The trapping of animals for fur occurs in almost every country of the world. In Canada, trapping is done primarily for the cultivation of animal pelts, though some may trap for food. Pelts may be harvested through firearm or bow hunting, but the vast majority of pelted wildlife is acquired through trapping. Fur trapping is a foundational practice in both Aboriginal and European cultures in Canada, and was a primary factor in colonial activities. Economic and cultural importance, in conjunction with animal welfare concerns, had made modern trapping a contentious issue.

Traditional and Cultural Aspects

Before Europeans came to North America, trapping was an integral part of Aboriginal ways of life, providing food, clothing and shelter. The subsequent development of the fur trade, however, profoundly altered the economy. Trapping became an end in itself, to the point that extensive trapping put some species in jeopardy. Declines in the fur industry and growing concern for animal suffering have not only caused some economic and social hardships among some Aboriginal peoples, but have also impacted their way of life.

Under the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and other subsequent constitutional amendments, Aboriginal hunting, trapping and fishing rights to obtain food across all seasons on unoccupied land were guaranteed and may have precedence over provincial game laws.

Economics of Fur Trapping

In the 2009–10 season 730,915 wildlife pelts were sold in Canada — 55 per cent coming from beaver and muskrat — accounting for 28 per cent of the pelts sold in Canada; the balance coming from fur farms. Species most commonly trapped, depending on regional differences, include badger, beaver, bobcat, cougar, coyote, fisher, fox, hare, lynx, marten, mink, muskrat, otter, rabbit, raccoon, skunk, squirrel, weasel, wolf and wolverine. Bears are also trapped in some provinces.

About 70,000 people are directly employed by the Canadian fur trade. There are roughly 60,000 active trappers in Canada, including 25,000 Aboriginal people. The number of licensed trappers varies from year to year and has ranged up to 80,000 since the mid-1990s. Many trappers hold full- or part-time jobs and engage in trapping in off-duty hours and on weekends. In the 2011 National Household Survey only 465 people in Canada declared hunting and trapping to be their sole occupation. Commercial trapping is seasonally based because of the prime winter condition of the fur and because of provincial, territorial and federal trapping restrictions. Most fur trapping takes place in Québec, Ontario and Alberta, but there are also registered trap lines also British Columbia, the Yukon and Manitoba, with some covering large areas. More than 85 per cent of fur garment manufacturing takes place in Montréal.

The trapping of fur-bearing animals is licensed and regulated by provincial and territorial governments whose wildlife biologists are responsible for establishing regional management plans to ensure healthy furbearer populations. Trapping activities must be consistent with international agreements such as CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

Biological Justification for Trapping

In addition to traditional reasons for trapping, the practice may also help manage certain biological phenomenon. Biological justifications for trapping have been predicated on the desirability of controlling population numbers if starvation and habitat damage are to be avoided; on the danger of diseases in wildlife populations like sarcoptic mange and canine distemper; and on the danger of diseases like rabies and tularemia being communicated to domestic animals or humans. Any attempt at alleviating these concerns involves factors that are difficult to estimate.

Well-defined 10-year population cycles — where populations rise and fall in a specific pattern over a period of time — have been observed from Canadian fur-trapping returns for coyote, snowshoe hare, mink, fisher and marten. Canadian lynx and red fox cycles span the past 200 and 100 years respectively, but the causes of these cyclic changes are unclear. Reproductive rates in animals like the beaver and muskrat may actually rise in response to trapping. Trapping of particular species may be based on the economics of fads and fashions; the rarest species may become the most sought after. Non-target catches (including some pets) may comprise at least 10 per cent of the total land-trapped animals but a lesser percentage of the semi-aquatics. Thinning out a population may or may not reduce disease incidence; in some areas where the leg-hold trap has been banned, there have been no observable increases in diseases.

Ethical Concerns

The continuing development of attitudes towards animals in Canada has involved concerns for humane treatment in trapping activities, as well as the fundamental opposition to trapping on philosophical grounds. Targets for humane treatment advocates have included seal hunting, which has sometimes involved live skinning; trapping, where animals may suffer for prolonged periods; and the food industry, where animals may be housed in cramped and inhumane conditions, and where slaughter may induce fear, stress, suffering or panic. Philosophical opposition is based in consistent moral and ethical positions that no animal should be needlessly abused or exploited.

The conceptual thrust of the animal rights movement is in direct opposition to the pursuit of fur trapping. Also, as with the seal hunt, growing concern in Europe and elsewhere about the lack of humaneness in North American trapping may, considering Canada's heavy dependence on the export market, decisively influence the continuance of Canadian fur trapping. As animal rights groups raised concerns about the fur industry's practices, pelt production fell by 62 per cent in the early 1990s, and the industry continued to struggle in the 2000s before seeing a resurgence in the early 2010s.

Trapping Methods and Policy

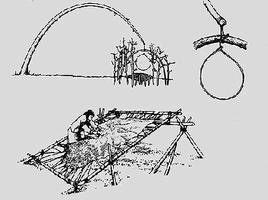

Traps are for holding (foot snare, leg-hold, box) or killing (deadfall, neck snare, Conibear, submarine trap). Box holding traps are cumbersome to transport and may cause stress, but they are normally non-injurious. Some species caught in a leg-hold may bite off a limb or limbs ("wring-off") to escape, unless the trap has a "stop-loss" device. As of 1986 steel-toothed, leg-hold traps were still manufactured in the United States but were banned in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia.

The neck snare may slowly choke the animal to death, as it struggles to escape, or catch around other parts of the body — it can cause gross injuries and protracted suffering. The Conibear trap may not kill quickly if the animal enters it incorrectly or if the closing impact is insufficient. If traps are not visited regularly, animals may suffer from exposure, stress, thirst, starvation, gangrene and predation. Only British Columbia, Ontario, Alberta, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island require visitation every one to three days. To avoid bullet holes in the pelt, a trapper dispatches an animal by clubbing its head, by using a snare on a handle to choke it, or by stamping on its chest.

The Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals (APFA) and the Canadian Association for Humane Trapping (CAHT) have been influential in informing the public and governmental officials about the ethical issues and suffering involved in trapping; in sponsoring research on the development of more humane traps; and in advocating the withdrawal of inhumane traps. For example, leg-hold traps are now banned as land sets for a number of species in British Columbia and Ontario.

CAHT joined with the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies to form the Humane Trap Development Committee (HTDC). The HTDC definition of a humane death is that the animal suffers neither panic nor pain. The Fur Institute of Canada (FIC), formed in 1983, is a private corporation funded primarily by the federal government. Its purposes are dissemination of information to the public on behalf of the fur industry and humane trap research and development.

As early as 1986, federal government committees and departments have sponsored papers outlining possible ways of defending the fur trade against anti-fur activists, often using the issue of Aboriginal rights as a centrepiece, emphasizing Canada's historical dependence on the fur trade and claiming that trapping maintains nature's balance. Organizations like the Aboriginal Trappers Federation of Canada (ATFC), founded in 1985, have likewise lobbied both domestically and internationally for fur trapping as an essential aspect of Aboriginal rights.

The Criminal Code of Canada (s402(1)a) states that "Every one commits an offence who wilfully causes or, being the owner, wilfully allows to be caused unnecessary pain, suffering or injury to an animal or bird"; but there is no precedent for it being applied on behalf of wild animals in trapping. A private member's bill (C-208) to amend the Criminal Code in favour of humane traps led to evidence being presented in 1977, but the bill was not adopted.

Advancement of Trapping Technology

From 1985 to 1993, in cooperation with the Alberta Environmental Centre and the Alberta Research Council, the Fur Institute of Canada funded an extensive research program that resulted in the development of effective research protocols and the development of humane trapping devices for several furbearers. Many of these traps have been used as alternatives to controversial and inhumane steel-jawed foothold traps. Further research and development work has been conducted since 1993 by Alpha Wildlife Research & Management Ltd, an impartial research corporation which also organized a unique international mammal trapping symposium in 1997, and since then has published information on mammal trapping technology and ethics.

An Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS), signed by Canada and the European Union in December 1997, was implemented in Canada in the fall of 2007. The agreement requires that wild furs be taken in accordance with scientifically verified and internationally accepted humane systems. However, international standards failed to completely incorporate technical advances, and the United States developed its own best practices on the basis of technical, economic and social criteria. Nevertheless, criteria for performance of humane traps consistent with technological development have been identified by wildlife professionals: humane killing traps should render at least 70 per cent of target animals irreversibly unconscious in less than 3 minutes; and humane live traps should hold at least 70 per cent of animals without serious injuries.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom