Alcan Incorporated was a major Canadian aluminum mining and manufacturing corporation. From the early 1990s to the early 2000s, it was the second-largest aluminum producer in the world. The company was originally founded in 1902 as the Northern Aluminum Company Limited, located in Shawinigan, Quebec. It was established as the Canadian subsidiary of the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa), one of the founders of which invented the process for extracting aluminum from bauxite. Northern Aluminum was renamed the Aluminum Company of Canada in 1925, and in 1928, it formally detached from Alcoa. In 1966, it was again renamed, this time as Alcan Aluminum Limited (becoming Alcan Incorporated in 2001). In 2007, Alcan was purchased by the British-Australian multinational corporation Rio Tinto for $38 billion. Today, Rio Tinto continues to operate several smelters in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec, as well as in Kitimat, British Columbia.

Background: How Is Aluminum Made?

After silicon, aluminum is the most abundant metallic substance in the Earth’s crust, accounting for about 8 per cent of its weight. However, whereas other metals (such as silver and gold) can sometimes be found in rich, highly concentrated geological formations, aluminum is typically mixed with a variety of other rocks and minerals. In addition, the element is often fused with oxygen to make aluminum oxide. Rock with high concentrations of aluminum is known as bauxite.

In 1886, Pittsburgh-based inventor Charles Hall and French inventor Paul Héroult independently developed the process for extracting aluminum from bauxite that is still in use today. The process involves heating bauxite to extract aluminum oxide, which is then dumped into a chemical solution and charged with a high-voltage electrical current. For the first time in history, aluminum could now be mass-produced and made commercially available.

Alcoa and the Northern Aluminum Company

In 1888, Charles Hall and businessman Arthur Davis founded the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, which later became the Aluminum Company of America, or Alcoa. Aluminum, as a relatively light and corrosion-resistant metal, proved valuable for the production of several commodities including bicycle parts, car parts, lithographic plates and cooking utensils. Pure aluminum is also highly conductive and has been used to make electrical cables since the late 1800s.

Despite aluminum’s growing market applications, Alcoa struggled to find an affordable source for the large quantities of electricity required in the extraction process. In its first eight years, it moved its factory from Pittsburgh to New Kensington, Pennsylvania, and then to Niagara Falls, New York.

Hall and Davis soon decided to expand their manufacturing operations into Canada, and in 1899, they began constructing an aluminum smelter and hydroelectric generator in Shawinigan, Quebec.

Three years later, the partners established the Northern Aluminum Company Limited, as the Canadian subsidiary of Alcoa. Hall and Davis were registered as executive officers of the new company, while Pittsburgh banker Richard Mellon was appointed its president.

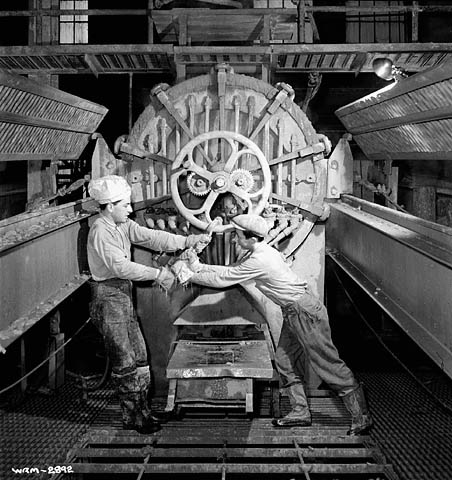

Shortly after beginning operations, the Shawinigan plant was producing thousands of pounds of aluminum per day, and shipping the product to markets in Europe and Japan.

First World War

During the First World War, demand for aluminum grew substantially as a result of increased production of firearms, explosives and airplanes. Northern Aluminum stepped up its operation in Shawinigan to meet this demand, and in 1919 they established a casting plant in Toronto.

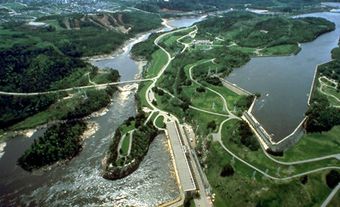

Throughout the interwar years, the company pursued a strategy of integrating its technical operations in order to reduce costs. In the 1920s, it purchased the Saguenay Power Company, eventually bringing a total of six power stations on the Saguenay River under its control — at the time the largest private holding of hydroelectric infrastructure in the world. The company also gained control of the transportation networks it relied on, including ports and railroads in the Saguenay region.

Around the same time, Arthur Davis concluded that Alcoa should reorganize its non-US operations under a separate company, and in 1928, Northern Aluminum formally detached from its American parent to become Aluminum Limited. In 1929, the company moved its Canadian regional offices from Toronto to Montreal, and by 1939 these offices had become Limited’s main headquarters. Two years later, the company also opened an international office in Geneva, Switzerland.

Aluminum Limited remained closely associated with Alcoa in the subsequent decades, however. The shares of both companies belonged to the same people, and from 1928 until 1947, the Canadian company was led by Davis’s younger brother, Edward.

Aluminum Limited took immediate possession of most of Alcoa’s international mining and manufacturing operations, and would gain a controlling stake in several others in the subsequent years. By 1934, it owned or controlled several operations throughout the world, including a bauxite mine in British Guiana, a factory in England, multiple operations in India and others in Italy and Norway.

Second World War–2007 Rio Tinto Purchase

When the Second World War began, Aluminum Limited’s Canadian operations possessed approximately three-quarters of the production capacity for aluminum in the British Empire. As the Allies’ demand for the metal grew, Aluminum Limited expanded rapidly. According to Isaiah Litvak and Christopher Maule, authors of a 1977 federal report on Alcan, “The company’s growth between 1937 and 1944 was dramatic: assets increased fivefold; sales increased fivefold; net income increased sixfold.”

This rapid expansion was assisted to a large extent by the British, Canadian, American and Australian governments, which extended cheap loans to the company and deferred many of its taxes.

In 1946, Aluminum Limited’s sales fell to less than half of what they had been two years earlier, and its productive infrastructure suddenly outsized its market. The company’s new challenge was to maintain its integrated supply networks while at the same time expanding its range of finished and semi-finished products.

Sales rebounded substantially in the subsequent years, however, as aluminum was increasingly used by the construction business, electrical utilities and other manufacturers.

Aluminum Limited invested in expanding its infrastructure throughout the 1950s, opening three new hydroelectric plants in the Saguenay system, as well as a massive new smelter in Kitimat, British Columbia. Simultaneously, Aluminum Limited also invested in the development of bauxite extraction in Jamaica, which possessed rich and hitherto untapped reserves of the material.

The aluminum industry also became slightly more competitive around this time. A court ruling issued in June 1950 found Alcoa and Aluminum Limited to be an effective monopolist, and under US antitrust law ordered that shareholders sell their shares in either Aluminum Limited or Alcoa. Throughout the subsequent decade, American companies Kaiser and Reynolds also gained market share.

In spite of these developments, the privileged position of Aluminum Limited (known as Alcan starting in 1966) in the aluminum market was hardly challenged in the subsequent decades. Given that it owned virtually all the components of the production process, the company could produce metal more cheaply and on a larger scale than virtually any of its rivals.

In 2007, Alcan was bought by the British-Australian mining company Rio Tinto. The subsidiary became known as Rio Tinto Alcan, but in 2015, Rio Tinto decided to drop Alcan from the name.

Labour Issues

Rio Tinto’s aluminum operations have come under considerable stress since 2007. The emergence of Chinese-produced aluminum began to lower the price of the metal only months after the company bought Alcan, and Rio Tinto has consequently attempted to scale back its labour costs as much as possible.

The job cuts generated considerable tensions, especially in Quebec. In December 2011, the company locked out all 780 workers at its smelter in Alma. At the time, the company was trying to establish a new collective agreement with the union that would allow them to replace retiring workers with cheaper subcontractors — a concession the union opposed. The lockout ended in July 2012, when the two sides reached an agreement that limited the company’s ability to outsource labour.

Responding to market pressures and new environmental regulations, Rio Tinto also permanently closed its smelters in Beauharnois and Shawinigan, Quebec in 2009 and 2013, respectively. Combined with a round of layoffs at its Montreal offices in 2015, these moves left over 800 Quebecers out of work.

Environmental Issues

The upgrade to Rio Tinto’s smelter in Kitimat, British Columbia, first announced in 2007, was criticized by environmentalists. Although the new facility reduced Kitimat’s emissions of greenhouse gases by approximately 50 per cent, it also involved a substantial increase of the plant’s emissions of sulphur dioxide — a gas that is known to cause breathing problems, cardiovascular disease, and damage to plant life.

In April 2013, the BC Ministry of the Environment issued a permit allowing the plant to increase sulphur dioxide emissions from 27 to 42 tonnes per day. Local residents challenged the permit in court, demanding that the company install “scrubbers” that would reduce sulphur dioxide emissions. Doing so would have cost the company between $100 million and $200 million. In December 2015, the BC Environmental Appeal Board upheld the original permit.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

_IMO_9785756,_Maasmond_pic.jpg)