Throughout the period of the historical fur trade (early 17th to the mid-19th century), water routes were the natural “highways” of First Nations trappers and European fur traders. Water trading networks connected Indigenous societies from the Atlantic Ocean, along the St. Lawrence River to the Great Lakes, and then on towards the Hudson Bay watershed. North America’s waterborne geography facilitated intracontinental travel, enabled European expansion and settlement into Indigenous North America, and shaped the contours of Euro-Indigenous relations in the context of the fur trade. These extensive and interconnected systems of rivers, lakes and overland trails criss-crossed Indigenous territories and had been used for generations. At the height of the fur trade, the principal canoe route extended westward from the Island of Montreal through the Great Lakes, and from the northwestern shore of Lake Superior over the height of land into the Hudson Bay watershed. From the Lake Winnipeg basin, Indigenous trappers and European traders fanned out towards the Western Prairies via the Assiniboine, Qu’Appelle and Souris rivers, towards the foothills of the Rocky Mountains via the North and South branches of the Saskatchewan River, and finally towards the Athabasca Country via the Sturgeon-weir River and the Methye Portage.

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin

For Europeans who ventured westward across the North Atlantic Ocean, the two main gateways to the North American fur trade were the St. Lawrence River and Hudson Bay. New France carved out a vast commercial empire based on the fur trade by navigating the lakes, rivers and portages that knit together the vast interior maritime region of North America. From the Atlantic coast, the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River led the French westward through the Great Lakes, to the Mississippi valley, to Hudson Bay and James Bay, and eventually to the Lake Winnipeg basin and beyond. From their settlements of Quebec and Montreal, the French initially tapped a vast reservoir of furs from the St. Lawrence River and its tributaries, including the pelts originating from the Saguenay River, Lac Saint-Jean and the Mistassini River from the lower St. Lawrence. Additionally, pelts entered the St. Lawrence via the Ottawa River, which originated as far to the northwest as Lake Timiskaming, the Abitibi River and James Bay.

Most important to the later trade was the main “voyageur highway” the French developed to the west via the St. Lawrence, Ottawa, Mattawa and French rivers to Georgian Bay on Lake Huron. By the 1740s, the French had extended the voyageur highway to the head of Lake Superior and thereafter to the vast fur reserves of the Hudson Bay watershed. After the conquest of New France in 1760, this route was adopted by English, Scottish, American and French Canadian pedlars from Montreal and then by the North West Company (NWC). The route inland from Lake Superior to the Hudson Bay watershed began at Grand Portage (later Fort William at the mouth of the Kaministiquia River following the Jay Treaty of 1794). It twisted north and west through a series of rivers and lakes marked by more than 50 tortuous portages. From Lake Winnipeg, the traders headed west via the two branches of the Saskatchewan River. Many went northwest via Methye Portage, which connected Lac La Loche to Clearwater River, and then to Lake Athabasca. From the Athabasca Country, the fur trade extended down the Peace, Slave and Mackenzie rivers.

The Hudson Bay Watershed

Hudson Bay was the second main gateway to the furbearing animals of the boreal forests and the great herds of bison on the northern plains. The London-based Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) accessed these rich territories of the western interior by such avenues as the Churchill, Nelson, Hayes, Severn and Albany rivers. From its foundation in 1670 until the establishment of its first inland post in 1774 with the construction of Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River, the HBC’s official policy was to build its factories (trading posts) on the rim of Hudson Bay and wait for First Nations to bring furs to them.

The HBC began to move inland in 1774 in response to competition from the highly organized Montreal pedlars and, later, the NWC. Most of the HBC’s traffic inland was via the Hayes and Nelson rivers. Three tracks led from the interior to HBC headquarters at York Factory: the Upper, Middle and Lower Track Routes. The Upper Track started at Cumberland Lake, up the Sturgeon-weir River, up the Goose River and over the Cranberry Portage, then down the Grass River to the Nelson River at Split Lake. The Middle Track began on the lower Saskatchewan, down the Summerberry River and up into Moose Lake, and then down the Minago River to Cross Lake, before joining the Hayes River. The Lower Track started near the mouth of the Saskatchewan River at Grand Rapids, continued across the top of Lake Winnipeg, and then down the Hayes River. Whichever track route HBC traders followed, the Hayes-Nelson watershed was the gateway to the western interior and connected Hudson Bay to Lake Winnipeg, the Red River Valley, the north and south branches of the Saskatchewan, and the Northern Great Plains.

In the direct competition that ensued between the HBC and other traders, the rivals paced one another westward across the Prairies. Eventually, the routes proceeded via the Howse, Athabasca and Yellowhead passes through the Rocky Mountains and down the Columbia River to the Pacific. After 1814, HBC ships rounded Cape Horn to service Pacific posts by sea.

Indigenous Agency

Recent historical scholarship has correctly framed many of the great European explorers of the fur trade – like Henry Kelsey, Anthony Henday, Samuel Hearne, Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye – more as passengers than as pathfinders. If not for the co-operation and goodwill of First Nations, it is unlikely that these European newcomers (as intrepid as they were) would have successfully navigated the complex waterborne and land-based routes of the fur trade that criss-crossed North America.

Indigenous peoples, not Europeans, dominated the trade route networks of North America. The geopolitical and commercial significance of these inland waterways and overland trails cannot be overstated. Access to and control of these trade routes could mean subsistence or starvation and life or death for many First Nations.

In the early 17th century, Innu, Algonquin and Wendat peoples struggled to control trade routes leading to French trading stations along the St. Lawrence River. To the northwest, Cree and Nakoda (Assiniboine) peoples, who secured early access to HBC trade, used iron weapons and guns to push against the Dene, Inuit, Dakota, Aaniiih (Gros Ventre) and Niitsítapi (Blackfoot) to expand their territories and to secure their position as middlemen along fur trade routes. Further west, the Niitsítapi blockaded Howse Pass to prevent NWC personnel from crossing the Rocky Mountains to trade with and arm their enemies, the Ktunaxa (Kootenay) and Salish. (See Interior Salish, Coast Salish, Northern Coast Salish and Central Coast Salish.)

Portages

Portages, or "carrying places" as the English traders called them, served to knit the waterborne routes of the fur trade together. Portages were places where canoes and cargo needed to be carried overland to avoid waterborne hazards, like rapids, rocks and dangerous currents, or to reach the next navigable body of water. Portages were built and maintained by Indigenous peoples for generations prior to the arrival of European colonizers.

The major portages of the Canadian fur trade were the Grand Portage, Frog Portage (Portage du Traite) and Methye Portage (Portage La Loche). Geographically speaking, these portages were significant because they demarcated boundaries from one major watershed to another. Grand Portage bridged the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin with the Hudson Bay watershed; Frog Portage linked the Saskatchewan and Churchill basins; Methye Portage connected the Churchill River waterways to the Athabasca Country, the Mackenzie River basin and the Arctic watershed.

These major portages were sites of commercial, social and spiritual significance to Indigenous travellers and European traders. At important portages that demarcated the boundaries of watersheds, French Canadian voyageurs performed and participated in ceremonies and rituals of mock baptism on novices, a rite of initiation to mark the symbolic passage to different worlds: the transition from one drainage basin into another.

Transportation Technology

European travellers and traders relied heavily on Indigenous technological, environmental and geographic knowledge to navigate the landscapes and waterways of the fur trade. The birchbark canoe, an ingenious First Nations technology, which ranged from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Hudson Bay watershed, was designed to be both lightweight and easily repairable while travelling. In short order, European newcomers appreciated and adopted the birchbark canoe as the best means of transportation for navigating the intertwined waterways of the fur trade world. The birchbark canoe was well-suited for navigating Canada’s lakes and rivers because it handled easily in rough water, was light enough to portage, could carry several times its weight in cargo, and could be repaired anywhere where birchbark was abundant.

In general, two types of canoes were used to navigate the fur trade routes: the canot du maître, a large freight canoe that carried trade goods and furs between Montreal and Grand Portage on Lake Superior, and the canot du nord (north canoe), a smaller, canoe that carried the trade over the smaller lakes, rivers and streams of the Northwest. Conversely, the HBC adopted the York boat as their inland freight-carrying vessel, which became the main mode of transportation between York Factory on Hudson Bay and inland trading posts from the 1820s until the advent of steamboats on Lake Winnipeg in the 1870s.

Strategic Sites

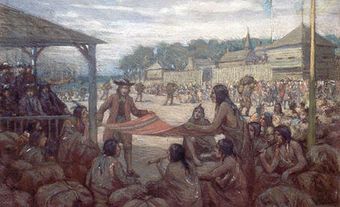

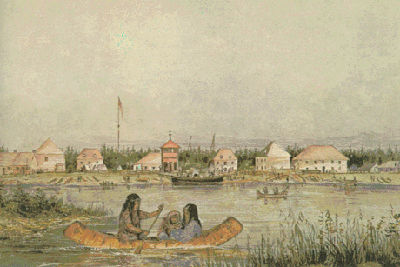

Indigenous villages and the trading posts that dotted the Canadian trade route network were usually established side-by-side, since the location of a trading post depended on the presence of Indigenous peoples willing and able to trade. As a result, important portages and the nexuses of major trade routes became vital centres of settlement and seasonal aggregation where Indigenous peoples and Europeans alike congregated for commercial, spiritual, social, diplomatic and subsistence purposes. For example, the site of Baawaating (Sault Ste. Marie), where the turbulent St. Marys River links the Great Lakes of Superior and Huron, had a permanent Anishinaabe village, a seasonal visitation of various Anishinaabe clans to fish at the Sault (rapids), housed a Jesuit mission and numerous fur trade posts, and now is the site of the twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

For another example, the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers has been a First Nations meeting place for over 6,000 years and was the site of a long list of European trading posts, including Fort Rouge (French run), Fort Gibraltar (NWC), and Fort Garry (then Upper Fort Garry after the HBC-NWC merger of 1821). To a large extent then, European trading posts as well as future settlements were determined by existing Indigenous social geography.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom