Canadian Expansion and Indigenous Lands

After Confederation in 1867, the Dominion government expanded westward in an effort to secure its political and economic future. In 1869, the government purchased Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company. This vast area stretched from Labrador to the Rocky Mountains and from the forty-ninth parallel to the Arctic Ocean. (See North-West Territories (1870–1905).) Canada intended to use natural resources and lands in the West to promote Western settlement and railway construction. These were key elements of the government’s development strategy. (See National Policy.)

However, the Indigenous inhabitants of the land were not consulted about its sale. As a result, the Métis of the Red River resisted and formed a provisional government to assert their authority. (See Red River Rebellion.) In 1870, the province of Manitoba was created to meet Métis demands. (See Manitoba Act.) The following year, treaty negotiations with First Nations peoples in the region began. Lieutenant-Governor Adams G. Archibald stated that whether Indigenous peoples “wished it or not, immigrants would come in and fill up the country… and that now was the time for them to come to an arrangement that would secure homes and annuities for themselves and their children.” (See also Treaties 1 and 2.) In the Numbered Treaties that followed, First Nations were required to cede their land to the Crown. In exchange, they received reserve lands, payments, and hunting and fishing rights.

Dominion Lands Act of 1872

The Dominion Lands Act of 1872 was modelled on homestead legislation that was passed in the United States in 1862. The Dominion Lands Act provided the legal authority under which the Crown granted lands to individuals, colonization companies, the Hudson’s Bay Company, railway construction, municipalities and religious groups. The Act also set aside land for First Nations reserves. An 1883 amendment to the Act set aside lands for National Parks.

The Act devised specific homestead policies to encourage settlement in the West, covering eligibility and settler responsibilities. At first, any man over the age of 21 was eligible to land patents for a “quarter-section” — a 65-hectare (ha) plot. However, eligibility changed over time. In 1873, the age was dropped to 18, making it easier for young families to homestead. Women over 18 who were the sole head of a family became eligible in 1876. In 1919, the widows of war veterans could also receive patents.

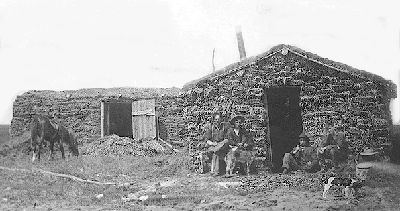

Policy varied over time, but most eligible homesteaders who paid a $10 administrative fee were given three years to build a habitable residence (see Sod Houses), clear the land for farming and cultivate a certain area annually. Homesteaders were expected to live on the lot for at least six months of each of the three years. Such requirements were created to discourage land speculation (when people purchase property, only to sell it later at a profit) and encourage long-term agricultural settlement in the West.

Once authorities decided that progress had been made on a quarter-section, the settler received ownership of the land. They also became eligible to purchase up to one full section (260 ha) to expand their farms. If improvements had not been made, the land could be taken back by the government and made available to other settlers. From 1870 to 1930, roughly 625,000 land patents were issued to homesteaders.

Métis Scrip

After 1885, the federal government offered Métis families what was called scrip in exchange for their land title. Scrip could be issued as land scrip, equivalent to a quarter-section of land (65 ha) or a 97-ha plot. It could also be issued as money scrip, valued at $160 or $240. Similar to the treaty system, Métis scrip was a means to remove Métis title to their lands and make way for White settlers.

Many Métis were entered into the scrip arrangement unscrupulously, with agents forging their signatures. Others were pressured into selling their scrip for less than face value to land speculators who would later sell the scrip to homesteaders at a profit. Most of the arrangements for scrip were carried out individually. But scrip was also offered to the Métis during the negotiations of Treaty 5, Treaty 8, Treaty 10 and Treaty 11. Many Métis were left homeless as a result of this system. Evidence suggests that the federal government was aware of the scrip system’s flaws. (See Métis Scrip in Canada.)

Dominion Land Survey

The Dominion Lands Act outlined a standard measure for surveying and subdividing land. Surveying was carried out by the Department of the Interior’s Dominion Land Survey. A simple, effective system divided the arable prairie lands into square townships. Each township comprised 36 sections of 260 ha, which were further broken down into 65 ha “quarter-sections.” These quarter-sections were offered as homesteads. This system of measure covered some 80 million ha, representing about 1.25 million homesteads — making it the largest survey grid in the world.

The Western settlement project was so expansive that the federal government created the Department of the Interior in 1873. It managed five branches: Dominion Lands, Indian Affairs, the Geological Survey of Canada, Ordnance and Admiralty Lands, and the North-West Territories.

The terms of Canada’s purchase of Rupert’s Land stipulated that the Hudson’s Bay Company was entitled to retain possession of 1/20 of the land. That meant the company received nearly two quarter-sections in each township. Two sections in each township were also reserved for the support of education. A variety of grazing, haying and mining leases were available for lands not yet claimed for homesteading.

Land Subsidies

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was seen as a national necessity and was financed through an elaborate system of land subsidies. It was not possible to sell most of the lands before the railway was built. So, when large sums were needed to pay for the construction costs, the federal government authorized the issuance of land grant bonds. It also provided substantial cash subsidies. Once the CPR was completed, the desire to open new areas to settlement and to bring in more settlers resulted in the granting of land to various colonization companies. These companies were expected to bring out settlers, construct needed branch lines and provide other assistance needed to establish new agricultural communities in the West.

Immigration and Settlement

In the three decades after 1870, settlement on the Prairies was slow. This was perhaps the result of a period of economic recession that lasted from 1873 to 1896. Immigration to Canada and the West was aggressively promoted during Clifford Sifton’s tenure as Minister of the Interior (1896 to 1905). During that time, the annual number of immigrants to Canada rose from 16,835 to 141,465. Hundreds of thousands of settlers made their way to the Prairies.

Sifton was adamant that immigrants and settlers be from farming backgrounds. He described the ideal settler as the “stalwart peasant in a sheep-skin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half dozen children.” (See also Immigration Policy.)

During this period, the government engaged in an aggressive advertising campaign for free homestead lands in “The Last Best West.” It also worked with international agencies to bring immigrants to the West. By 1914, roughly 170,000 Ukrainians, 115,000 Poles, and tens of thousands of German, French, Norwegian and Swedish immigrants settled in the West. Many of these immigrants settled in ethnic blocs, in which entire townships consisted almost entirely of one ethnic group. (See also Ukrainian Settlement in the Canadian Prairies.)

However, not all settlers were welcomed. Immigrants to Canada were selected based on preference, with British, Americans, Northern Europeans and Scandinavians topping the list. Italians, South Slavs, Greeks, Syrians, Jews, Asians, Roma people and Black persons were at the bottom of the list. (See also: Chinese Head Tax in Canada; Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 — the Proposed Ban on Black Immigration to Canada.)

Repeal of the Dominion Lands Act

Prairie politicians saw federal control over Western Dominion lands and natural resources as an unfair intrusion into areas that had been assigned to provincial jurisdiction in the British North America Act. (See also: Federal-Provincial Relations; Distribution of Powers.) Negotiations undertaken to transfer control of the remaining Western lands and resources to the provincial governments of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta were completed in 1930. (See Natural Resources Transfer Acts, 1930).

See also: Métis Settlements; Pioneer Life; Homesteading; History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies; Barr: An All-English Agrarian Settlement in the Prairies; Country Life Movement; History of Agriculture to the Second World War.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom