Conscription is the compulsory enlistment or “call up” of citizens for military service. It is sometimes known as “the draft.” The federal government enacted conscription in both the First World War and the Second World War. Both instances created sharp divisions between English Canadians, who tended to support the practice, and French Canadians, who generally did not. Canada does not currently have mandatory military service. The Canadian Armed Forces are voluntary services.

How Does Conscription Work?

Under conscription, all males of a certain age must register with the government for military service. In some countries, females are also conscripted. Once registered, these people may be “called up” for military service. Some people may be exempt (excused) from mandatory military service. This could include people in certain occupations or who suffer from physical or mental illness or disability.

Does Canada Have Conscription?

Canada does not currently have conscription. Some countries have mandatory military service (e.g., Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Norway, Turkey, Switzerland, Sweden, Israel). But it is unlikely that Canada will reintroduce the draft. During the First and Second World Wars, conscription created deep divisions in the country. This experience has contributed to deep unease about the practice among Canadians.

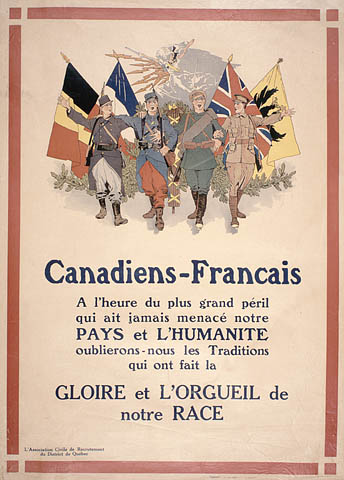

Conscription in the First World War

During the South African War (1899–1902), several thousand Canadians volunteered to fight for the British Empire overseas. Conscription for Canada’s limited war effort in South Africa had therefore not been necessary. The same was true during the early years of the First World War. From 1914 to 1915, some 330,000 Canadians willingly enlisted to fight against the Germans in France and Belgium.

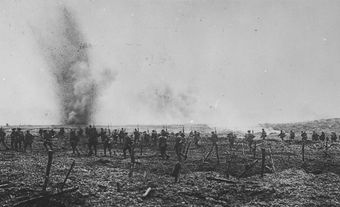

By late 1916, however, the relentless human toll of the war and the horrific number of casualties were beginning to cause reinforcement problems for the Canadian commanders overseas. (See Canadian Command During the Great War; Canadian Expeditionary Force.) Recruitment at home was slowing, and the manpower and enlistment system was disorganized.

For Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, the first necessity was to assist the men in the trenches. In May 1917, he returned to Canada from the Imperial War Conference in London and from visits to the trenches. He had decided that compulsory service was necessary and announced his decision in Parliament on 18 May.

Union Government

Borden was concerned that opponents of conscription, including the Liberal Party, would join forces to defeat the Conservative government in the general election that December. Borden decided that the best way to bring conscription about — while placating Quebec, where support for it was weak — was to bring his francophone opponent into a wartime coalition. On 25 May, he offered to form a coalition government with Liberal leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Borden promised the Liberals an equal number of seats in Cabinet in exchange for their support for conscription.

However, after consulting his supporters, Laurier rejected the proposal on 6 June. Laurier believed Quebec would never agree to conscription. He feared that if he joined the pro-conscription coalition, French Canada would be delivered to the hands of such Quebec nationalists as Henri Bourassa. (See also Francophone Nationalism in Quebec.)

After enormous difficulty, the Military Service Act became law on 29 August 1917. It made all male citizens aged 20 to 45 subject to call-up for military service, through the end of the war. Virtually every French-speaking member of Parliament opposed conscription; almost all the English-speaking MPs supported it. The eight English-speaking provinces also endorsed Borden’s move, while the province of Quebec opposed it.

In October, after months of political manoeuvring, Borden announced a Union Government; it was a coalition of loyal Conservatives, plus a handful of pro-conscription Liberals and independent members of Parliament.

Did you know?

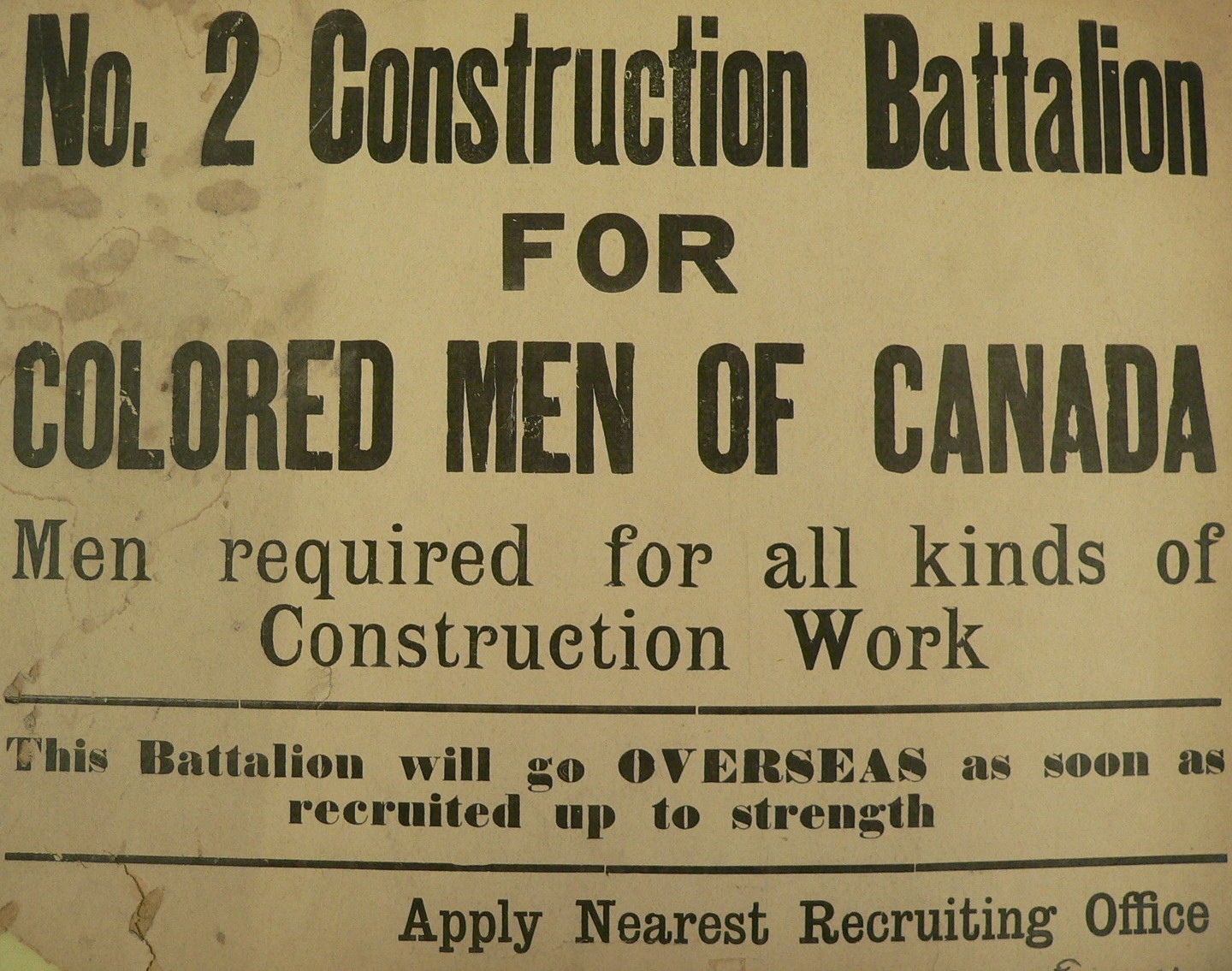

At first, the Military Service Act (MSA) included Status Indians and Métis men. However, some First Nations leaders challenged conscription on the grounds that it violated treaties between the Crown and Indigenous peoples. As a result, Indigenous peoples (both treaty and non-treaty peoples) were exempted from the MSA in January 1918. (See Indigenous Peoples and the First World War.) In contrast, Black Canadians were subject to conscription, despite the opposition that many Black volunteers faced when they tried to enlist earlier in the war. (See Black Canadians and Conscription in the First World War; Black Volunteers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.)

Wartime Elections Act

The controversial Wartime Elections Act became law on 20 September 1917. It extended the right to vote in federal elections to nursing sisters (women serving in the Canadian Army Medical Corps) and to close female relatives of military men. Canadian women had previously been denied the right to vote in federal elections. (See Women’s Suffrage in Canada.) By extending the vote, the Act was meant to entice voters who were likely to support the developing Union Government and conscription.

However, the Wartime Elections Act also removed the right to vote from thousands of people who were likely to vote against conscription. This included immigrants from “enemy countries” who had become citizens after 1902; although those citizens who had a son, grandson or brother on active duty in the Canadian military were exempted. The law also removed the right to vote from all conscientious objectors — those who refused to go to war because it was against their religious, moral or ethical beliefs. (See Pacifism.)

Election of 1917

The federal election of 1917 was divided. Neither French- nor English-speaking Canadians were unanimous in their views on the subject; but English Canada, broadly speaking, gave Borden his mandate to put conscription into effect. The Union Government won a majority with 153 seats, including only three from Quebec. Laurier’s Liberals won 82 seats, 62 from Quebec.

As a political measure, conscription was largely responsible for the re-election of the Borden government. However, conscription left the Conservative Party with a heavy liability — and feelings of betrayal — in Quebec and in the agricultural West (where the call up took people away from family farms).

1918 Anti-Conscription Riots

Anti-conscription riots broke out in Quebec. In 1918, the government used the War Measures Act to quell the anti-conscription Easter Riots in Quebec City between 28 March and 1 April 1918. Martial law was declared, and more than 6,000 soldiers were deployed. Rioters attacked the troops with gunfire and with improvised missiles, including ice and bricks. The Easter Riots grew increasingly violent and resulted in as many as 150 casualties. Four civilians were killed when soldiers returned fire on armed rioters.

How Many Men Were Conscripted in the First World War?

The process of call-ups began in January 1918. Certain exemptions from call-up were also lifted in the spring of 1918. Of the 401,882 men who registered for military service, 124,588 men were drafted to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Of those, 99,651 were taken on strength, while the rest were found unfit for service or discharged. In total, 47,509 conscripted men were sent overseas and 24,132 served in France. The rest served in Canada.

Conscription in the Second World War

Two decades later, as the threat of a new war in Europe became serious, the question of military conscription again caused lively political debate. However, in March 1939, both the Liberal Party and Conservative Party accepted a program rejecting conscription for possible overseas service. When Canada declared war in September 1939, the government renewed its pledge not to conscript soldiers for overseas service.

In June 1940, as Belgium and France fell to Nazi Germany, the public began to call for a more concerted Canadian war effort. In response, the government passed the National Resources Mobilization Act on 21 June. It provided for enlistment only for home defence. Registration took place almost without incident. A notable exception was the public opposition of Montreal mayor Camillien Houde. He was interned for four years after he urged constituents to ignore their call-up papers. (See also Internment in Canada.)

In 1941, as recruitment slowly progressed, more people spoke out in favour of conscription; first within the Conservative Party and later among English-speaking Canadians in general. To appease supporters of conscription, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King decided to hold a non-binding referendum asking Canadians to release the government from its anti-conscription promises.

In Quebec, the Ligue pour la défense du Canada was established to campaign for the “no” side. On 27 April 1942, 72.9 per cent of Quebec residents voted “no.” In all other provinces the “yes” vote triumphed by some 80 per cent. The government then passed Bill 80. It authorized conscription for overseas service if it was deemed necessary. Quebec’s Bloc populaire was formed in response to the Mobilization Act. The party continued to fight against conscription by presenting candidates for the August 1944 provincial elections and the June 1945 federal elections.

After D-Day operations and the Normandy campaign in 1944, J.L. Ralston, the minister of national defence, was convinced of the need for overseas conscription. Unexpectedly high casualties on the front, combined with a large commitment of manpower to the Royal Canadian Air Force and Royal Canadian Navy, left the Canadian Army short of recruits.

King, who had hoped he would not have to invoke Bill 80, replaced Ralston with General A.G.L. McNaughton, who did not support conscription. On 22 November, however, the prime minister acknowledged the pro-conscriptionist sentiments of many of his anglophone Cabinet ministers (who threatened to resign over the matter) and reversed his decision. He announced that conscripts would be sent overseas.

Did you know?

After conscription during the Second World War, the term zombie was used to describe the 60,000 men drafted under the National Resources Mobilization Act who had not volunteered for active service overseas. It was a derogatory term used to shame conscripted soldiers.

Only 12,908 conscripted soldiers, disparagingly known as zombies, were sent to fight abroad. This was a tiny number compared with the hundreds of thousands of Canadian volunteers, including French Canadians, who fought overseas. Only 2,463 reached the front lines before Germany surrendered in May 1945. Still, this second conscription crisis worsened relations between anglophones and francophones in Canada, though to a lesser extent than during the First World War.

See also Military Recruiting; Indigenous Peoples and the Second World War.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom