and the US had already decimated the Atlantic halibut fishery. By 1915, the Pacific catch was more than 69 million pounds; but soon thereafter, stocks began to dwindle.

Negotiations between Canada and the US on preserving fish stocks began in 1918. The talks were a historic first, as they sought an international agreement in conservation. The result was the Convention for the Preservation of Halibut Fishery of the Northern Pacific Ocean. The treaty created a season closed to commercial fishing from 16 November to 15 February; with the penalty of seizure. The treaty was to last a minimum of five years. The agreement set in place the International Fisheries Commission (IFC). Its purpose was to “make a thorough investigation into the life history of the Pacific Halibut” and to make recommendations for the regulation of the industry.

The treaty was signed by Ernest Lapointe, Canada’s Minister of Marine and Fisheries; and by Charles Evan Hughes, the US Secretary of State. It was modest from the American point of view; but it was extremely important for Canada in symbolic terms. It was Canada’s preference not to negotiate the treaty with a British delegate at the table; nor to seek the ratification of the British Parliament.

British Reaction

The British wished to sign the treaty along with Canada, as they always had. But Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King argued that the matter was solely the concern of Canada and the US, and did not affect any British or imperial interest. Therefore, Britain should not appear as a contracting party; either in the treaty’s preamble, or as a signatory. (The treaty did, in fact, make reference to the “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland” in the preamble.)

Afterwards, Mackenzie King threatened to send a separate Canadian diplomat to Washington, DC, to represent Canada’s interests there, apart from the British ambassador. The British gave in. The Halibut Treaty precedent was confirmed by the Imperial Conference of 1923. It was an important step in establishing Canada’s right to separate diplomatic action.

The treaty signalled a shift in Canadian politics from one focused on being a part of the British Empire, to one that was more pan-Canadian. (It was sometimes described as separatist or isolationist under Mackenzie King.) It also indicated Canada’s shifting economic focus during the 1920s from Britain to the US. During this time, the US passed Britain as Canada’s largest trading partner.

The Imperial Conference in 1926 resulted in the Balfour Report. It recognized Canada and the other dominions of the British Empire as equal members of the new Commonwealth of Nations. The report put in place resolutions for independent self-government; these were included in the 1931 Statute of Westminster. That Act cut all legal ties between Canada and the British Parliament; except the power to amend the Canadian Constitution. Only in 1982 was the Constitution finally repatriated and the power of amendment transferred to Canada.

Success of the Treaty

As the IFC studied the fisheries, stocks continued to decrease. They reached a low of 21 million pounds by 1930. The IFC had developed regulations; but the original treaty did not provide the commission with the power of implementation. A revised, more wide-ranging treaty was signed on 9 May 1930. It replaced the original agreement. Further revisions were signed in 1937 and 1953; as well as a protocol signed in 1979. The IFC was renamed the International Pacific Halibut Commission. It expanded to six members and continues in its role today. The halibut fishery began to stabilize and then grow. In 1959, a catch of 71.5 million pounds finally surpassed the 1915 catch.

See also Canadian-American Relations; Continentalism; Fisheries Policy; History of Commercial Fisheries; Fisheries Research Board.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom