Carbon pricing refers to a cost that is imposed on the combustion of fossil fuels used by industry and consumers. Pricing can be set either directly through a carbon tax or indirectly through a cap-and-trade market system. A price on carbon is intended to capture the public costs of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and shift the burden for damage back to the original emitters, compelling them to reduce emissions. In 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a national climate change policy that includes a system of carbon pricing across Canada. Provinces can either create their own systems to meet federal requirements or have a federal carbon tax imposed on them. Nine provinces and territories have their own carbon pricing plans that meet federal requirements. Ottawa has imposed its own carbon tax in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario.

Coal-fired power plant (© Andreas Altenburger/Dreamstime)

Key Terms

Carbon tax: In the case of a carbon tax, a state directly charges money to companies that burn or distribute fossil fuels (typically per unit of carbon emissions). Companies may pass on the cost to consumers; as a result, a carbon tax can raise prices for gasoline and home heating fuel.

Cap-and-trade: A cap-and-trade system creates a market for carbon emissions. A state imposes a limit — or a “cap” — on total carbon emissions within its jurisdiction. The limit drops over time to meet an emissions goal. Companies then trade permits with each other in a regulated market system.

Background

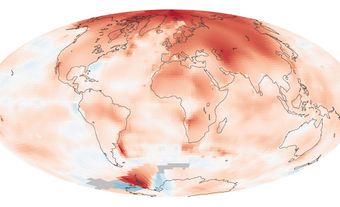

Climate scientists have warned governments for decades about the potential consequences of releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. (See Climate Change; Climate and Society.) In 1998, the government of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien signed the Kyoto Protocol, agreeing to reduce emissions to six per cent below 1990 levels by the end of 2012. The Kyoto Protocol allowed for “emissions trading” — commonly known as cap-and-trade — between countries to keep global emissions below a set limit. However, the Liberal governments of Chrétien and Paul Martin did not implement a carbon pricing system to meet those targets.

Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper opposed the Kyoto protocol when he came to power in 2006. His government formally withdrew from the accord in 2011. At that time, Canada’s emissions were 30 per cent above its Kyoto target. For the rest of the Harper period, Canada undertook few actions to reduce carbon emissions.

During the 2015 federal election campaign, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau promised to implement a Canada-wide carbon pricing plan; it would allow provinces to impose their own plans as long as they met federal standards. After he was elected, Trudeau and several provincial premiers attended the Paris climate summit in December 2015. The summit ended with an international agreement to limit the average global temperature increase to 2°C above preindustrial levels. To fulfill its side of the agreement, Canada promised to reduce GHG emissions by 30 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030.

Provincial Plans

Before the Trudeau government proposed its national carbon pricing plan, some Canadian provinces had already created their own carbon pricing programs.

In 2007, Alberta began charging $15 per tonne of carbon dioxide emissions beyond a set limit. In 2015, the province’s newly elected New Democratic Party (NDP) government under Premier Rachel Notley introduced a carbon tax plan; it increased the price on emissions to $20 per tonne in 2017 and $30 per tonne in 2018. In 2019, however, the United Conservative Party (UCP) government under Jason Kenney cancelled Alberta’s carbon tax.

Quebec, too, was an early adopter. It introduced a modest carbon tax starting in 2007 and a cap-and-trade program starting in 2013. Under that system, Quebec joined with California in a “carbon market” that allows companies to buy and sell emission permits issued by the province and the state.

British Columbia introduced Canada’s first broad-based carbon tax in 2008. It covers gasoline and home heating fuels as well as industrial activities. It was initially set at $10 per tonne of carbon dioxide emitted and rose to $40 per tonne by 2019. The tax was due to reach $50 per tonne by 2021, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the province only increased it to $45 per tonne on 1 April 2021. An increase to $50 was scheduled for 1 April 2022. The BC tax was originally “revenue-neutral.” This meant it was used to reduce other taxes. But the province now plans to use money from the tax to provide rebates to families and invest in climate change solutions.

Ontario joined the Quebec-California cap-and-trade market in 2018. However, Liberal premier Kathleen Wynne was replaced by Progressive Conservative premier Doug Ford later that year. Ford cancelled Ontario’s cap-and-trade program during his first week in office.

National Carbon Pricing Policy

At a first ministers conference in Vancouver in March 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the premiers reached an agreement on the need for a national strategy to meet Canada’s 2030 emission reduction target. In the Vancouver Declaration, issued on 3 March, the premiers committed to “transition to a low carbon economy by adopting a broad range of domestic measures, including carbon pricing mechanisms, adapted to each province’s and territory’s specific circumstances.…”

After months of debate and continued disagreement among the provinces, Trudeau announced the federal government’s new carbon pricing plan in October 2016. Ottawa would require all provinces and territories to have a carbon pricing system in place. For provinces using a carbon tax, the tax needed to be at least $10 per tonne at the start, then rise by $10 per year until it reached $50 per tonne in 2022. For provinces choosing a cap-and-trade approach, the emissions cap had to be lowered over time so Canada could meet its 2030 GHG target.

For provinces that did not meet the federal requirements, Ottawa would impose its own tax on the province. However, Trudeau promised that any money raised from a federal tax would go back to the provincial government to be used as they saw fit.

In April 2019, the federal government imposed a carbon tax on Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and New Brunswick. Prince Edward Island, Nunavut and Yukon opted to use the federal program in-part or whole. The rest of the provinces already had programs that met the federal requirements. New Brunswick later switched to an approved provincial carbon pricing plan. Alberta cancelled its carbon tax with the election of UCP leader Jason Kenney in 2019 and began paying a federal carbon tax of $20 per tonne on 1 January 2020; it was set to increase to $30 per tonne in April 2020 and to $50 per tonne by 2022.

Opposition to the Federal Plan

The federal plan was met with significant opposition, especially from Saskatchewan premier Brad Wall and Manitoba’s Brian Pallister. Saskatchewan took the federal government to court, claiming that Ottawa does not have the right under the Constitution to impose carbon pricing on the provinces. Two other challenges were launched by the Progressive Conservative government of Ontario and the UCP government in Alberta. The three separate appeals made their way through provincial courts to the Supreme Court of Canada. On 25 March 2021, the Court found that the federal carbon tax is constitutional, ruling against the provinces in a 6–3 decision.

In late 2020, the Trudeau government increased its GHG emissions target to 32–40 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. To hit this target, it proposed raising the federal carbon price by $15 per year after 2022, reaching $170 per tonne in 2030. The government also proposed a law that would bind Canada to a target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Impact of Carbon Pricing

Carbon pricing is somewhat of an economic experiment. (See also Economic Regulation.) The long-term economic impacts are not yet clear, nor is it perfectly understood how high a tax needs to be to reduce emissions. Critics of a carbon tax, such as members of Saskatchewan’s provincial government, argue that it is an unfair burden on consumers and makes provinces less competitive.

A World Bank review in 2016 found that a carbon tax had little impact on a jurisdiction’s economic competitiveness. A 2015 study of the carbon tax in British Columbia suggested that the tax successfully reduced emissions while having a “negligible” impact on economic activity. However, the tax had been frozen at $30 per tonne since 2012, and it did hurt some emissions-heavy industries such as cement production.

See also Taxation in Canada; Natural Gas in Canada; Oil and Natural Gas; Oil Sands.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom