Architectural History: 1914-1967

On 3 February 1916 fire broke out on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. The following morning all that remained of the Centre Block (1859) was the famous pinnacled library and a few walls of rubble. Canada was at war with Germany, its citizens in uniform, but replacement began almost immediately. In their design the appointed architects, John A. Pearson and J. Omer Marchand, opted for continuity with the past.

When it opened in 1927 the proud neo-gothic form and commanding Peace Tower of the Centre Block made it a symbol of the now prosperous nation around it, a memorial to the thousands of Canadians who had died in Flanders fields. Built of steel and concrete, commodious and carefully planned, the new building was contemporary in structure and function. But even the most casual observer could see its massing and skin were an updated paraphrase of the building it replaced. Inside many of the public spaces were neo-Gothic in style.

This approach - traditional on the outside, modern underneath - was the dominant mode of fashionable Canadian architecture during the 1920s. In Ottawa it went hand in hand with the desire to create a unified architectural ensemble the length of Wellington Street. Remarkably successful, this interwar initiative included, besides the new Centre Block, the copper-roofed towers of the Confederation (1928-31) and Justice (1934-6) buildings (both Department of Public Works) as well as the Supreme Court (Ernest Cormier, 1938-9) and the Bank of Canada (Marani, Lawson and Morris, 1937-38).

Outside the capital, refined and elegant buildings were constructed in a variety of styles from coast to coast. The choice of style often reflected pre-war conventions based on building use. On university campuses convincing examples of collegiate Gothic were completed, extended or begun. Here too the result was a sense of continuity and unity with the past at Toronto (Hart House, Sproatt and Rolph, 1911-19, Soldier's Tower added 1924), at British Columbia (Science Building, Sharp and Thompson, 1914-25), at Saskatchewan and at McMaster (seeThompson, Berwick, Pratt and Partners).

The 1920s were also marked by a revival of the romantic Château-Baronial mode for great hotels. World famous resorts such as Château Lake Louise and the Banff Springs Hotel were extended and new hotels built in Vancouver (Hotel Vancouver, 1928-39) and Saskatoon (Bessborough, 1930-32), both designed by Archibald and Schofield. For public and especially commercial buildings, classical forms remained the style of choice (Sun Life Building, Montréal, Darling and Pearson, 1914-31), though by the 1930s the classical language was increasingly simplified almost to the point of abstraction. Sometimes termed "stripped classicism," good examples can be found in most cities, often in the form of banks such as John Lyle's Bank of Nova Scotia in Calgary (1929).

Domestic design too was dominated by a taste for elegant interpretations of past architectural styles. From Montréal's Westmount to Vancouver's Shaughnessy Heights the neighbourhoods of the wealthy provided a bucolic scene of Tudor gables, Georgian parapets, Italian terraces and Spanish arches set among carefully planted gardens.

For the middle classes the Californian bungalow remained popular while here and there could be seen the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright. An early example is the Ottawa work of Francis Sullivan (E.P. Connors House, Ottawa, 1914-15); somewhat later is the B.T. Lea House in Vancouver by John A. Pauw (1930).

The Jazz Age and New Styles

By the mid-1920s the post-war culture of the industrialized world had begun to generate a series of unified styles which affected fashion, design and architecture. These included Art Deco, Moderne, Expressionism and Functionalism. Overall there was widespread interest in new sources of inspiration ranging from the exotic and primitive to the industrial. Forms were simplified, composition more geometric and there was a general trend towards abstraction.

In this changing architectural climate, Romanesque emerged as a newly fashionable style, especially when used as a point of departure. At the Royal York Hotel, Toronto (Ross and Macdonald with Sproatt and Rolph, 1927-29) it was combined with a châteauesque roof. At the nearby 34-storey skyscraper for the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (York and Sawyer, with Darling and Pearson, 1929-31) the overall effect was more smoothly vertical and the interior ravishing.

At Holy Blossom Temple (Toronto, Chapman and Oxley with Maurice D. Klein, 1936-7) and St. James Anglican Church (Vancouver, Adrian Gilbert Scott with Sharp and Thompson, 1935-37) Romanesque is combined with an exposed concrete structure to create powerful, simplified forms very much of their time.

Canadian architecture had long been influenced by American and European architectural fashions and by the end of the 1920s Art Deco (a name drawn from the 1925 Paris Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes) had appeared. As in New York, skyscrapers were fertile ground.

Examples include the Aldred Building in Montréal (E.I. Barrott, 1929-31) and the Marine building in Vancouver (McCarter Nairne, 1929-30). But the fashion also appeared at the Toronto Stock Exchange (George and Moorhouse with S.H. Maw, 1936-37), in houses (Cormier House, Montréal, 1930) and department stores. In 1930 T. Eaton and Company invited French designer Jacques Carlu (then teaching at MIT) to design interiors for its stores in Montréal and Toronto.

During the 1930s and early 1940s architecture was also influenced by the streamlined effects of industrial design. The resulting style - surfaces of smooth stucco, rounded corners and horizontal accents - is often called "moderne." It was especially popular in the design of movie theatres (Varscona Theatre, Rule, Wynn and Rule, Edmonton, 1940) though its influence can be found in many buildings of the period.

National Expression

The complex nature of Canadian architecture during the 1920s and 1930s was particularly evident in Québec. There it was possible to see in clearest form the influence of yet another theme of the interwar years: the desire for new forms of cultural expression stimulated by social, religious, ethnic and national concerns. Undoubtedly, the leading architect in the province was Ernest Cormier (1885-1980). Trained as an engineer and architect, educated in Paris as well as Montréal, Cormier's work ranged from the refined art deco of his own house (Montréal, 1930), to seaplane hangars in thin shell concrete (Montréal, 1928) to the powerful, spreading forms of his chef d'oeuvre, the Université de Montréal (1924-43). This large campus dominates the northwestern flank of Mount Royal. Visible for miles around, its severe rectilinear massing and frank use of glass and brick was combined with an assured handling of detail and ornament to make it a powerful symbol of the shifting nature of Québec society.

The forms of the Université de Montréal seem poised between the radical simplicity of functionalism, a fashion which would soon dominate Canadian architecture, and the desire to use materials in an expressive, if abstract way for emotional effect. This expressionist tendency can also be seen in the work of Dom Paul Bellot and his followers. Bellot, a Belgian monk, whose work ranks among the masterpieces of European expressionism, was invited to lecture in Montréal in 1934. His ideas struck a chord among Catholic architects seeking an innovative architectural language. By 1939 Bellot had been appointed architect at Saint Joseph's Oratory, which was completed to his proposals, and had joined the design team for the Abbaye de Saint-Benoît-du-Lac (Mansonville, Québec). Bellot stimulated a school of ecclesiastical design whose first fruits included the Église Sainte-Thérèse-de-Lisieux by Adrien Dufresne (Beauport, Québec, 1936).

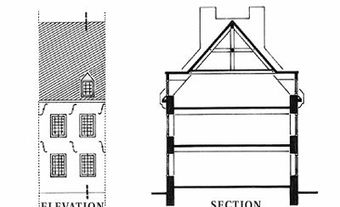

Paradoxically, while francophone Québec looked to an emerging modern culture for inspiration during the 1920s and 1930s, anglophones in the province focused on an examination and rediscovery of Québec's preindustrial past. Stimulated by the paintings of artists such as Clarence Gagnon and encouraged by architect/scholars Percy Nobbs and Ramsay Traquair at McGill University, many of Québec's most fashionable architects borrowed the fieldstone construction and pitched roofs of the traditional Québecois farmhouse in the development of a regionalist domestic style.

This was the Canadian manifestation of a continent-wide "regionalism" in domestic design, but the interest in and fashion for historical Québec forms was part of a larger nationalist current influencing Canadian architecture at that time. Outside Québec, the leading apologist for an overtly Canadian architecture was the Toronto architect John Lyle. In a series of articles and projects Lyle explored the possibilities of a Canadian decorative iconography (Runnymede Library, Toronto, 1929; Bank of Nova Scotia, Halifax, 1930).

In other parts of the country and especially the newly settled prairies, a folk architecture of adapted and transplanted forms had already begun to take shape. The result was work of charm and vigour whose scale ranks from the humble to the monumental (Church of the Immaculate Conception, Cook's Creek, Manitoba, 1930, Father Ruh, 1924-25).

Functionalism and the Modern Movement

By the mid-1930s European functionalism, an approach to architecture characterized by boxy shapes, sheets of glass, planar surfaces and a belief in the primacy of utility and function in overall design, had begun to influence Canadian architectural culture. However the lingering effects of a devastating economic depression and the lack of adventurous clients meant that only a handful of houses in the new style (sometimes referred to as the "international style") were built by 1940. These included the works of Marcel Parizeau and Robert Blatter in Québec and those of B.C. Binning, Peter Thornton, Robert Berwick and C.E. Pratt in Vancouver. Industrial buildings and the occasional commercial project also show evidence of the move to functionalism (Habitations Canada Cement, Barott, Marshall, Montgomery and Merrett, Architects, 1940).

The most dramatic effect of functionalism was felt in the universities. By the early 1940s decades of pedagogical tradition had been overturned as not just the functionalist style, but the ideology and modus operandi of the Modern Movement were introduced by John Bland at McGill, Eric Arthur at Toronto, and John Russell at Manitoba. After the war, veterans entered the universities in record numbers and this modernist orientation was intensified. All three schools of architecture together with the newly established school at the University of British Columbia hired professors trained in Modernist practice. Some came to Canada from Europe, others from American schools such as Harvard and MIT. By the early 1950s a generation of young modernist architects was entering the profession.

The career of John C. Parkin (1922-88) reflects this pattern. Educated at the University of Manitoba, Parkin left for Toronto and then graduate work under Walter Gropius at Harvard. He then returned to Toronto where, beginning with the headquarters building of the Ontario Association of Architects (1954), he designed a distinguished series of international style buildings. His employer, John B. Parkin (no relation) meanwhile established a comprehensive design firm ideally suited to the needs of corporate clients and offering every imaginable service from engineering to interior design, landscape, signage and of course architectural form (Aeroquay, Toronto-Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Toronto, 1957-65).

Modernism

By the mid-1950s Canadian architecture was a profession thoroughly imbued with a modernist sensibility. Its achievements and sphere of activity advanced on all fronts. These included an invigorated architectural press (The Canadian Architect, established 1957); experiments in suburban planning (Don Mills, Ontario, and Wildwood Park, Winnipeg); new towns such as Kitimat, British Columbia; a program of public housing sponsored by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation; and continual advances in building technology.

Pent-up demand for public buildings of all kinds as well as the prosperity of Canadian business meant a steady stream of commissions. The earliest centre of modernist production was Vancouver. There, a handful of architects explored the modernist language with notable success. Examples include the Vancouver Public Library (Semmens and Simpson, 1956-57) and the BC Electric building by Thomson, Berwick and Pratt (1955-57).

The city's striking landscape was also dotted with impressive domestic designs, especially those by two recent graduates: Ron Thom and Arthur Erickson. Other important centres included Winnipeg, especially the work of Green, Blankstein, Russell Associates (Winnipeg International Airport, with W.A. Ramsay, 1960) and Smith, Carter, Searle (School of Architecture, 1959) and Ottawa (Ottawa City Hall, Rother, Bland and Trudeau, 1958) and Toronto, where the much publicized new Toronto City Hall (Viljo Revell, 1961-65) signalled the utopian optimism of the era.

To sensitive observers it was already clear by 1960 that the impact of Modernism had led Canadian architecture to a self-confidence unique in its history. In hindsight this seems justified. Nowhere was this more the case than Montréal, a city on the verge of transformation leading to the 1967 International Exposition. The scale of what was to come was heralded by the construction of Place Ville Marie (I.M. Pei and Associates, Architect, Affleck, Desbarats, Dimakopoulos, Lebensold, Michaud, Sise, resident architects, 1958-65; see Arcop). What followed was a series of skyscrapers (Place Victoria, Luigi Moretti and Pier Luigi Nervi, Greenspoon, Freedlander and Dunne Architects, and Jacques Morin, Architect, 1961-65); public buildings (Place Bonaventure, Affleck, Desbarats, Dimakopoulos, Lebensold, Sise architects, R.T. Affleck partner in charge, 1963-67); and public infrastructure (Montréal Subway), which attracted attention around the world. The redevelopment of central Toronto was equally dramatic though somewhat later in time, beginning with the Toronto Dominion Centre (Mies van der Rohe consultant, John B. Parkin Associates and Bregman and Hamann construction, 1964-68).

Equally significant a feature of the later 1950s and 1960s was the appearance of a second stream of young practitioners whose work was often highly individual. Reacting against the perceived monotony of mainstream modernism, Roger d'Astous in Québec, Étienne Gaboury in Manitoba, Clifford Wiens in Saskatchewan, and Douglas CARDINAL in Alberta produced work which reflected a renewed concern with local culture.

In Toronto, the transplanted British Columbian Ron Thom brought his personal manner to Trent University and the University of Toronto (Massey College), while towering above his contemporaries was the increasingly important figure of Arthur Erickson. With his extraordinary plan for Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Erickson garnered international attention as a distinctive and powerful voice on the world stage.

See also Architectural History, Early First Nations; Architectural History, The French Colonial Régime; Architectural History, 1759-1867; Architectural History, 1867-1914; Architectural History, 1967-1997.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom