The Métis community of Batoche is a national historic site in central Saskatchewan. It was the scene, in 1885, of the last significant battle of the North-West Resistance, where Métis and Indigenous resistors led by Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont were defeated by federal government militia, effectively bringing an end to the uprising.

Resistance

In the 1880s, with the decline of the fur trade and the destruction of the great bison herds, there was widespread disaffection among the various peoples who lived on the prairies of what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta. The Cree, Blackfoot and other Indigenous people faced starvation and the end of their way of life. The Métis were worried about title to their farms, and still felt vulnerable following their failed Red River Resistance in Manitoba a decade earlier. The federal government in Ottawa appeared unsympathetic to their concerns and their plight.

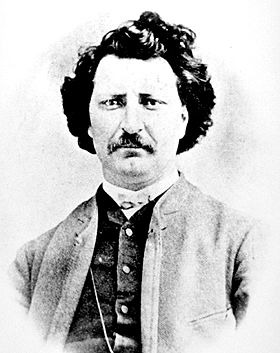

In March 1885, Métis leader Louis Riel – recently returned from exile in the United States – issued Ottawa with a series of demands for Métis land rights, set up a provisional government with himself as president, and seized the parish church in the community of Batoche with an armed force of Métis followers.

The government of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald responded by mobilizing militia troops (mostly in eastern Canada) and dispatching them quickly to the West on the newly built Canadian Pacific Railway line. By April, Maj-Gen. Frederick Middleton was in command of more than 5,000 federal troops in Saskatchewan.

A series of violent confrontations ensued between the militia, and the Métis and Indigenous resistance forces, through the spring of 1885 – culminating in a final engagement at Batoche.

Battle of Batoche

On 9 May, about 900 militia troops and artillery batteries under Middleton's command, attacked a force of less than 300 Métis, Cree and Dakota fighters dug into defensive positions south of Batoche. Middleton split his forces in two. The first group approached the enemy by river, from the Hudson's Bay Company steamer Northcote. The river attack failed when the Métis lowered a ferry cable, decapitating the Northcote's smokestack and leaving the steamer to float harmlessly downstream.

For two days, the Métis also effectively resisted Middleton's land forces – turning away repeated federal attacks by firing from elaborate rifle pits built under the supervision of the resistors' military tactician Gabriel Dumont.

Finally, on the morning of 12 May, two of Middleton's colonels, impatient with the impasse, led a frontal attack on the weakened defenders, who had run out of ammunition and were reduced to firing nails and stones from their rifles. The village of Batoche was captured by the federal forces, and the spirit of the resistance broken. More than 25 men from both sides were killed in the battle.

Louis Riel surrendered a few days later (he was eventually tried and hanged), Gabriel Dumont fled to the United States, and other participants were captured and held for trial.

Today

Batoche is now a national historic site, although the church and rectory are the only buildings standing from 1885. Remains of the Métis rifle pits and Middleton's camp can be seen, and Dumont and other Métis leaders are buried in the cemetery nearby. There is now a visitor reception centre to interpret the events of the battle, as well as explain the Métis' social and economic life.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom