Electoral systems are methods of choosing political representatives. (See also Political Campaigning in Canada.) Elections in Canada use a first-past-the-post system, whereby the candidate that wins the most votes in a constituency is selected to represent that riding. Elections are governed by an elaborate series of laws and a well-developed administrative apparatus. They occur at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal levels. Canada’s federal election system is governed by the Canada Elections Act. It is administered by the Chief Electoral Officer. Provincial election systems, governed by provincial election acts, are similar to the federal system; they differ slightly from each other in important details. Federal and provincial campaigns — and that of Yukon — are party contests in which candidates represent political parties. Municipal campaigns — and those of Northwest Territories and Nunavut — are contested by individuals, not by parties.

Historical Background

Canada is a constitutional monarchy. The head of state is the British monarch. They are represented by the governor general at the federal level and by a lieutenant-governor in each province. (See also Crown.) Representative political institutions were established in the British North American colonies of Lower Canada, Upper Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick before the end of the 18th century. (See also Nova Scotia: The Cradle of Canadian Parliamentary Democracy.)

Until responsible government was established in the mid-19th century, the governor of each colony, as the appointed representative of the British Crown, frequently intervened in electoral campaigns; they ensured the election of members who would co-operate with them and make the necessary funds available to their administration. Once responsible government was achieved, recognized government officials and opposition leaders attempted to coordinate the campaigns of their followers. The goal was to elect as many of them as possible.

Early election campaigns were largely a series of individual efforts in local constituencies. (See Local Government.) Unlike their modern counterparts, early elections did not lead up to a single polling day; they were spread over several weeks. Different ridings voted on different days. This enabled the government to schedule the polling in its safest ridings at an early date. This created a bandwagon effect that might persuade voters in more doubtful ridings to support the incumbents. Opposition strongholds were left to the last so as not to discourage supporters of the government. Party leaders and other notable figures often were candidates in more than one constituency. This increased their odds of retaining a seat. (See also Voting in Early Canada.)

Within each riding, voting might extend over two days. Voting was by a show of hands rather than by secret ballot; bribery and intimidation were therefore a common and more-or-less accepted aspect of campaigns. (See Political Corruption; Conflict of Interest.) The small size of the electorates facilitated a more personal approach to campaigning than is possible today. In the federal election of 1867, an average of fewer than 1,500 votes was cast in each constituency.

With Confederation in 1867, campaigns had to be extended over a vast geographical area. The general election campaigns of 1867, 1872 and 1874 were conducted in a highly decentralized manner. They largely followed the rules and practices that the various provinces had inherited from pre-Confederation days. The first national election provisions were enacted in 1885. This laid the foundations for the present system. Canada’s electoral process is now national; the same basic rules are in force throughout the country.

Voting in Canada

Until 1918, only men over the age of 21 had the right to vote in Canada. Even then, only those who met a property qualification were able to do so. Over time, the right to vote has become more universal. It has been expanded at times by Parliament in response to social pressures and at other times by courts interpreting the right to vote as it is expressed in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. (See also Voting Rights Collection.) Now, subject to only a very few special constraints, any Canadian citizen at least 18 years old may vote. (See also Human Rights; Women’s Suffrage.)

Generally, a person’s name must appear on an official list of voters to vote. Since the 1997 federal election, elections have been conducted from a permanent electoral register. It is maintained and updated on a regular basis.

Election campaigns once took about 60 days. Party leaders often travelled by train. The list of electors took considerable time to compile. Enumerators went from door to door compiling a list of people entitled to vote. The elimination of the need for door-to-door enumeration reduced the length of a federal election campaign to about 36 days. It also saved $60 million between the 1997 and 2004 elections. From 1982 to 1993, elections had to be at least 50 days long. In 1996, the law required that a campaign be at least 47 days long.

How do Elections in Canada Work?

Election Administration

Elections Canada is the independent and non-partisan agency that is responsible for administering federal elections. One of its duties is to keep the electoral system under continual review, with improvements constantly in mind. Elections Canada is headed by Canada’s Chief Electoral Officer. They have authority over the operation of a federal election. Authority in each constituency is vested in a returning officer. They are appointed for 10-year terms by the chief electoral officer. New returning officers must be appointed following any redistribution or significant readjustment of existing electoral district boundaries. (See Redistribution of Federal Electoral Districts.)

Calling an Election in Canada

The Constitution Act, 1982 requires that no more than five years pass between elections. Election writs — formal written orders to begin an election — are issued by the governor general; or the lieutenant-governor at the provincial level. This is normally done at the request of the prime minister or premier.

Canada’s Constitution requires that elections be held at least every five years; but the convention is that they be held every four years. In 2007, Parliament passed a law establishing fixed election dates. Under this law, elections are to be held on the third Monday in October in the fourth year following the last federal election. There are, however, exceptions to this, particularly with minority governments and during wartime.

The governor general retains the power to dissolve Parliament. This power is exercised in consultation with the prime minister. This means that it is not difficult for a prime minister to override the fixed election law, as was done in 2008. If a prime minister and her or his government loses the confidence of the House of Commons (as happened in 2011), the prime minister may request that the House of Commons be dissolved and an election be called. This process is colloquially known as “dropping the writ.” It is completed each time an election is called. Under exceptional circumstances, the Crown can reject the prime minister’s advice. (See King-Byng Affair.)

In situations where a Member of Parliament (MP) vacates a seat between elections, a by-election is called to hold an election for that single seat.

Election Day

Canadian voters go to the polls on the same day across the country. Hours of voting are meant to be extensive enough to give people a reasonable opportunity to vote. In fact, employers are required by law to ensure that their employees have three consecutive hours to vote on election day. Polling stations across the country are open for 12 hours on election day. However, the six different time zones in Canada have caused dissatisfaction in the Western provinces. Because more than two-thirds of the seats are in Eastern Canada, media coverage often declares the election over before the polls have closed in British Columbia. (See Time Zones and Legal Time.)

Since the 1997 election, voting hours have been staggered across the country so that the polls close at about the same time everywhere. There is now only a three hour gap between the closing of the polls in Newfoundland and Labrador and the closing of the polls in British Columbia. Until 2014, it was illegal to transmit election results until the polls had closed everywhere in Canada. However, advances in communication technology rendered this provision almost impossible to enforce. It was repealed in 2014.

In the past, voting was largely restricted to polling stations on election day. There were advance polls; but the expectation was that these were for people who would be unable to go to the polling station on election day. Now, there are a variety of ways for people to vote. These are available to anyone who wishes to use them. Besides voting on election day, there are four days of advance voting; this starts 10 days before the election. In addition, voters can cast a ballot at their local Elections Canada office, or satellite office, for most of the campaign period. Finally, voters can request a special ballot and vote by mail.

Advance and special ballots are not counted until the polls have closed on election day. This is done to keep voters from being influenced on the main polling day. Candidates or their representatives may be present in the polling stations to witness the votes being cast and to ensure the honesty of the count.

Party System and Candidates

Though Canadian elections select individual MPs, they rely heavily on political parties. (See Canadian Party System.) Political parties nominate candidates; plan and finance campaigns; select the issues over which each election is fought; and provide the leader who, each party hopes, will become prime minister or at least leader of the Opposition. (See also Leadership Convention.)

With some exceptions, and after complying with certain legal requirements, any voter may also be a candidate. Because most candidates are judged by their party affiliation rather than by personal qualifications; so, the only candidates with any real chance of being elected are those affiliated with an official party. It is not impossible for independent candidates to get elected to Parliament; but it is unusual. Because of the importance of political parties to the electoral process, they are increasingly subject to state regulation, even though they are private entities. This is particularly true of parties’ and candidates’ financial activities; but the limits on both parties and candidates are generous. (See Political Party Financing in Canada.) Since the 1972 election, the candidate’s party has appeared following his or her name on the ballot.

The procedures by which parties nominate their candidates are determined by the parties themselves. However, the financial arrangements of the process are regulated. Nomination contestants are subject to financial disclosure laws; they must limit their spending on the contest to no more than 20 per cent of the spending limit for that constituency in a federal election. The Canada Elections Act, which governs the financing and running of elections, is administered by the Chief Electoral Officer.

Constituencies

Canada is divided into 338 single-member constituencies, or “ridings.” The number was increased from 308 in 2011. (See Redistribution of Federal Electoral Districts.) Voters may vote only in the constituency in which they have been enumerated and for one of the candidates running in that constituency. The constituencies are divided into different polling divisions. Each division has about 250 to 450 electors. Voters must cast their ballots in the polling division where their names are registered.

Determining Who Governs: Plurality and First Past the Post

Some parts of the world have very complicated voting systems. Canada’s, known as the plurality system, is very simple. Voters in each constituency choose from among the candidates who want to represent that constituency as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons. The candidate who receives a plurality of the vote — more votes than any other candidate, but not necessarily a majority of the vote — wins the election in that constituency and the right to serve as its MP. This method is often referred to as “first past the post.” The winning candidate in a riding in which only two candidates run must have a majority of the votes cast; but a candidate among three or more in another constituency may be elected with far less than the 50 per cent of the vote that would constitute a true majority.

Voters choose an MP to represent their constituency; they do not directly vote for the party or leader they want to see forming government. The party leader with the support of the most MPs can become prime minister. If a majority of the MPs come from one party (at least 170 seats out of 338), that party leader automatically becomes prime minister. He or she then appoints members to Cabinet. It is the effective Government of Canada.

In cases where no party wins a majority of the seats, the outcome of the election is less clear. Most common in Canada is a minority government. This is when a party — usually the one with the most seats — governs without commanding a majority. Such arrangements typically require the tacit support of another party or parties. For example, from 1972 to 1974, the Liberal Party formed a minority government with the support of the New Democratic Party. The other scenario is a coalition government, in which MPs from more than one party take cabinet posts. Coalition governments are common in many parliamentary democracies. They are very rare in Canada.

The creation of majority governments is one of the features of the single-member plurality system. A party that does not have the support of a majority of Canadians can still win the majority of the seats in the House of Commons and form a government. This same feature is viewed by those who would like to reform the electoral system as evidence that the system distorts the electoral preferences of Canadians. (See Electoral Reform.) Smaller parties usually receive far fewer seats than their share of the vote would suggest they deserve. In fact, a party can win fewer votes than another party, but still win a majority of the seats. (See Election of 1896).

Regionalism

One of the effects of the single-member plurality system is to introduce a significant regional dimension to electoral results. (See Regionalism.) Political parties with concentrated regional support fare much better than parties with support spread across the country. This has made Canada’s electoral process particularly fertile ground for parties of regional protest.

This was seen most starkly in the 1993 election. It resulted in a serious challenge to the history of Canadian elections up to that point. The Liberal Party, which still held to traditional federalist policies, swept to a majority government. But two protest parties, the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and the Reform Party of Canada in the West, returned large numbers of MPs with strictly regional agendas. As a result, the Conservative coalition of Westerners and Québécois disintegrated. The Progressive Conservative Party was reduced to only two seats in the House of Commons. The Bloc promised to work for a sovereign Quebec and the Reform Party vowed a “renewed federalism,” which was seen by some as an attempt to exclude Quebec. That election was the first in a series between 1993 and 2011 in which four or five parties — including the Canadian Alliance, which formed from the remnants of the Reform Party — won seats in the House of Commons. Three minority governments resulted in that time.

The formation of the Conservative Party of Canada out of the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives in 2004, along with the collapse of support for the Bloc Québécois in 2011, ended this heavily regionalized period of Canadian politics. Given the structure of the electoral system, the places political parties win votes is almost as important as how many they win. Because of this, regional considerations will never completely disappear from Canadian elections.

Electoral Reform

Concerns over the exacerbation of regional conflict in Canada, along with other issues around representation, have led to calls for electoral reform in Canada. Some reform advocates call for a move to a more proportional electoral system; where the proportion of seats a party wins corresponds much more closely to the proportion of votes it receives. Others have advocated for systems that would use a preferential ballot. This would ensure that every candidate elected has the support of a majority of the voters in the riding.

]More often than not, a government is elected with a majority of seats but considerably less than a majority of votes. Since the Second World War, only two majority governments have received a majority of the vote — the Conservatives in 1958 and in 1984. (See also Elections of 1957 and 1958.) Another consequence of this political arithmetic is a regional concentration of political party representation. A party may appear strong in one region and weak in another. The disparity in the number of seats may be far greater than the actual distribution of the popular vote.

These debates at the national level have typically not gained much momentum. This is partly because the parties in power benefit from the current system and have less incentive to change it. The move to implement some form of electoral reform is politically divisive. Since reform stands to affect the number of seats each party wins in an election, the move to one system or another can arguably benefit one or more parties above others. Legal experts also point out that federal electoral reform may require a constitutional amendment — a historically difficult process. (See Constitutional History; Constitution of Canada.)

Provinces have been more adventurous in electoral reform, both in the past (Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia all used systems other than plurality voting at certain points), and in recent consideration of alternatives to the plurality system. There was significant discussion of reform at the provincial level in British Columbia, Ontario and Prince Edward Island in the 2000s (each of those provinces held a referendum on the matter); but no changes resulted.

Voter Turnout

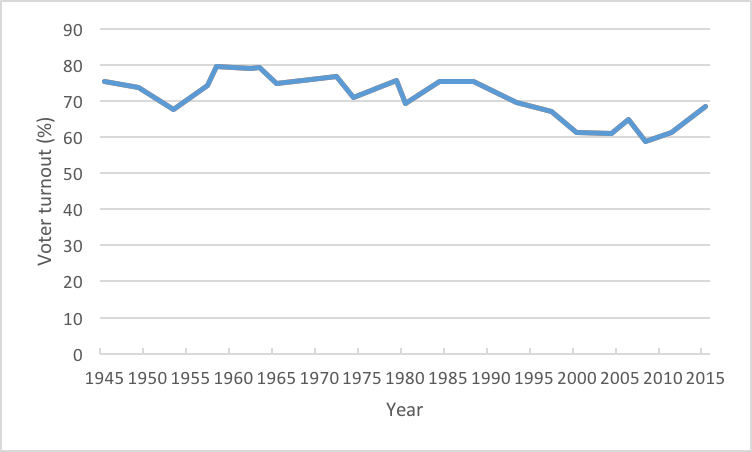

In recent federal elections, about 60 per cent of eligible voters cast a ballot. This represents a significant decline from the 75 per cent of voters who typically cast a ballot between 1945 and 1988. Similar trends can be seen at the provincial level. The same is true in other industrialized countries. (See also Political Participation in Canada.)

How often people take part in political activities depends on the type of activity and where they live in Canada. According to Canadian Election Study surveys, about 90 per cent of Canadians eligible to vote have done so at least once. Women, who gained the right to vote federally in 1918, vote at slightly higher rates than men. Older citizens are more politically active than younger ones. Turnout also tends to be lower among single parents and newer immigrants (who have obtained citizenship).

Prince Edward Island tends to have the highest turnout rates in the country, in both provincial and federal elections (74 per cent in the 2011 federal election). The lowest turnout of any province tends to be in Alberta (52 per cent in 2011). Turnout is often even lower in the territories (39 per cent in Nunavut in 2011).

This graph depicts a gradual decline in federal election turnout. In recent federal elections, about 60 per cent of eligible voters cast a ballot. This represents a significant decline from the 75 per cent of voters who typically cast a ballot between 1945 and 1988. Similar trends can be seen at the provincial level in Canada, as well as in other industrialized countries. Turnout in provincial elections has followed a similar trend to national elections. For example, in British Columbia, turnout was 77.7 per cent in 1983 and 51 per cent in 2009. In Quebec, it was 85.3 per cent in 1976 and 57.4 per cent in 2008. In Nova Scotia it was 78.2 per cent in 1978 and 58 per cent in 2009.

The causes of this decline in turnout were complex. One of the most important factors was a decline in voting among younger generations. Compared with their older counterparts — and compared with younger generations in years gone by — younger Canadians during this period were less interested in and less knowledgeable about politics; less engaged with formal political institutions; and less likely to see voting as a duty, rather than as a personal choice

However, in the 2010s, the voting rates in federal elections began trending upwards. After reaching a nadir of 58.8 per cent in the 2008 election, overall turnout was 61.1 per cent in 2011, 68.3 per cent in 2015 and 67 per cent in 2019. Somewhat surprisingly, the biggest gains in this period were among younger voters. According to Statistics Canada, voting among people age 18 to 24 increased from 55 per cent in 2011 to 68 per cent in 2019. Among people age 25 to 34, turnout increased from 59 per cent to 74 per cent.

Electoral Behaviour

Voters’ decisions about whom to vote for are shaped by a variety of factors, both long-term and short-term. Long-term factors include the social groups to which voters belong. These include religious, ethnic, class, regional and gender groups. Historically, for example, the Liberal Party benefited from the support of Catholic voters and visible minorities. These support bases have recently diminished. Similarly, voters are more likely to support political parties whose ideologies are like their own. Finally, some voters identify closely with a particular political party and are likely to vote out of traditional loyalties to that party.

Increasingly, however, short-term factors shape voter choice. The state of the economy can influence voters. Some are more likely to vote for a governing party when they perceive the economy to be growing and unemployment to be low or decreasing. During election campaigns, much of the attention is focused on the party leaders, and with good reason. Voters are more likely to vote for leaders they see as likable and competent. Some voters also vote strategically. To prevent a particular party’s candidate from winning, a voter might vote for their otherwise second choice. For example, an NDP supporter who disliked the Conservative Party might choose to vote for the Liberals if he or she thought that they had a better chance of defeating the Conservatives. (See also Electoral Behaviour in Canada.)

Electoral Fraud

Types of electoral fraud include ballot box stuffing; impersonation of voters; bribery and intimidation; and gerrymandering (the deliberate manipulation of constituency boundaries to give advantage to one party). Electoral fraud was once an acknowledged and largely tolerated aspect of Canadian elections. (See also Political Corruption; Conflict of Interest.) It has now been virtually eliminated and does not significantly impact the outcomes of elections. There is little tolerance in Canadian political culture for interference with the electoral process.

The Commissioner of Canada Elections investigated and pursued violations of the Canada Elections Act until 2014. This position was then moved from Elections Canada to the Public Prosecution Service of Canada. Most of these cases involve violation of political party finance laws; such as spending in excess of the spending limit, or making an illegal campaign contribution. Most of these are dealt with through “compliance agreements.” These are voluntary agreements between the Commissioner and the person violating the rules. In some cases, the Commissioner lays charges, which may result in jail time for offenders if they are found guilty. For example, in 2014, Conservative Party staff member Michael Sona was found guilty for his role in a scandal that saw some voters in Guelph, Ontario, provided with misleading information about the location of their polling stations. Such incidents, however serious, are relatively rare. They are punished aggressively by the Commissioner of Canada Elections.

See also Chief Electoral Officer; Political Participation in Canada; Political Campaigning in Canada; Political Party Financing in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom