Bombardier Inc. is a manufacturer of private airplanes that was once among the world’s largest manufacturers of trains and commercial airplanes. Headquartered in Montreal, the company was originally incorporated as L’Auto-Neige Bombardier Limitée in 1942. Its founder, Joseph-Armand Bombardier, was a Québécois mechanical engineer who invented one of the first commercially viable snowmobiles. Bombardier Inc. grew considerably from its beginnings as a snowmobile manufacturer into an iconic Canadian company, known for its public transportation vehicles and jetliners. Facing financial troubles in the 21st century, however, it began to sell off parts of its business. In 2020, it made deals to sell the last of its assets outside its private-jet business, including its commercial plane and rail divisions.

History of Bombardier Inc.

L’Auto-Neige Bombardier Limitée

In the 1920s, an American inventor patented the term snowmobile after he devised tracks and skis that fit onto Ford Model T and Model A cars, converting them into early snowmobiles. However, these snowmobiles were heavy and slow. During the 1920s and beginning at age 15, Joseph-Armand Bombardier also began developing a car-based snowmobile design. His desire to create vehicles that could move easily in the snow was shaped by the fact that he lived in the small town of Valcourt, Quebec, where winter snowfall was heavy and roads were not systemically cleared. This rural isolation turned tragic when, in 1934, Bombardier’s son Yvon died after his appendix burst and the family was unable to reach a hospital. The event further motivated Bombardier to develop a vehicle that could travel through snow.

By 1935, Bombardier had created a track system that turned with sprockets, or toothed wheels, which connected to and rotated the track. The sprocket, still on the Bombardier Recreational Products company logo today, enabled the creation of the seven passenger B7 auto-neiges in 1936. Along with the more efficient sprocket and track system, the B7 had a lightweight cabin, a new rear suspension system and improved weight distribution. The B7 found customers among clergy, postmen, army officers and travelling doctors. Bombardier set up a new factory in his hometown in 1941 and the following year incorporated L’Auto-Neige Bombardier Limitée. Many of Bombardier’s family members were major shareholders in the new company. Family shaped Bombardier’s operations for much of its history.

Bombardier Ltd.

In 1949, Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis began a rural road clearing program, reducing demand for snowmobiles. To contend with this slump in sales, the company created the Muskeg tractor, an all-terrain vehicle that could be used at isolated forestry, mining and oil work sites. Further, Joseph-Armand Bombardier continued to refine his snowmobile models in order to create a smaller recreational snowmobile (see Snowmobiling). He drew on advances in engine design, allowing for an engine small and powerful enough to drive a single or two-passenger vehicle he called the Ski-Doo. Launched in 1959, within four years Ski-Doo sales increased from 225 to 8,210, and the Valcourt factory expanded.

After this success, Bombardier died of stomach cancer in 1964. The firm’s presidency went to his son, Germain, who resigned within two years. Joseph-Armand’s son-in-law, Laurent Beaudoin, took over the company in 1966. Germain’s resignation was controversial. Beaudoin, who holds a Master of Commerce, contended that Germain lacked the managerial temperament or education required for the job, but rumours persisted that he pushed Germain out. Beaudoin remained the chief executive — almost uninterrupted — until 2008, and was instrumental in furthering the company’s diversification efforts. The firm changed its name to Bombardier Ltd. in 1967, reflecting Beaudoin’s ambition to expand the company beyond snow vehicles.

From Snowmobiles to Trains: 1960s and 70s

Marketing and engine refinements to the Ski-Doo contributed to the company’s revenue growth between 1964 and 1972, from $10 million to $183 million. During this period, the firm purchased the Austrian tram building firm Lohnerwerke GmbH, in 1970. Lohnerwerke’s subsidiary, Rotax, made motors for Ski-Doos. However, in 1973, sales abruptly declined due to a spike in oil prices (see Commodity Trading) and a series of winters with little snow. These challenges contributed to CEO Laurent Beaudoin’s desire to further diversify the company’s products.

In 1974, with encouragement from Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau and train building expertise from its Lohnerwerke subsidiary, Bombardier won the contract for 423 Montreal Metro cars for the city, to be built at the recently purchased facility in La Pocatière, Quebec. To further increase its manufacturing capacity, Bombardier took over the Montreal-based locomotive manufacturer Montreal Locomotive Works (MLW) in 1975. The Quebec provincial government facilitated the purchase by providing Bombardier with financial assistance. With this deal, the role of state money grew in significance for Bombardier’s operations, a trend that would persist through all of its expansions.

A strike by the Confédération des syndicats nationaux local in La Pocatière, lasting from 2 December 1975 to 20 April 1976, complicated the metro car contract. Workers protested limited wage increases during a period of major inflation, and expressed concerns about who the company was promoting on the shop floor. Delays led to Bombardier delivering only some of the cars in time for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal.

Meanwhile, poor management and labour trouble also beset the MLW plant in Montreal, including a lockout of 600 United Steelworker employees during the summer of 1977 and a six-month strike of 1,000 employees during 1979. Grand ambitions for the plant’s Light Rapid Comfortable (LRC) train cars, including a significant VIA Rail purchase, were dashed by persistent mechanical issues, and Bombardier shuttered the entire plant in the mid-1980s.

Orders from North American cities for public light rail and subway cars cushioned the losses from MLW. Following these successes, the company won a contract from the New York Metro Transit Authority for 825 subway cars in 1982. The order, valued at around $1 billion, was the largest single export sale by a Canadian manufacturer. It was facilitated by two things that were important parts of Bombardier’s operations: assistance from the Canadian government to help finance the deal, and use of another company’s expertise — in this case, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, a firm with personal transport, trains, shipbuilding, aerospace and other interests. The company also joined a trend of sending managers to Japan to learn about factory operations and managerial techniques.

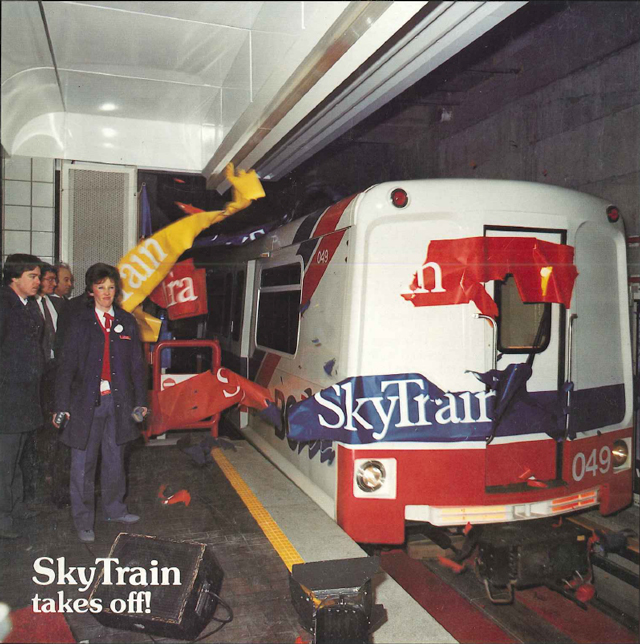

The success of the New York bid, which sparked orders from other North American cities, including cars for Vancouver’s SkyTrain, encouraged the company to expand its public transport capacity. The company identified Europe as a key market, given the importance of mass transit for most European countries. In 1986, Bombardier began to gradually absorb the Belgian railcar manufacturer BN Constructions Ferroviaires et Métalliques. The company continued to buy European rail firms, culminating in the $1.1-billion purchase of Germany-based Adtranz from DaimlerChrysler in 2001, making it one of the three largest train manufacturers in the world.

From Trains to Planes: 1980s and 90s

In 1986, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s government sought to privatize the federally owned aerospace firm Canadair. Bombardier initiated the purchase for four reasons: CEO Laurent Beaudoin’s constant interest in diversification, the relatively low purchase price (about $140 million), the prospect of owning and developing Canadair’s well-regarded Challenger jets, and the opportunity to use its new aeronautic expertise to secure contracts for maintaining Canada’s CF-18 fighter jets (see Military Aviation). When the Mulroney government awarded Bombardier the CF-18 contract over the bid of the Winnipeg-based subsidiary of Bristol Aerospace, long-held western suspicions of federal preference for eastern industrial development over western interests re-emerged. For years, the Reform Party and Canadian Alliance, both with considerable power in the West, would claim that Bombardier was a beneficiary of corporate welfare and federal favouritism for Quebec.

Following the Canadair purchase, Bombardier continued looking for value in struggling aerospace companies. In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government sought to privatize the Northern Ireland aerospace company Shorts in 1989, and Bombardier moved quickly to bid, offering $60 million. The company sought to acquire some of Shorts’ regional jet expertise (i.e., small, short-haul aircraft) and was encouraged by British government assurances that they would help fund the modernization of the plant, among other benefits.

Along with entering the commercial and military aerospace markets, Bombardier expanded into the private jet market with its 1990 purchase of Kansas-based Learjet for $75 million. Keeping with its tendency to accumulate other companies’ expertise, Bombardier kept much of Learjet intact, making only moderate adjustments to the firm’s managerial practices.

In 1992, Bombardier acquired aircraft manufacturer de Havilland Canada from another aircraft company, Boeing. De Havilland was particularly known for its Dash 8 commuter airplanes, complementing Bombardier’s regional jet production. Government contributions, including a 49 per cent equity stake in the firm purchased by the Ontario government, further facilitated the deal. By 1997, Bombardier transformed these government-supported purchases into about a 50 per cent share of the global regional jet market.

Restructuring

Following Bombardier’s significant expansion, CEO Laurent Beaudoin strained to manage the massive company. Under the direction of his executive vice president, Dr. Yvan Allaire, the firm restructured the management of its five operating groups in 1996 — aerospace, rail transportation, recreational products, international markets and financial services — each one getting its own president and chief operating officer. The relatively small Montreal headquarters, with about 150 employees, oversaw the five groups, but each unit was given considerable independence for making operational decisions.

Challenges in the 21st Century

Originally, the financial services arm of the company, Bombardier Capital, primarily concerned itself with arranging financing for snowmobile dealers. Inspired by how General Electric’s financial services unit, GE Capital, had expanded into financing a wide range of activities, Vice President Yvan Allaire led Bombardier Capital’s expansion into ventures unrelated to its core transportation businesses. These ventures included offering mortgages for high-risk, prefabricated home development, concentrated in Texas and South Carolina. However, this expansion failed, as many people who took on these mortgages were unable to pay their loans and investors found Bombardier’s mortgage business increasingly unappealing. Following this episode, by 2001 Bombardier had largely withdrawn from the mortgage market, having lost $663 million in company value.

Following the 2001 purchase of German train manufacturer Adtranz, Bombardier Transportation discovered they had underestimated the company’s costs and overestimated its assets, leading to a dispute between Bombardier and Adtranz’s parent company, DaimlerChrysler. During the purchase negotiations, DaimlerChrysler had refused to allow Bombardier to directly contact Adtranz’s management, since the two firms were still in direct competition, but Bombardier went through with the purchase anyway. In 2004, the two firms agreed to shave about $300 million from Bombardier’s original $1.1-billion purchase.

At the same time, Bombardier Aerospace struggled with stiff competition from the Brazilian company Embraer, and from a decline in the overall market following the 11 September 2001 attacks by the terrorist group al Qaeda in the United States (see 9/11 and Canada).

The company found itself in considerable trouble after two decades of rapid growth. Paul Tellier, the former Clerk of the Privy Council Office and CEO of Canadian National Railway, became CEO of Bombardier in January 2003. He undertook an aggressive program of downsizing, eliminating 3,000 aerospace jobs in Canada and Northern Ireland, 6,500 rail jobs in Europe, and closing down Bombardier Capital.

Seeking to improve the company cash flow, Tellier also decided to sell off the products that started the company. After considerable debate, he sold the recreational vehicle division in 2003, including the iconic Ski-Doo snowmobiles and popular Sea-Doo watercrafts. The Bombardier/Beaudoin family decided to purchase a 35 per cent stake in the new Bombardier Recreational Products company, which sold for nearly $1 billion. The firm is based in Valcourt.

Having made those controversial decisions, Paul Tellier left the CEO post in December 2004, and Laurent Beaudoin retook the position, eventually passing it to his son Pierre in 2008. In 2015, leadership transferred again, this time to Alain Bellemare — former executive at American aerospace and defence company UTC Propulsion and Aerospace, and only the second non-family member to run Bombardier. Under Bellemare’s direction, the company embarked on a five-year turnaround plan that saw it sell off significant parts of its business to reduce debt.

Final Rail Contracts

For several years, Bombardier continued to service national railways, including a major sale of 660 cars to a British rail operator in August 2016. It also remained involved in regional and municipal public transportation, including significant contracts with Ontario’s Metrolinx and the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). The Metrolinx and TTC contracts — for light rail vehicles and streetcars throughout the Greater Toronto Area — tested Bombardier’s reputation, as it missed several delivery deadlines. In 2016, the company’s woes were also reflected in a series of layoff announcements, beginning with 7,000 job cuts announced in February followed by another 7,500 announced in October.

In November 2018, a consortium of Bombardier and French train manufacturer Alstom received a $447.7-million contract to build 153 train cars for the Montreal Metro. The deal was crucial to the survival of Bombardier’s plant in La Pocatière, Quebec, where nearly 170 of its employees built the AZUR-model cars.

In February 2020, Bombardier reached a multi-billion-dollar deal to sell its rail division to Alstom. The announcement came within a week of Bombardier’s agreement to sell off its last stake in commercial aviation. With these decisions, CEO Alain Bellemare aimed to pay down debt and focus the company’s activities on the manufacture of private jets.

Aerospace Challenges and Downsizing

Under Bellemare’s direction, Bombardier’s aerospace business has also faced challenges and been downsized to pay off debt. Its C Series line of passenger aircraft, hailed for being larger and more efficient than other aircraft on the market, was plagued by cost overruns and delivery delays. In an effort to support the ailing project, the Quebec government gave Bombardier $1 billion in financing in 2015. While the company originally planned to deliver customers 15 aircraft in 2016, only one plane had been delivered by June. By September, the company announced it would only meet about half its 2016 delivery goals.

In September 2017, the C Series jetliner became the subject of international trade disputes. The United States levied a 219 per cent duty on C Series imports after American company Boeing complained to the US Department of Commerce that Bombardier had sold the planes to Delta Air Lines at an unfair advantage because Bombardier received government subsidies for the C Series. Meanwhile, the World Trade Organization announced it would establish a panel to investigate allegations by Brazilian company Embraer that Bombardier’s C Series program received unfair advantage from its government subsidies.

In October 2017, Airbus, a multinational aerospace corporation, bought a majority stake in the C Series program. In the deal, an Airbus plant in Mobile, Alabama, was repurposed for C Series assembly, which circumvented the large duty levied in September. Program headquarters remained in Montreal and Airbus was given the opportunity to buy the remaining stake in the program from Bombardier and the Quebec government. Airbus renamed the jetliner A220.

Bombardier continued to sell parts of its aerospace business. In November 2018, it announced the sale of its Q Series turboprop passenger aircraft program to Viking Air of Sidney, British Columbia. The US$300-million deal also gave Viking Air the rights to the de Havilland name and trademark, which Bombardier had owned since 1992. At the same time, Bombardier announced the sale of its business aircraft training activities to Montreal-based flight training company CAE for US$645 million. On top of these changes, Bombardier revealed it would lay off 5,000 employees: 2,500 in Quebec, 500 in Ontario and 2,000 outside Canada. The job cuts amounted to more than 7 per cent of the company’s workforce.

In June 2019, Japan-based Mitsubishi bought Bombardier’s CRJ regional jet business. In February 2020, Bombardier sold its remaining stake in the A220 program to Airbus and the Quebec Government. With these deals, the company shed the last parts of its commercial plane-making business after three decades in the market. Bellemare declared his turnaround plan complete and said Bombardier would concentrate on growing its private jet business.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom