Between 1840 and 1930, nearly a million francophones from Canada emigrated to the United States. (See also Canada and United States.) Most emigrants came from Quebec. There were also Acadians from the Atlantic provinces. These emigrants lived throughout the Northern US, but most settled in New England. The largest cohort worked in the textile industry. The 1880s and 1890s were the crest of several waves of emigration that ended with the Great Depression. Also known as Franco-Americans, about two million French Canadian descendants live in New England today.

Causes of Emigration from Quebec

Historians tend to agree that most French Canadian emigrants were people from the poorer classes of rural Quebec in search of jobs. However, historians differ about the underlying economic causes of the emigration movement.

Some historians argue that an agricultural crisis in 19th-century Quebec drove this movement. They attribute the crisis to the division of family farms as the population multiplied. A lack of arable land and poor agricultural methods, they argue, exacerbated the crisis. Increasingly, indebted farmers emigrated in search of cash. They intended to return to Canada eventually to shore up the family farm or to purchase land.

Other historians argue that increased competition from farms in western North America influenced family farmers in Quebec to specialize. Some farmers had to retool their operations to concentrate on specialties like dairy farming or fodder crops. The need to re-equip their farms to compete drove farmers into debt. This increasingly competitive rural economy put economic pressure on poorer farmers, day laborers and wage earners. Many emigrated to the US in search of steady work. (See also Agriculture and Food; Agriculture in Canada.)

French Canadians in New England (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut) had numerous occupations. However, most worked in the US textile industry. Textile manufacturing flourished in early-19th-century New England. But the US Civil War disrupted the cotton industry. (See also American Civil War and Canada.) After the war, the textile mills faced a severe labour shortage. Manufacturers increasingly turned to Quebec for labour.

Recruiters brought entire families from Quebec to New England to work in the mills. Men, women and children alike worked in them. Women’s participation in the industrial labour force made “cotton mill operative” the most common occupation for French Canadians in New England by 1900.

What had been a small, migrant and mostly male emigration before the American Civil War became a mass movement. By 1900, 10 per cent of the population of New England was French Canadian.

Little Canadas

Between 1865 and 1900, French Canadians in New England formed their own neighbourhoods in the industrial towns where they settled. These neighbourhoods were often called “Little Canadas.” French Canadians had their own churches and schools. These communities also had their own businesses and sometimes a French-language newspaper. Within these communities, French Canadians preserved their language, religion and customs. (See also French Language in Canada; Catholicism in Canada.)

Well-known figures of the period, including Métis leader Louis Riel, Quebec politicians Honoré Mercier and Henri Bourassa, and clergyman/historian Lionel Groulx, visited the Little Canadas of New England and spoke publicly there. Journalist and Montreal mayor Honoré Beaugrand and composer Calixa Lavallée (see “O Canada”) lived in French Canadian New England for parts of their lives.

In some towns, such as Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and Biddeford, Maine, French Canadians were the majority of the population by the early 20th century. These French Canadian enclaves numbered in the tens of thousands. Other New England communities with French Canadian populations on the same scale in 1900 were Lewiston, Maine; Manchester, New Hampshire; and the Massachusetts towns of Fall River, Lowell, Holyoke, Worcester and New Bedford.

Reception of French Canadians in the US

Factory owners benefited from the presence of French Canadian workers. However, some in the US regarded them with hostility and suspicion. The Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor published a report on the subject in 1881. The bureau dubbed New England’s French Canadians “the Chinese of the Eastern States.” This report appeared one year before the US Congress placed restrictions on Chinese immigration, amid considerable anti-Chinese racism. (See also Chinese Head Tax in Canada; Anti-Asian Racism in Canada.)

In the 1880s and 1890s, some elements in the US press suggested that the Catholic Church had sent French Canadians to New England in a bid to revive New France. This conspiracy theory alleged that French Canadians sought to seize political control of New England. Quebec would then become an independent country and annex the Northeastern United States to a newly independent nation called New France. Protestant churches in the US responded to these allegations with well-funded efforts to convert Catholic French Canadians. In the early 20th century, the eugenics movement and the resurgent Ku Klux Klan targeted New England’s French Canadians.

However, other voices defended French Canadians in the press. The Little Canadas persisted. Factory owners continued to hire French Canadian labour in significant numbers until the Great Depression.

Franco-American Elites

Journalists, professionals, business owners and priests constituted a small French Canadian elite in the US in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eventually, US voters elected a handful of French Canadians to high office. Aram Pothier served as Governor of Rhode Island. Hugo Dubuque was a Massachusetts state legislator and presided as a Superior Court judge.

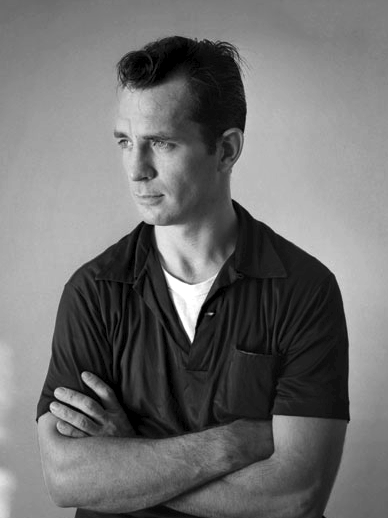

Some French Canadian emigrants and their children saw success in the US in a variety of fields, including business (Tom Plant), firearm design (John Garand, né Jean-Cantius Garand), literature (Jack Kerouac; Grace Metalious, née Marie Grace DeRepentigny), sports (Napoleon Lajoie) and music (Eva Tanguay, Rudy Vallée).

However, the majority of New England’s French Canadians in the 20th century worked in industrial jobs or trades. Many of their descendants continued to do so for several generations.

Decline of the Little Canadas

The year 1923 represented the peak of cotton textile manufacturing in the US, followed by a slow decline. As it peaked, the industry’s centre gradually moved from New England to the American South. The textile industry took advantage of lower labour costs and the lack of unionization in that region.

In 1930, the Great Depression led to changes in immigration rules at the Canada/US border. (See Immigration Policy in Canada.) These policies ended the era of French Canadian emigration to New England. The Great Depression saw many New England factories close permanently.

The decline of New England’s industrial base continued throughout the mid-20th century. As the factories where French Canadians worked disappeared, the Little Canadas gradually dissolved. As these neighbourhoods dispersed, the institutions that French Canadians established to sustain their language and culture in New England waned.

Franco-Americans Today

Among the more than two million French Canadian and Acadian descendants in New England, some continue to claim a distinct identity. Today, they are sometimes known as Franco-Americans. There are university programs, publications, local social organizations, genealogical societies, books, blogs and podcasts dedicated to their history and contemporary situation. Today, most French Canadian and Acadian descendants in the US speak English. Their 21st-century identity claims are based not on language but on shared history and experience, as well as family and community ties.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom