Ensuring access to the United States market for exports, and attracting American capital and technology for economic development, have been overarching Canadian goals since Confederation. The relationship has always come with risks for Canada, including vulnerability to US interests. Managing it carefully is a constant of Canadian history.

Overview

Mouse and Elephant

Sustaining the Canada–US economic relationship ranks as one of Canada’s most important foreign policy objectives, since Canadian prosperity is closely linked to the health of the relationship and the growth of the United States economy. But given the great difference in the size and power of the two countries, the relationship can also generate tensions. US actions have great potential impact on Canada, but Canadian actions having little impact on the US.

Dependence on American capital and technology has also resulted in a high level of US corporate ownership and control in important sectors of the Canadian economy with important consequences. US corporate interests have been able to enlist the support of the US government in opposing policies that target development of Canadian industry. The US has also attempted to apply its laws to US subsidiaries operating in Canada to achieve its foreign policy goals.

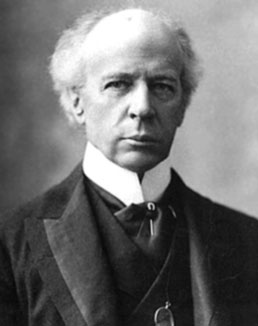

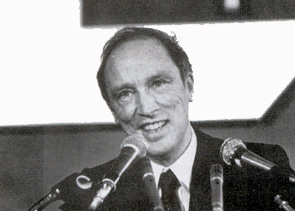

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau once remarked that living next to the US was like sleeping with an elephant — we are affected by “every twitch and grunt.” Prime Minister Lester Pearson observed that “to live alongside this great country is like living with your wife. At times it is difficult to live with her. At all times it is impossible to live without her."

Trade Flows

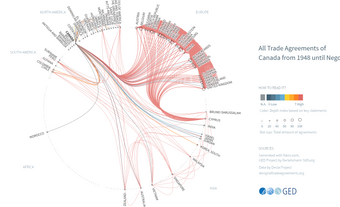

The Canada–US two-way merchandise trade is the largest bilateral trading relationship in the world, totalling $750.7 billion in 2014. Some 75.7 per cent of Canada's 2014 merchandise exports went to the US, equivalent to about 20 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Cross-border trade in services totalled another $119.3 billion.

Canada remains the largest export market for the US, accounting for about 19 per cent of US merchandise exports (about 67 per cent of Canadian imports) in 2014. Canada for the past 40-plus years has enjoyed a merchandise trade surplus with the US, with Canadian exports of natural resources offsetting imports of manufactured goods and technology. However, since 2007, China has displaced Canada as the largest exporter to the US while Mexico is also an increasingly important competitor in the US market.

Despite its merchandise trade surplus, Canada consistently records cross-border trade deficits in services and investment flows from direct and portfolio investment ($14 billion in services and $30 billion in investment income). The merchandise trade surplus in most years is sufficient to more than offset these deficits, giving Canada a current account surplus in its balance of payments with the US ($9.9 billion in 2014). The US is by far Canada's largest source of direct investment and debt capital, and by far the largest destination for Canadian investment abroad. (See Foreign Investment.)

Shared Infrastructure

Joint infrastructure has also furthered economic relations. In 1959, for example, the St. Lawrence Seaway was opened, providing ocean-going vessels access to Canadian and US ports on the Great Lakes. In 1961, the two countries signed the Columbia River Treaty, launching a major project to build and operate four dams for electric power and flood control, with three of the dams in British Columbia and one in the state of Montana. As the Canadian and US economies integrated in the second half of the 20th century, the two countries were closely linked through oil and gas pipelines, railways, highways, electricity grids and telecommunications networks.

Shared Concerns

Deepening economic ties over roughly 150 years reflect the ongoing evolution of the Canadian and US economies, from rural to industrial and now to knowledge-based economies. Globalization and technological change, shifts in demand for natural resources, as well as new concerns — for example, environmental challenges such as climate change, and geopolitical challenges such as terrorism and border security — have all shaped the ongoing relationship.

Post-Confederation

In the post-Confederation era, up to the end of the First World War, Great Britain was Canada’s dominant trading and investment partner. It was not until the start of the 1920s that trade with the US exceeded trade with Great Britain. Before the First World War, Canada–US trade was relatively small and concentrated, on the Canadian side, in agricultural products, fisheries and raw materials such as lumber, while imports from the US included manufactured products. In 1871, Canada’s population was just 3.7 million people, compared to 39.8 million Americans.

Early Free Trade Efforts

In 1866, as Canada’s Fathers of Confederation worked to launch the new Canadian nation, the United States abrogated the 1854 Elgin-Marcy Treaty with the Province of Canada (Québec and Ontario), which provided for free trade in agricultural products and natural resources, including timber, grain, meats, butter, cheese, flour, fish and coal. Although officially neutral, Britain had supported the Confederate states in the American Civil War — a key factor in US abrogation of the treaty. This was an unexpected blow and over the next 40 years Canada made repeated efforts to persuade the US to enter into a new reciprocal trade agreement, starting with Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s tariff act of 1868, which contained a standing offer of reciprocity.

Canada soon found itself battling a prolonged recession, with many Canadians moving to the US and some suggesting the country would be better off joining the US. Improved access to the American market was seen as essential. The government of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie in 1874 drafted a proposed reciprocity treaty that matched the 1854 agreement, but also added a long list of manufactured goods, including agricultural equipment, steel, locomotives, furniture, paper and boots and shoes. Known as the Brown-Thornton-Fish Convention, the proposal was rejected by the US, although it was approved by the British Parliament (acting for Canada).

National Policy

In office again after the 1878 federal election, Macdonald began implementing his proposed National Policy of high tariffs on manufactured imports (but lower tariffs on raw materials and intermediate products), as well as a coast-to-coast rail system and rapid settlement of the West. If Canada was to be denied the access it desired to the US market, it would create new opportunities within Canada for economic development through east–west nation-building.

This set the direction of Canadian development, including the evolution of a branch plant economy, into the middle years of the 20th century. Major US corporations first began establishing bases in Canada late in the 19th century, increasing US investment. For example, in 1892, Canadian General Electric was incorporated, and in 1898, Standard Oil of New Jersey acquired Canada’s largest oil company, Imperial Oil Ltd. It was estimated that US corporations owned 466 branch plants in Canada by 1918, and that 641 more were added over the next 12 years. Twenty per cent of the book value of Canadian industry was US-owned by 1930.

The Macdonald government felt it had little choice but to pursue a higher-tariff policy, facing a US policy of even higher tariffs. While US manufacturers were undercutting Canada’s nascent manufacturing industry by dumping excess goods into the Canadian market, there were also fears that unless Canada linked its various regions together and settled its sparsely populated western prairies, it would only be a matter of time before Canada was absorbed by the US. Yet the National Policy legislation also included a standing offer of a reciprocity agreement with the US.

Early 20th Century

Laurier, Borden and Reciprocity

In 1893, the Liberal Party pledged to pursue a reciprocity treaty with the US and went on to win the 1896 election. Little progress was made until 1910, when the American president, William Howard Taft, decided the time had come to develop a new bilateral relationship. The government of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier reported to the House of Commons in 1911 that a free trade agreement had been reached. By this time, Canada had a population of 7.2 million and a small manufacturing industry; the US, with 93.8 million people, was an emerging industrial power.

The US Congress approved the agreement in July 1911. However, the Laurier government, despite a parliamentary majority, decided to first hold a free trade election. The Conservatives under Robert Borden defeated the Liberals and the free trade agreement with the US was not implemented. Fears of annexation by the US and concern over the loss of the British connection, along with strong business opposition, doomed the agreement. Canada had spent nearly 45 years seeking a reciprocal trade agreement, but when the Americans finally agreed, Canada changed its mind.

Tariff Swings (1913–30)

In 1913, the US took a unilateral step in trade liberalization, passing the Underwood Tariff as part of the Revenue Act of 1913. The US initiative was designed to improve competition in the US market. It included a general reduction in tariff rates and the addition of many items to the free list, and it was highly favourable to Canadian exporters. Zero or near-zero tariffs were introduced for steel rails, timber, iron ore, agricultural equipment and a range of farm products. The value of Canadian merchandise exports to the US rose from $34 million in 1886 and $104 million in 1911 to $201 million in 1915 and $542 million in 1921.

But this promising period in Canada–US economic relations came to an abrupt end. Faced with an agricultural crisis, as farm prices collapsed, the US passed the Emergency Tariff Act of 1921, which sharply raised tariffs on agricultural imports. This was followed, in 1922, by the Fordney-McCumber Tariff, which completely reversed the trade liberalization in the Underwood Tariff initiative and dealt a harsh blow to Canada. Exports to the US fell to $293.6 million in 1922, from $542 million in 1921. Not surprisingly, Canada and other countries retaliated with higher tariffs of their own.

However, in 1922 and 1923, Canada invited the US to negotiate a reciprocal trade agreement. There was no US response. (Canadian exporters did benefit from US prohibition, which ran from January 1920 to December 1933, though smuggling profits did not show up in official statistics).

Great Depression

Worse was to come with the Great Depression. In 1930, the US enacted the Tariff Act of 1930 — the Smoot-Hawley Tariff — which took US tariffs to record levels, not only dealing an immediate and devastating blow to the Canadian economy but precipitating competitive rounds of protectionism worldwide, making the Great Depression much worse. In 1930, Canadian exports to the US totalled $515 million; by 1932 they had fallen to $235 million. Canada responded quickly, raising tariffs twice, in its 1930 and 1931 budgets. For example, tariffs on “luxury” cars from the US were raised to 40 per cent.

Canada also obtained preferential tariff arrangements with Britain, as well as Australia and New Zealand, at the 1932 Ottawa Economic Conference. This offset some of the damage from the harsh US measures but was not a long-term solution for Canadian economic growth and prosperity. By early 1933, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, who had once promised to “blast away” into world markets, had begun discussions with the US to improve market access.

A New Era

In 1933, the US elected a new president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Bennett met with Roosevelt in April, with the two leaders agreeing to increase trade. One of FDR’s early actions was to obtain the authority from Congress, through the 1934 Reciprocal Tariff Act, to lower or raise tariffs up to 50 per cent from existing levels in bilateral negations with other countries. A Canada–US agreement in 1936 was a modest step, but marked the beginning of an economic relationship that over time led to steadily declining tariffs and other trade barriers.

A second reduction in tariffs came with a subsequent 1938 agreement under the Reciprocal Tariff Act. These agreements made it easier to export commodities such as fish, lumber, cattle, dairy products and potatoes, as well as machinery and equipment to the US, while Canada reduced some of its barriers to imports. These were the first successfully concluded trade agreements between the two countries since the 1854 reciprocity agreement, a gap of roughly 80 years.

Mid-20th Century

Second World War

The Second World War led to closer economic ties and cemented the evolution of Canada into a North American economy. Canada needed access to US industrial supplies and dollars to undertake its war effort. In 1939, Canada passed the Foreign Exchange Control Act, limiting the use of its reserve of US dollars for essential wartime purposes. All Canadians were required to sell their holdings of foreign exchange to the Foreign Exchange Control Board and Canadians were not permitted to buy foreign exchange for pleasure travel.

Until the Second World War, Canada had regularly run trade deficits with the US but had offset these through its surpluses with Britain. Once war began, Canada no longer had the benefit of a trade surplus with Britain to help pay for imports from the US, which rose from $711 million in 1940 to $912 million in 1941. At the same time, to meet its industrial war and other needs, Canada found itself with a serious shortage of US dollars.

The growing urgency of the situation led to an April 1941 summit between Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and Roosevelt. Under the resulting Hyde Park agreement, Canada and the US agreed to co-ordinate production of war materials to reduce duplication and to enable each country to specialize. The US agreed to purchase certain war materials in Canada, which resulted in $200–$300 million in defence contracts over the following 12 months, helping Canada meet part of the cost of its imports from the US. By 1943, Canadian exports to the US had reached $1.1 billion (and $1.4 billion in imports), compared to $442.9 million in 1940.

At the end of the war, Canada again faced a severe shortage of US dollars — with exports of $887.9 million and imports of $1.4 billion — and once again turned to the US for help. The postwar economic recovery had led to a surge in imports as Canada experienced a sharp rise in domestic demand, along with conversion of its industrial base to peacetime production. In 1947, Canada again introduced exchange controls to limit the purchase by Canadians of US dollars to essential purposes. To assist Canada, the US allowed Marshall Plan recipients in Europe to use their US dollar credits to purchase Canadian goods and services, generating more than $1 billion in US dollars for Canada.

Oil Resources

The Second World War, and the subsequent the Cold War, led to increased US interest in Canadian natural resources, including oil and gas, for national security. The 1947 oil discoveries at Leduc, Alberta, and other discoveries in western Canada, meant that the US now had access to more secure oil supplies shipped overland rather than in ocean-going vessels. The US gave Canadian oil preferential treatment in what at the time was a highly protected market. There was a significant flow of US capital to develop Canada’s emerging oil and gas industry as well as its mining industry, including the takeover of many junior oil and gas and mining companies by US corporations. This also marked the beginning of a network of North American oil and gas pipelines.

The economic crisis in the mid-1940s and the growing interdependence in trade and resource development led to new discussions between Canada and the US for a free trade agreement. But Prime Minister Mackenzie King in 1948 halted discussions out of fear of rejection by Canadians concerned about the threat of assimilation into the US. Canada relied instead on successive rounds of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (now the World Trade Organization) to progressively improve access to the US market. These agreements over several decades led to the elimination or significant reduction in most tariffs between Canada and the US.

Defence Industry

Collaboration became more important in defence procurement during the Cold War. In 1959, Canada and the US signed the Defence Production Sharing Arrangement, following Canada’s cancellation of the Avro Arrow military aircraft. The two countries agreed to maintain trade in defence products in rough balance. Canada relied on the US for major military technology, while the US agreed to assist the development of a defence industry in Canada by eliminating tariffs on most Canadian military products and exempting Canada from Buy America provisions that required the US Defence Department to purchase US products. At the same time, US national security concerns had focused on Canadian resources following publication in 1952 of the President’s Materials Policy Commission, which warned of future shortages of domestically produced nickel, copper, iron ore, magnesium, zinc and lead, which could make the US dependent, in times of conflict, on insecure foreign sources.

American Ownership

US ownership and control of major Canadian industries had been a long-standing concern, but came to a head with the report of the Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects (the Gordon Commission) in 1957 and in various initiatives that followed. While acknowledging that Canada had benefited in terms of capital, technology and management skills from US investment, the commission, chaired by Walter Gordon, raised concerns about US domination in the oil and gas, mining and smelting, and various manufacturing industries.

Canada had relied on foreign capital for development since Confederation and without it, the economy would have been smaller and the standard of living lower. But in the 19th century, most of that capital came from Great Britain, mostly in the form of debt that was paid back and concentrated in railways, construction of utilities and funding of governments. In contrast, US investment from the late 19th century and in the 20th was in the form of direct investment, allowing permanent ownership and control of enterprises. By the 1920s, direct investment had become the most important form of foreign capital in Canadian industry, mainly in subsidiary companies or branch plants. In 1900, 85 per cent of foreign capital invested in Canada was owned in Great Britain and 14 per cent in the US. By 1955, the British share had fallen to 17 per cent while the US share was 77 per cent.

The concern of the Gordon commission was that US corporations controlled businesses in the fastest-growing sectors of the Canadian economy. “This concentration in key industries and in large companies wielding extensive influence is the most important factor to be considered in connection with foreign investment in Canada,” it said. It was also concerned that US subsidiaries would give preference to US suppliers of machinery and equipment, parts and components and professional services over competing Canadian suppliers, while good jobs in research and development, finance and corporate strategy would be held in US head offices.

The report proposed that wherever possible, branch plants should employ Canadians in senior management and technical positions, retain Canadian engineering and other professional and service personnel, and whenever possible do their purchasing of supplies, materials and equipment in Canada. The commission also called on foreign subsidiaries to publish full financial statements of their operations in Canada, include on their boards of directors a number of independent Canadians and sell an appreciable interest — 20–25 per cent — of their equity stock to Canadians. The commission also called for restrictions on foreign ownership in Canadian banks and life insurance companies.

Limiting US Ownership

In 1968, the report of the Task Force on the Structure of Canadian Industry was published, recommending the creation of a development corporation to support the growth of Canadian-controlled companies, and the regulation of foreign takeovers of Canadian companies. “The extent of foreign control of Canadian industry is unique among the industrialized nations of the world,” it said. In 1971, the federal government created the Canada Development Corporation to support the development of Canadian-controlled companies in the private sector, but it was dismantled in 1986. In 1972, Ottawa published another major report, Foreign Direct Investment in Canada, which led to the Foreign Investment Review Agency, which in turn required a review of all proposed new foreign investments in Canada or proposed takeovers of Canadian companies to determine where there was “significant benefit” to Canada.

In 1975, the federal government established Petro-Canada as a Crown Corporation to build a Canadian-owned presence in the oil industry (it was privatized in 1991 and merged with Suncor Energy in 2009). This was followed, in 1980, by the National Energy Program, which set the goal of 50 per cent Canadian ownership of the Canadian oil and gas industry by 1990. In 1979, 14 foreign, mainly US oil companies accounted for 82 per cent of Canadian oil production. A variety of measures were announced to favour Canadian-controlled oil companies, including Petro-Canada, initiatives strongly opposed by the US.

US Versus Canadian Law

At various times, tension has arisen when the US attempted to force Canadian subsidiaries to follow US policies and laws rather than Canadian laws and policies. In 1960, for example, Canada signed a three-year, $400-million contract to sell 200 million bushels of wheat to China, along with a follow-up contract to sell between 178 and 250 million bushels. The US strongly opposed the sale, and the Canadian subsidiary of a US company refused to sell the grain handling equipment to make the sale possible, citing US laws that made sales to China illegal. After negotiations between the two countries, the grain-handling equipment was supplied.

Following the Cuban revolution of 1959, the US imposed a trade embargo on Cuba and tried to force Canadian subsidiaries of US corporations to abide by the embargo. However, Canada insisted that the subsidiaries were subject to Canadian, not US laws. In 1984, Canada passed the Foreign Extraterritorial Measures Act, requiring companies in Canada to abide by Canadian laws rather than foreign laws. The law was amended in 1996, forbidding Canadian companies and Canadian subsidiaries of US corporations from complying with even harsher US restrictions on trade with Cuba that came into effect that year.

Auto Pact

In 1965, Canada took a transformative step in deepening cross-border economic integration with the signing of the Canada–US Automotive Products Agreement, or Auto Pact, whose purpose was to establish a single continental market for the industry. The agreement was negotiated to avert a serious trade conflict between the two countries, since the US had found Canadian auto industry policies to be in conflict with US trade laws. But the agreement was also seen as an efficient way to lower Canadian manufacturing costs through the gains from manufacturing fewer product models, but with longer production runs, for assemblers and parts manufacturers serving a single Canada–US market.

This was not a free trade agreement but a managed trade agreement. It did not include free trade for consumers but only for manufacturers, provided they met certain conditions (the agreement was limited to US-brand auto assemblers and Volvo, which had a small operation in Halifax). An auto maker had to maintain the same ratio of production to sales in Canada that had existed in the 1964 model year; increase Canadian value-added by $260 million by 1968; and from 1965 onward increase Canadian value-added by 60 per cent of the growth in the value of passenger cars sold — 50 per cent for trucks and 40 per cent for busses. For its part, Canada agreed not to pursue auto free trade with other countries.

The Auto Pact led to a surge of investment and production in Canada by the major US auto and auto parts companies and by 1970, for the first time, Canada had a trade surplus with the US in autos and auto parts. Canada’s share of Canada–US auto production rose from 7.1 per cent in 1965 to 12.6 per cent in 1970, and continued to rise, reaching 19 per cent in 1999 but falling to 17.7 per cent in 2013 and 17.4 per cent by the end of 2014.

The agreement soon became a source of friction: in the US view, the production and value-added conditions were meant to be temporary, whereas Canada insisted they were permanent. In 1971, the US came very close to abolishing the agreement. It had clearly worked to Canada’s advantage. In 1963, Canadian exports of automobiles to the US were valued at just US$813,000. By 1967, they totalled US$762 million and by 1977 US$3.7 billion. The pact was ended in 2001 after it was found to be contrary to World Trade Organization rules. But by then, the North American auto industry, with a strong Canadian presence, was already well established, with autos and auto parts the most important Canadian manufacturing exports to the US.

Canada's Vulnerability

As Canada’s economic integration with the US increased, so did its vulnerability to changes in US policy. This was clearly apparent in the 1960s as the US grappled with its own balance of payments problems, its long-standing global trade surpluses turning into deficits. Canada argued that its relationship with the US was special, and thus should be exempted from US balance of payments measures. But the US viewed Canada as part of the problem, saying Canada should borrow less in the US and do more to develop its own capital markets.

In 1963, the US introduced a tax on the interest and dividends earned by US citizens, and on foreign bonds, shares and commercial paper by corporations, in a bid to slow down the flow of US funds abroad. Given Canada’s high dependence on US capital markets, a crisis immediately emerged in Canadian financial markets, bringing significant pressure on the Canadian dollar and threatening a foreign exchange crisis.

Five days later, Canada obtained a conditional exemption: Canadian borrowing in the US could not increase above traditional levels and Canada was not allowed to increase its foreign exchange reserves through the proceeds of new US borrowing. In 1968, Canada agreed to additional conditions following the introduction of mandatory US controls on foreign investment by American multinational corporations, which were ordered to increase repatriation of earnings from their foreign subsidiaries, including those in Canada. This led to a further crisis for the Canadian dollar and Canada was forced to negotiate an exemption for subsidiaries of US non-financial corporations in Canada. (In 1974, the US lifted its interest equalization tax and other balance of payments measures.)

Faced with continuing balance of payments problems, however, the administration of US president Richard Nixon took drastic steps in 1971 with its New Economic Policy. It included a 10 per cent surcharge on all US imports, generous tax incentives for exports and a devaluation of the US dollar by ending the link between the dollar and gold, leading to the current system of floating exchange rates. At the same time, in bilateral negotiations, each major trading partner, including Canada, was pressured to take additional steps to help the US improve its balance of payments. Canada, for example, was threatened with cancellation of the Auto Pact.

A key lesson of the 1960s, culminating in the 1971 New Economic Policy, was the vulnerability of Canada to unilateral US actions. A 1972 government report, Canada–US Relations: Options for the Future, said Canada should reduce its vulnerability to US policies and pressures through trade diversification. “The object is essentially to create a sounder, less vulnerable economic base for competing in domestic and world markets and deliberately to broaden the spectrum of markets in which Canadians can and will compete,” the report said. It expressed fears that the US would become “an even tougher bargaining partner than in the past” as the US addressed its own economic problems. It quoted US president Richard Nixon who, in an earlier address to Parliament, had said that “no self-respecting nation can or should accept the proposition that it should always be economically dependent upon any other nation.” This was not the first time that Canada had looked to trade diversification, nor was it to be the last.

Energy Conflict

While Canada had long been viewed in the US as a secure source of oil and gas, access to the American market had not always been easy. In 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower established the Mandatory Oil Import Program, which imposed import quotas and licenses to stimulate domestic US production, which limited Canadian oil exports. But as US needs rose, the quotas were phased out.

With the sharp increase in world oil prices through the 1970s, Canada imposed an export tax on oil from 1974 until 1985 under the Petroleum Administration Act. The purpose was to sustain an oil price in Canada below the world price by using revenues from the tax to subsidize more costly oil imports used by refiners in eastern Canada. This was followed in 1980 by the National Energy Program, which included the goal of 50 per cent domestic ownership of the Canadian oil industry by 1990, assisted via a tax policy that favoured oil exploration by Canadian companies. The National Energy Program also sought to increase the Canadian share of engineering services, technology and machinery in oil and gas projects. Foreign multinationals in Canada, it was argued, tended to favour companies and technologies already used by their parent companies, thus depriving Canadian enterprises. The US vigorously protested these measures, and beginning in 1984 they were to a large extent unwound. The subsequent Canada–US free trade agreement (see "Free Trade Agreement" below) barred the future use of an oil export tax, and provided for equal treatment of Canadian and US companies in developing Canadian resources.

Late 20th Century

Mulroney Era

In 1984, the new government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney made restoring the Canada–US relationship a top priority. Much of the National Energy Program was unwound and the Foreign Investment Review Agency was replaced by Investment Canada, whose mandate was to promote investment in Canada and approve foreign investments that delivered a “net benefit” to Canada. Over time, the threshold for transactions subject to review has been increased, from $172 million in 1997 to $600 million in 2015. In 2013–14, the US was the leading source of investments, with 350 transactions valued at $18.18 billion, accounting for 52.6 per cent of all investments and 33.7 per cent by asset value.

By 2012, US-controlled subsidiaries accounted for 9.1 per cent of the total assets of Canadian industry, along with 15.8 per cent of total operating revenues and 20.6 per cent of operating profits. In manufacturing, for example, they accounted for 27.1 per cent of assets, 26.1 per cent of operating revenues and 27.9 per cent of operating profits. In the oil and gas sector they accounted for 19.5 per cent of total assets, 27.7 per cent of operating revenues and 13.8 per cent of operating profit. But in other sectors, such as finance and insurance and construction and utilities, US ownership and control accounted for a much smaller share of industry activity (in finance and insurance, for example, just 4.9 per cent of assets, 7.7 per cent of operating revenue and 6.7 per cent of operating profits).

Free Trade Agreement

In the early 1980s, following a severe recession, Canada again turned its eyes south in pursuit of ways to expand economic growth. This renewed interest in relations with the US was also prompted by growing fears of a resurgence of US protectionism. Based on the success of the Auto Pact, Canada and the US attempted to identify other sectors where they could pursue sectorial free trade. The exercise failed through lack of agreement on new sectors. As a consequence, Canada decided to seek a comprehensive free trade agreement and in 1985 the US agreed to begin negotiations.

President Ronald Reagan was open to the idea. In 1980, Reagan had called for a North American common market. A free trade agreement, it was hoped, would give Canadian businesses the economies of scale they needed to become more competitive manufacturers, would encourage the processing of Canada’s natural resources in Canada, enable Canada to attract investment from the rest of the world to serve the North American market, would bring an end to the threat of US protectionism and provide an exemption from US trade remedy actions. This, it was argued, would encourage innovation and boost productivity, and hence increase employment and raise Canadian living standards.

An agreement was reached at the end of 1987, coming into effect on 1 January 1989. While most Canada–US trade by then was already tariff-free or subject to only nuisance-level tariffs, the free trade agreement reached into many other policy areas, with Reagan declaring it an “economic constitution” for the two countries. In addition to eliminating tariffs on most products, aside from a number of agricultural products by both countries, it expanded free trade to cover a number of service sectors (culture was an exception for Canada), limited Canada’s ability to impose export taxes or other measures in the energy sector, introduced investors’ rights that allowed US corporations to sue governments in Canada if new policies deprived them of free trade benefits, liberalized foreign takeover rules so that a growing proportion of Canadian companies could be acquired by US companies without review by Investment Canada, and established a dispute settlement system.

A key Canadian objective — an exemption from US trade remedy laws —was not, however, achieved. Canada was still faced with punitive actions, such as subsequent US efforts to restrict softwood lumber imports, or US unilateral actions, such as Buy America restrictions in public infrastructure projects. Even before the heightened border rules that came after the terrorist attacks of 2001, exports from Canada required extensive paperwork to comply with rules of origin in the agreement which set minimum North American content thresholds. Moreover, while proponents argued that the free trade agreement would narrow the productivity gap between the two countries, instead the productivity gap widened.

The US subsequently launched free trade negotiations with Mexico, forcing Canada to negotiate inclusion in what became the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994.

Softwood Lumber

One of the most contentious and ongoing trade disputes — softwood lumber — predated the free trade agreement, was not resolved by it, subsequently became an important test of the agreement and has not gone away. The basic dispute arose in the early 1980s because Canadian softwood lumber producers were gaining market share in the US, with American producers seeking a protectionist solution. The two countries had different systems of pricing. Most Canadian lumber production takes place on Crown lands, with a stumpage fee being charged to collect a royalty, whereas in the US, much production comes from privately owned lands and a market-based auction system is used for pricing. In trade actions starting in 1982, US producers charged that the Canadian stumpage system gave Canadian lumber producers an unfair advantage, and that this constituted a subsidy. They said Canadian exports were unfairly causing injury to the US industry and that a penalty should be imposed on Canadian lumber imports.

Early efforts to persuade the US government to take action against Canada failed as US trade agencies failed to find injury or subsidy. But as a result of industry lobbying, a stiff 35 per cent tariff was imposed on Canadian shakes and shingles in 1986, with Canada retaliating with duties on books, computers, semiconductors and Christmas trees. The same year the US imposed a 15 per cent tariff on all Canadian softwood lumber imports. Later that year, Canada reluctantly agreed to introduce a 15 per cent export tax on softwood lumber exports and the US tariff was withdrawn.

This first softwood lumber agreement ran until 1991, when Canada decided not to renew it. The next year, the US re-imposed duties on Canadian lumber. In the meantime, various dispute panels reviewed the issue, with Canada in 1994 winning major victories. But the US was not deterred and, in 1996, the two countries reached a new agreement, which allowed duty-free shipments up to a quota ceiling, with a penalty imposed on all exports above the ceiling. The agreement expired in 2001.

The US remained determined to restrict lumber imports from Canada and in 2006 persuaded Ottawa to agree to a seven-year agreement, with provision for a two-year extension. This replaced US duties with a Canadian export tax, ranging from 5 to 15 per cent. Of the US$5 billion in duties collected by US authorities since May 2002, US$4 billion was refunded to Canadian companies while the US kept US$1 billion — despite a US court ruling that the duties had been collected illegally. The new agreement was implemented in 2006 and extended until October 2015.

Common Market?

While there have been periodic calls by business groups and think tanks to continue to deepen integration — for example, by means of a customs union or common market, adoption by Canada of the US dollar or a shared new currency — there has been no serious political take-up. The focus for governments has instead been on efforts to harmonize regulatory barriers. Other changes to bilateral trade rules are more likely to result from successful negotiation of the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership, which includes Canada, Mexico and the US, or a revived WTO.

21st Century

9/11 and Security

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 revealed once again Canadian vulnerability to changes in US policy. In the immediate aftermath, the US instituted lengthy border delays, with security trumping trade. Canada feared not only that American companies would switch to US suppliers, but also that border delays would be a powerful disincentive for companies to invest in Canada if part of planned production was intended for the US. It would be less attractive for US companies to source or locate production in Canada. Border delays also undermined just-in-time delivery systems and the notion that Canada and the US didn’t trade so much as make things together.

In effect, border delays threatened to undo the benefits of the free trade agreement unless new accommodations could be made. These included significant new investments by Canada in border security, and efforts to address US security concerns, starting with the December 2001 Canada–US Smart Border Declaration and Action Plan.

Trade and Regulatory Co-operation

In 2005, the three NAFTA countries launched the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America (SPP). Working groups were established to ease cross-border trade, including regulation of food health and safety and consumer product safety, as well as liberalized rules of origin. In 2006, the agenda was advanced, with an important role for the private sector through a North American Competitiveness Council. A North American Energy Council was also planned. But in 2009, the SPP was wound up after quite limited accomplishments.

With growing frustration from business and other groups over ongoing border issues, as well as concern for the future of North American economic growth, Canada and the US in 2011 launched the Beyond the Border Action Plan: A Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Economic Competitiveness. It highlighted areas of cooperation including trade, economic growth, jobs, infrastructure and cybersecurity. It included the creation of a Canada–US Regulatory Cooperation Council, linking agencies on both sides to deal with issues ranging from meat inspection and standards for natural gas vehicles to chemicals and toy safety in an effort to reduce regulatory differences as a barrier to trade.

Differences and Mutual Interests

Overall, the Canada–US economic relationship, despite great differences in size and power, has worked to the benefit of both countries. Yet while Canadians and Americans share many fundamental values, including the rule of law, there are important differences. In particular, Canadians tend to see government as a more positive force in the economy, hence the willingness to use public policy tools, including Crown corporations, to develop the economy and industry and to meet broader Canadian needs. The US Constitution, with its strict separation of powers, is based on a greater distrust of government. From the Canadian perspective, it is critical that the US understand legitimate Canadian interests and aspirations that differ from those in the US, just as it is important for Canadians to recognize US concerns.

While Canada’s dependence on the US is greater, both countries need each other. Just as changes in technology and regional or global forces have shaped the relationship in the past, new challenges — such as climate change and the rise of Asia as an economic power — will mean further changes in the future. Managing this relationship remains a fundamental challenge for Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom