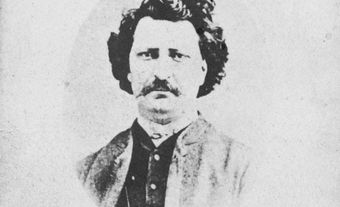

Gabriel Dumont, Métis leader (born December 1837 at Red River Settlement; died 19 May 1906 at Bellevue, SK). Dumont rose to political prominence in an age of declining buffalo herds. He fought for decades for the economic prosperity and political independence of his people. Dumont was a prominent hunt chief and warrior, but is best known for his role in the 1885 North-West Resistance as a key Métis military commander and ally of Louis Riel. Dumont remains a popular Métis folk hero, remembered for his selflessness and bravery during the conflict of 1885 and for his unrivaled skill as a Métis hunt chief.

Early Life

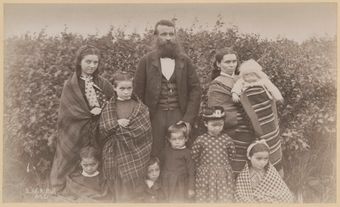

Gabriel Dumont was the eldest son of Métis hunter Isidore Dumont and grandson of French Canadian voyageur Jean-Baptiste Dumont. The Dumonts were a prominent Métis buffalo hunting family with a notable history of brigade leadership in the Saskatchewan country. They made their living as free hunters trading pemmican and hides with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Introduced to Métis buffalo hunting life in his early childhood, Gabriel Dumont mastered the many necessities of prairie life. Dumont could converse in seven languages, including Michif, Blackfoot, Sioux, Cree, Crow, and French, although he never learned more than a few words of English. He was an excellent marksman with both bow and rifle, a splendid horseman who possessed an extensive knowledge of prairie geography, and, like all Métis leaders, he had mastered the diplomatic culture of the northern plains.

In 1851, at the young age of 13, Dumont was introduced to plains warfare when he fought at the Battle of Grand Coteau, defending a Métis encampment against a large Dakota war party. In 1862, accompanied by his father, he concluded a treaty between the Métis and the Dakota. Later, he helped sign a treaty with the Blackfoot, which led to a lasting peace with the Métis’ traditional enemies.

Rise to Political Prominence

Dumont's skill as a buffalo hunter led to his election as hunt chief of the Saskatchewan Métis in 1863, a role he maintained until about 1881, by which time buffalo herds had virtually disappeared from the region. Dumont took no direct part in the Red River Resistance of 1869–1870, although he did rush to Fort Garry to offer military assistance to resist Colonel Garnet Wolseley’s expeditionary force. Some sources indicate that Riel’s Provisional Government declined the offer, hoping instead for a peaceful resolution. After the Resistance, during the 1870s and 1880s, he owned a farm and operated a ferry at Gabriel’s Crossing near a place on the South Saskatchewan River where many Métis families settled after being pushed out of Manitoba.

Dumont was a visionary leader who recognized that the decline of the buffalo alongside increased Canadian agricultural settlement would result in great change on the prairies. He undertook a long-term political program aimed at maintaining the political and economic independence of Saskatchewan Métis. On 10 December 1873, Dumont called a meeting to form a new government for the Métis settlement of St. Laurent on the South Saskatchewan River. He was immediately elected president of the new Council of St. Laurent. A Métis government based on the buffalo hunt, the Council institutionalized the Métis system of landholding on the South Saskatchewan River and devised a foundational legal code. With popular participation, Dumont instituted a formalized constitution that was written down for posterity by the local priest, Father André.

As president, Dumont oversaw a committee of elected councillors and assumed the role of mediator, working out disputes among the people of St. Laurent. However, with Canada’s claim to sole governing authority in the region, the Council of St. Laurent faced political interference from its inception. Dumont had made clear to Canadian officials that the community was simply forming a local government and not a secessionist movement, and many colonial officials saw little cause for alarm. When officials in London, England, were notified of the movement, the British Secretary for the Colonies wrote that “it would be difficult to take strong exception to the acts of a community which appears to have honestly endeavoured to maintain order by the best means in its power.”

At the same time, the Council did seek a degree of autonomous sovereignty, and had no intention of relinquishing the territory to the Canadian land surveyors who began arriving in the 1870s and refused to respect the Métis system of land tenure. Sir John A. Macdonald’s government, meanwhile, showed no signs that they intended to treat the Métis as a self-governing Indigenous people, and the arrival of The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) on the plains in 1874 significantly ratcheted tensions.

Dumont, Riel and the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan

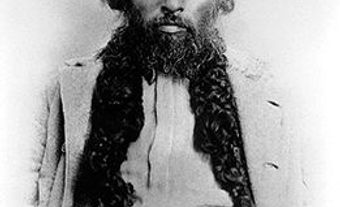

Dumont and his council sent several petitions to Ottawa in the early 1880s, insisting that Parliament recognize their land holdings and include river lots in the Dominion survey of the West. Having received no official response, the Métis at St. Laurent felt compelled to protect their land on their own terms. Dumont and several of his councillors decided in March 1884 to approach Louis Riel, whom the Métis considered an expert on dealing with Canada. A delegation was dispatched two months later to request that Riel travel to Saskatchewan to advise the people there on how to protect their lands and their freedoms. Dumont travelled with three others to St. Peter’s Jesuit Mission in the Montana Territory and convinced Riel to travel north to the Saskatchewan country. Riel and Dumont would develop a close friendship from that point on.

In March 1885, as Métis attempts to negotiate with the Dominion government had still gone unanswered, Dumont called a general meeting of the St. Laurent Métis at Batoche. Several of the Métis present suggested taking up arms to defend their lands against Canadian settlement. Dumont offered to lead the St. Laurent defence if the people were committed to it. When this meeting resolved to form a new provisional government — the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan — in order to negotiate with Canada and defend Métis lands, Dumont was chosen as the "adjutant-general," organizing about 300 Métis soldiers in the same manner as the buffalo hunt. While Riel was officially the president of the provisional government, Dumont remained a central leader in the community and responsible for many political and military decisions.

The North-West Resistance

Around this time, rumours that the Métis planned to attack Fort Carlton circulated, and the NWMP was dispatched to quash the Métis government. The Métis hastily organized a defence, and met with the NWMP near Duck Lake on 26 March 1885. After a botched parley where the NWMP shot and killed an unarmed Cree named Assiwyin and Gabriel Dumont’s brother Isidore, the Métis returned fire, killing three Mounties and nine volunteer militiamen. Many Métis maintained that this battle was fought in self-defence, as the Canadians opened fire, killing diplomats who were sent to avoid armed conflict. Dumont was shot in the head during the battle, the bullet glancing off his skull. He nursed this injury during the rest of the North-West Resistance, but it did not prevent him from leading his soldiers.

Aware that more Canadian troops, organized by General Frederick Middleton, were heading towards them, Dumont proposed a clandestine guerilla campaign that would target railroads and Canadian soldiers. The Provisional Government decided against the campaign. Riel preferred a peaceful resolution to hostilities, choosing to confront Canadian soldiers only when no other options were available. Although Dumont wished to engage the Canadians earlier on, he deferred to Riel’s judgments.

Dumont’s militia fought Canadian soldiers at Fish Creek on 24 April, initially stunning the inexperienced force and causing General Middleton to delay his advance toward the Métis stronghold of Batoche. At Batoche, Dumont led a spirited four-day defence of the community between 9 and 12 May 1885. Despite facing a superior force, he incapacitated a military river steamer and repelled several infantry pushes. On the fourth day, when Métis were out of ammunition and were shooting nails and scrap metal, the Canadians broke through their lines. Batoche was sacked, and Dumont was forced into hiding. Dumont remained in the Batoche area for days after it fell, distributing blankets to the displaced Métis women and children and making sure that they were safe from harm. He also searched for Riel, who had surrendered before Dumont could find him. Upon learning that Riel was in custody, Dumont left for the United States.

Later Life

Dumont was still a wanted man in Canada and had developed a popular mystique in the Saskatchewan territory. It was rumoured that he was mounting a daring rescue mission during Riel’s trial in Regina, which kept Riel’s guards on high alert. It was also said that when Dumont was in hiding, soldiers looking for him made little attempt to find him after learning that he was still armed with his famed rifle, Le petit. Upon arriving in the US, Dumont and his companion Michel Dumas were detained, but the local authorities shortly received a communiqué from the Oval Office ordering their release. Given the substantial acrimony surrounding Riel’s trial, the Canadian government never requested Dumont’s extradition. In July 1886, the Canadian government announced an amnesty for Dumont. He seems to have travelled through the US extensively in the years that followed, and visited Montréal in 1888 and Saskatchewan two years later. In 1893, he returned to Batoche permanently, where he dictated two vivid memoirs of the North-West Resistance. He died suddenly of heart failure on 19 May 1906.

Did You Know?

In 1903, Gabriel Dumont dictated his memoirs to a group of friends. The 103-page manuscript remained unseen and unpublished in the Manitoba Provincial Archives until discovered by Michael Barnholden in 1971. It was translated into English (from a mixture of French and Michif) and published by Barnholden as Gabriel Dumont Speaks in 2009. In his memoirs, Dumont told the story of how he and a small group of Métis leaders travelled to Montana in 1884 to ask Louis Riel to help them fight for their people’s land and political rights in Saskatchewan. According to Dumont, Riel answered “It has been fifteen years since I gave my heart to my country. I am ready to give it again now…” Dumont also recalled the horrible bullet wound he suffered at the Battle of Duck Lake in 1885, during the North-West Resistance: “There was a cut two inches long and three-quarters of an inch deep, right on the top of my head…I suffered through the whole war, from Fish Creek to Batoche, shouting in pain all day long. My head bled all night.”

Legacy

Gabriel Dumont’s legacy among Métis leaders is second in importance only to Louis Riel’s. His life serves as an example of selflessness, as he continued to protect vulnerable Métis families after Batoche had fallen, and fought a war to protect Métis lands from settlement knowing that his own land title would be recognized by the Dominion government. Dumont thus had everything to lose by fighting in 1885. In fact, his own home was burned and pillaged by Canadians, whereupon he lived with relatives for the rest of his life.

His life was remembered with much more fondness in the years following 1885 than the more divisive Louis Riel. Even in the immediate aftermath, when Dumont was in exile in the US, he enjoyed minor celebrity and was briefly employed in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, which promoted him as a rebel leader and a wanted man. Perhaps because of Dumont’s life as buffalo hunter, he captured the romantic imagination more than Riel, who remained a controversial figure until the 1960s. However, with the revival of interest in Métis history, politics and culture, both Riel and Dumont have become popular public figures for Métis and Canadians alike.

For many Métis, Dumont represents the best of Métis culture. He was a fighter and warrior but was ultimately driven by an overriding concern for his people’s welfare. Dumont is remembered in countless stories, poems, books and works of art. His namesake adorns many Métis institutions, most notably the premier Métis research centre, the Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research, which has published a book by Darren R. Préfontaine on the legacy of Dumont: Gabriel Dumont: Li Chef Michif in Images and in Words.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom