The Asbestos Strike began on 14 February 1949 and paralyzed major asbestos mines in Quebec for almost five months. The Quebec government sided with the main employer, an American-owned company, against the 5,000 unionized mine workers. From the start, the strike created conflicts between the provincial government and the Roman Catholic Church, which usually sided with the government (see Catholicism in Canada). One of the longest and most violent labour conflicts in Quebec history, it helped lay the groundwork for the Quiet Revolution.

This is the full-length entry about the Asbestos Stike of 1914. For a plain-language summary, please see Asbestos Stike of 1949 (Plain-Language Summary).

Key Terms

Labour: Generally, labour means work. But in this article, it stands for workers (especially manual labourers) as a class or political power.

Labour union: A group of workers that forms to protect its members’ rights and to seek better pay, benefits and conditions. The term is often shortened to union. (See Labour Organization.)

Background

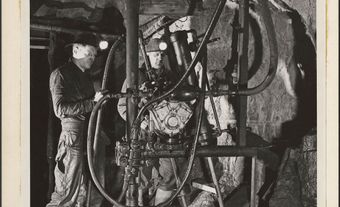

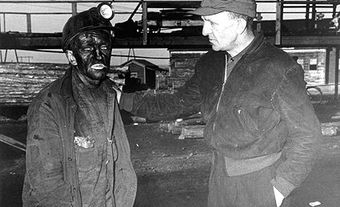

In 1949, Quebec supplied 85 per cent of the world’s asbestos. The mining town of Asbestos (renamed Val-des-Sources in 2020), in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, was the world’s major producer of the mineral. Its miners were seeking better wages and working conditions from the main employer, the American-owned Johns-Manville Company.

The inhalation of asbestos fibers was linked to the development of lung disease as early as the 19th century. However, asbestos remained in common use for insulation, soundproofing and fireproofing in buildings. It was also used in products ranging from furnaces to brake pads. Breathing in asbestos fibres can cause diseases such as asbestosis, mesothelioma and other cancers.

Miners Strike

On 14 February 1949, about 5,000 workers walked off the job at four asbestos mines in Asbestos and Thetford Mines, Quebec. They rejected offers of arbitration because they felt labour arbitrators usually sided with companies. Among their demands were a $1 per hour wage, nine paid holidays, union participation in the management of the mines, a pension, and action to limit illness-causing asbestos dust.

The traditionally conservative Canadian Catholic Confederation of Labour represented the miners. This was an umbrella group of many unions established by the Catholic Church to counter anti-clerical and socialist influence on Quebec workers from international unions. (See Confederation of National Trade Unions.)

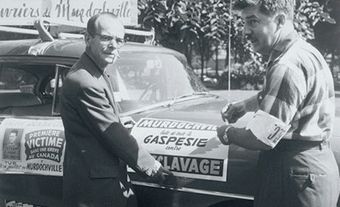

Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis backed the employers against the striking workers. Duplessis, who was known as “le Chef,” was premier of the province from 1936 to 1939 and again from 1944 to 1959. The leader of the conservative Union Nationale party, Duplessis ruled the province with an iron fist. The era eventually came to be known as La Grande Noirceur (The Great Darkness). Duplessis rewarded supporters with patronage and punished opponents with repression. He also used intimidation tactics to undermine unions that he felt would jeopardize American investment in the province. Days after the strike began, his government declared it illegal and sent provincial police to Asbestos.

Support from the Catholic Church

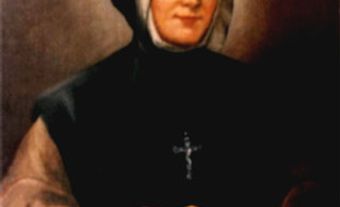

The Roman Catholic Church in Quebec backed the strikers. For the first time, it sided with labour in an industrial dispute. This put the bishop’s office in direct conflict with Duplessis.

In a sermon delivered at Notre-Dame Basilica, the archbishop of Montreal, Joseph Charbonneau, told parishioners: “The working class is the victim of a conspiracy aimed at crushing them, and when there is a conspiracy to crush the working class, it’s the Church’s duty to intervene. We value people more than capital.”

Charbonneau also requested that priests read from the pulpit an appeal to aid the strikers’ families. He asked them to fundraise by taking a collection at churches each Sunday during the strike. In response to his support for the strike, Duplessis seems to have successfully encouraged the Catholic Church to order the resignation of Archbishop Charbonneau, as well as his transfer to British Columbia. Charbonneau ended up as chaplain with the Sisters of St. Ann, an order of nuns in Victoria. Duplessis also called the Catholic union leaders “saboteurs” and “subversive agents” and ordered the arrest of 20 strike leaders on conspiracy charges.

Violence Erupts

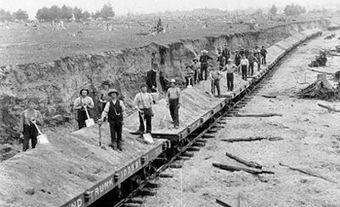

Shortly after the strike began, Johns-Manville Company hired replacement workers, who were supported by the police. To prevent the replacement workers from reaching the mines, the strikers set up roadblocks. On 14 March 1949, someone set off an explosion on a rail line to the plant. A few days later, workers beat a company official. The union set up a picket line, which stopped replacement workers and company officials from entering the plant. Johns-Manville took out a court order to end the picketing. Police enforced the order. Strikers threw rocks at the replacement workers. For their part, police at the picket line attacked the strikers with tear gas and fired warning shots into the air.

On 5 May, strikers beat and disarmed a dozen plainclothes police who were at roadblocks thrown up to block replacement workers. The following day, police clamped down, sending 400 officers into Asbestos. They arrested about 180 striking miners attending a union strategy meeting. Armed with guns, tear gas and billy clubs, the police beat several strikers. The arrests and beatings attracted worldwide media attention.

Did you know?

Pierre Elliott Trudeau, then a 29-year-old lawyer, was part of a large group of union activists who came from Montreal to support the union. He described finding at Asbestos “a Quebec I did not know, that of workers exploited by management, denounced by government, clubbed by police, and yet burning with a fervent militancy.” He later described the strike as a “turning point in the entire religious, political, social and economic history of the province of Quebec.”

Effects of the Asbestos Strike

The strike ended on 1 July 1949, with the two sides having negotiated a settlement. At the time, it was the longest labour dispute in Quebec history.

Workers made few gains from the strike. Miners received a wage increase of 5 cents an hour instead of the 15-cent raise they sought. The issue of asbestos dust exposure was not addressed. However, Johns-Manville Company raised miners’ wages within a year, making Quebec miners competitively paid in Canada.

Some paid a steep price. Many of the miners were not rehired. Joseph Charbonneau spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity in Victoria.

Along with Pierre Trudeau, Jean Marchand, who served as the strikers’ spokesman, and journalist Gérard Pelletier, who covered the strike for the Montreal newspaper Le Devoir, went on to have high-profile careers in federal politics in the 1960s and 1970s. They became known as the “Three Wise Men.”

The Asbestos Strike of 1949 represented the first crack in the power of Premier Duplessis. The miners’ fierce resistance, the public and media’s support for the strikers, and the rift between church and state signalled a major political and cultural shift in Quebec. It marked the beginning of a new era of Quebec nationalism that set the stage for the Quiet Revolution.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom