Exports are goods or services that residents of one country sell to residents of another country. Since its earliest days, Canada’s economic prosperity has relied on exports to larger markets; first through its colonial ties to Britain and later due to its geographic proximity to the United States. Billions of dollars of goods and services cross Canada’s border each year. (See International Trade.) Exports make up about a third of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP). In 2019, Canadians exported $729 billion worth of goods and services. Almost 75 per cent of Canada’s total exports go to the United States. (See Canada-US Economic Relations.) Other major markets include the European Union, China and Japan.

Key Terms

Trade balance The difference between what a country sells to other countries and what it buys from them. If a nation sells more than it buys, it has a positive trade balance — a trade surplus. If a nation buys more goods and services than it sells to other countries, it has a negative trade balance — a trade deficit.

Canada’s Major Exports

In 2019, Canada’s top three exported goods were energy products (worth $114 billion); motor vehicles and motor vehicle parts ($93 billion); and consumer goods ($71 billion). These three categories made up almost half of all exports. Canada’s exports saw a sharp decline during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent border closures in 2020; they were expected to grow again as the world economy gradually reopened.

Canada’s major services exports include commercial services; travel services (see tourism); transportation; and government services. Commercial services, which make up the largest proportion of services exports, is the only category that has regularly had a trade surplus for the last decade. Some commercial services exports include financial services; information technology; research and development; and business management.

Canada’s trade deficit widened in the last half of the 2010s. This was due to exports in goods lagging behind imports.

History and Debates

Historian Michael Hart has noted that Canada’s exports have historically been resource-based and at a low level of processing. This started with fur and fish before moving to wheat and forestry, finally graduating to metals and minerals. These resource exports were sold in world markets in exchange for money, food, consumer goods, and machinery.

In the early mercantilist era, colonial powers viewed trade as a zero-sum game; imports indicated dependency and weakness while exports indicated independence and strength. Colonies sent raw materials to the home country, which then turned them into finished goods for consumption. As a result, Canada became overly dependent on exporting certain key resources — or staples — rather than developing a more diversified economy or local industries. (See also Staple Thesis.)

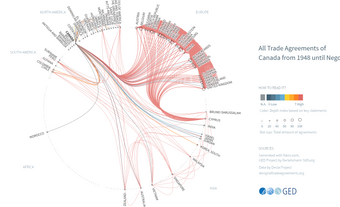

In the 19th century, Canadian development continued along these lines. The country exported resource-based products and protected its own manufacturers from foreign competition. (See National Policy.) By the 20th century, however, Canada had developed a strong domestic manufacturing sector. By mid-century, it had signed a series of free trade agreements; most notably, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1948 and the Automotive Products Trade Agreement (the Canada-US Auto Pact) in 1965. (See International Trade.)

The Auto Pact led to the integration of the Canadian and US automotive industries into a shared North American market. Auto parts became one of Canada’s largest categories of exports abroad. More than 100,000 jobs were created in the automotive industry in Canada by 1980, in addition to a comparable number of jobs across related industries. The Canadian and US economies were further integrated with the signing of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) in 1989; it became the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the addition of Mexico in 1994. Canada is now party to 15 free trade agreements in force. These include the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), which replaced NAFTA on 1 July 2020.

Significance

Exports are generally viewed as positive for the Canadian economy. They generate less political debate than the much more contentious issue of allowing foreign companies to access Canadian markets. (See Foreign Investment; Multinational Corporation.) However, disputes arise when other nations place restrictions on Canadian exports. Examples include the longstanding softwood lumber dispute between the United States and Canada; as well as US tariffs placed on Canadian steel, aluminum and lumber during the CUSMA negotiations.

Contemporary debates on export policies often focus on reducing Canada’s dependence on the United States for exports and the need to find new markets; on preserving and upholding an effective international trade system; and on increasing the competitiveness of Canadian exporters in the global marketplace.

See also Imports to Canada; Balance of Payments; Free Trade; International Trade; Economics; International Economics; Industrial Strategy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

_IMO_9785756,_Maasmond_pic.jpg)