Working-class history is the story of the changing conditions and actions of all working people. Most adult Canadians today earn their living in the form of wages and salaries and thus share the conditions of dependent employment associated with the definition of "working class." The Canadian worker has been a neglected figure in Canadian history and, although Canadians have always worked, working-class history has received little attention. Until recently, the most common form of working-class history has been the study of the trade union, or labour, movement (unions are organizations formed by workers in order to strengthen their position in dealing with employers and sometimes with governments).

Although the development of organized labour provides a convenient focus for the discussion of working-class history, it is important to remember that most working people, past and present, have not belonged to unions: in 1996 only 33.9% of all nonagricultural paid workers in Canada belonged to unions. However, because unions have often pursued goals designed to benefit all workers, the labour movement has won a place in Canadian society.

Canadian workers have contributed in many ways to the development of Canadian society, but the history of working people, in their families, communities and work places, is only gradually becoming part of our view of the Canadian past. Canadian historians have often studied the various Canadian cultural and regional identities, but the working-class experience is now proving to be one of the unifying themes in Canadian history (see Work).

English Canada

The working class emerged during the 19th century in English Canada as a result of the spread of industrial capitalism in British North America. At the time, it was common for many Canadians to support themselves as independent farmers, fishermen and craftworkers. Entire families contributed to the production of goods (see History of Childhood). The growing differentiation between rich and poor in the countryside, the expansion of resource industries (see Resource Use), the construction of canals and railways, the growth of cities and the rise of manufacturing all helped create a new kind of work force in which the relationship between employer and employee was governed by a capitalist labour market and where women and children no longer participated to as great an extent.

Company towns, based on the production of a single resource such as coal, emerged during the colonial period and provided a reserve of skilled labour for the company and a certain degree of stability for the workers. When violence erupted, the companies' responses varied from closing the company-owned store to calling in the militia. Domestic service (servants, housekeepers, etc) emerged as the primary paid employment for women.

Child labour reached its peak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, supplemented by immigrant children brought from Britain by various children's aid societies. The workers were often cruelly exploited, and for any worker, job security and assistance in the event of illness, injury or death were almost nonexistent.

For most of the 19th century, unions were usually small, local organizations. Often they were illegal: in 1816 the Nova Scotia government prohibited workers from bargaining for better hours or wages and provided prison terms as a penalty. Nevertheless, workers protested their conditions, with or without unions, and sometimes violently. Huge, violent strikes took place on the Welland and Lachine canals in the 1840s. Despite an atmosphere of hostility, by the end of the 1850s local unions had become established in many Canadian centres, particularly among skilled workers such as printers, shoemakers, moulders, tailors, coopers, bakers and other tradesmen.

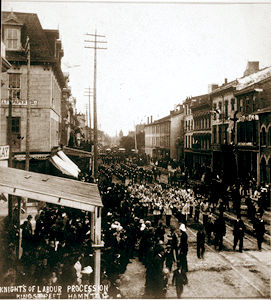

The labour movement gained cohesiveness when unions created local assemblies and forged ties with British and American unions in their trade. In 1872 workers in Ontario industrial towns and in Montréal rallied behind the Nine-Hour Movement, which sought to reduce the working day from up to 12 hrs to 9 hrs. Hamilton's James Ryan, Toronto's John Hewitt and Montréal's James Black led the workers. Toronto printers struck against employer George Brown, and in Hamilton, on 15 May 1872, 1500 workers paraded through the streets.

The ambitiously titled Canadian Labor Union, formed in 1873, spoke for unions mainly in southern Ontario. It was succeeded in 1883 by the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada, which became a lasting forum for Canadian labour. In Nova Scotia the Provincial Workmen's Association (1879) emerged as the voice of the coal miners and later spoke for other Maritime workers.

The most important organization of this era was the Knights of Labor, which organized more than 450 assemblies with more than 20 000 members across the country. The Knights were an industrial union which brought together workers regardless of craft, race (excepting Chinese) or sex. Strongest in Ontario, Québec and BC, the Knights were firm believers in economic and social democracy, and were often critical of the developing industrial, capitalist society. Key Knights included A.W. Wright, Thomas Phillips Thompson and Daniel J. O'Donoghue.

By the late 19th century the "labour question" had gained recognition. The Toronto printers' strike of 1872 led PM Sir John A. Macdonald to introduce the Trade Unions Act, which stated that unions were not to be regarded as illegal conspiracies. The Royal Commission on the Relations of Labour and Capital, which reported in 1889, documented the sweeping impact of industrialization in Canada, and the commissioners strongly defended unions as a suitable form of organization for workers: "The man who sells labor should, in selling it, be on an equality with the man who buys it." Another sign of recognition came in 1894 when the federal government officially adopted Labour Day as a national holiday falling on the first Monday in September.

The consolidation of Canadian capitalism in the early 20th century accelerated the growth of the working class. From the countryside, and from Britain and Europe, hundreds of thousands of people moved to Canada's booming cities and tramped through Canada's industrial frontiers (see Bunkhouse Men). Most workers remained poor, their lives dominated by a struggle for the economic security of food, clothing and shelter; by the 1920s most workers were in no better financial position than their counterparts had been a generation earlier.

Not surprisingly, most strikes of this time concerned wages, but workers also went on strike to protest working conditions, unpopular supervisors and new rules, and to defend workers who were being fired. Skilled workers were particularly alarmed that new machinery and new ideas of management were depriving them of some traditional forms of workplace authority.

Despite growing membership, divisions appeared between unions, and this limited their effectiveness. The most aggressive organizers were the craft unions, whose membership was generally restricted to the more skilled workers. Industrial unions were less common, though some, such as the United Mine Workers, were important. The American Federation of Labor (founded 1886, see AFL-CIO) unified American craft unions and, under Canadian organizer John Flett, chartered more than 700 locals in Canada between 1898 and 1902; most were affiliated with the TLC. At the TLC meetings in 1902 the AFL craft unions voted to expel any Canadian unions, including the Knights of Labor, in jurisdictional conflict with the American unions, a step which deepened union divisions in Canada.

The attitudes of government were also a source of weakness. Though unions were legal, they had few rights under the law. Employers could fire union members at will, and there was no law requiring employers to recognize a union chosen by their workers. In strikes employers could ask governments to call out the troops and militia in the name of law and order, as happened on more than 30 occasions before 1914 (see, for example, Fort William Freight Handlers Strike).

With the creation of the Department of Labour in 1900, the federal government became increasingly involved in dispute settlement. The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act (1907), the brainchild of William Lyon Mackenzie King, required that some important groups of workers, including miners and railwaymen, must go through a period of conciliation before they could engage in "legal" strikes. Since employers were still free to ignore the unions, dismiss employees, bring in strikebreakers and call for military aid, unions came to oppose this legislation.

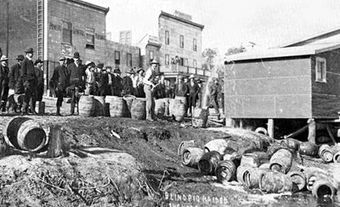

One of the most important developments in the prewar labour movement was the rise of revolutionary industrial unionism, an international movement which favoured the unification of all workers into one labour body to overthrow the capitalist system and place workers in control of political and economic life. The Industrial Workers of the World, founded in Chicago in 1905, rapidly gained support among workers in western Canada such as navvies, fishermen, loggers and railway workers. The "Wobblies" attracted nationwide attention in 1912 when 7000 ill-treated immigrant railway workers in the Fraser Canyon struck against the Canadian Norther Railway. A number of factors, including government suppression, hastened its demise during the war.

WWI had an important influence on the labour movement. While workers bore the weight of the war effort at home and paid a bloody price on the battlefield, many employers prospered. Labour was excluded from wartime planning and protested against Conscription and other wartime measures. Many workers joined unions for the first time and union membership grew rapidly, reaching 378 000 in 1919. At the end of the war strike activity increased across the country: there were more than 400 strikes in 1919, most of them in Ontario and Québec.

Three general strikes also took place that year, in Amherst, Nova Scotia, Toronto and Winnipeg. In Winnipeg the arrest of the strike leaders and the violent defeat of the strike demonstrated that in a labour conflict of this magnitude the government would not remain neutral (see Winnipeg General Strike). In 1919 as well, the radical One Big Union was founded in Calgary, raised from the ashes of the IWW. It soon claimed 50 000 members in the forestry, mining, transportation and construction industries.

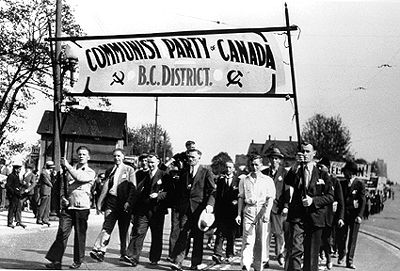

Despite the formation of the OBU and the Communist Party of Canada, the 1920s remained a period of retreat for organized labour. The exception was the coal miners and steelworkers of Cape Breton Island, who, led by J.B. McLachlan, rebelled repeatedly against one of the country's largest corporations (see Cape Breton Strikes, 1920s).

The 1930s marked an important turning point for workers. The biggest problem of the decade was unemployment. In the depths of the Great Depression more than one million Canadians were out of work, about one in 4 workers. Emergency relief was inadequate and was often provided under humiliating conditions (see Unemployment Relief Camps). Unemployed workers' associations fought evictions and gathered support for employment insurance, a reform finally achieved in 1940.

One dramatic protest was the On to Ottawa Trek of 1935, led by the former Wobbly Arthur "Slim" Evans, an organizer for the National Unemployed Workers' Association. The Depression demonstrated the need for workers' organizations, and by 1949 union membership exceeded one million workers. Much of the growth in union organization came in the new mass-production industries among workers neglected by craft unions: rubber, electrical, steel, auto and packinghouse workers.

The communist-supported Workers Unity League (1929-36) had pioneered industrial unionism in many of these industries. The Oshawa Strike (8-23 August 1937), when 4000 workers struck against General Motors, was among the most significant in establishing the new industrial unionism in Canada. Linked to the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the US, many of the new unions were expelled by the TLC and formed the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) in 1940.

Early in WWII the federal government attempted to limit the power of unions through wage controls and restrictions on the right to strike (see Wartime Prices and Trade Board; National War Labour Board), but many workers refused to wait until the war was over to win better wages and union recognition. Strikes such as that of the Kirkland Lake gold miners in 1941 persuaded the government to change its policies. In January 1944 an emergency order-in-council, PC 1003, protected the workers' right to join a union and required employers to recognize unions chosen by their employees. This long-awaited reform became the cornerstone of Canadian industrial relations after the war, in the Industrial Relations and Disputes Investigation Act (1948) and in provincial legislation.

At the end of the war a wave of strikes swept across the country. Workers achieved major improvements in wages and hours, and many contracts incorporated grievance procedures and innovations such as vacation pay. Some industry-wide strikes attempted to challenge regional disparities in wages. The Ford strike in Windsor, Ontario, between September 12 and 29 December 1945, began when 17 000 workers walked off the job. The lengthy, bitter strike resulted in the landmark decision by Justice Ivan C. Rand, which granted a compulsory check-off of union dues (see Rand Formula; Windsor Strike). The check-off helped give unions financial security, though some critics worried that unions might become more bureaucratic as a result.

By the end of the war Canadian workers also had become more active politically. The labour movement had become involved in politics after 1872 when the first workingman (Hamilton's Henry Buckingham Witton) was elected to Parliament as a Conservative candidate, as was A.T. Lépine, a Montréal leader of the Knights of Labor in 1888. In 1874 Ottawa printer D.J. O'Donoghue was elected to the Ontario legislature as an independent labour candidate. Labour candidates and workers' parties were often backed by local unions. In 1900 A.W. Puttee, a Labour Party founder, and Ralph Smith TLC president, were elected to Parliament. The Socialist Party of Canada appealed to the radical element and elected members in Alberta and BC. During the war, policies such as conscription encouraged unions to increase their political activity at the provincial and federal levels. In the 1921 federal election, labour candidates contested seats in all 9 provinces; OBU general secretary R.B. Russell was defeated, as was Cape Breton's J.B. McLachlan, but Winnipeg's J.S. Woodsworth and Calgary's William Irvine were elected.

The social catastrophe of the Great Depression increased the appeal of radical politics; Communist Party support increased, and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation was founded. During the 1940s the CCF became the official opposition in BC, Ontario and Nova Scotia, and in 1944 the first CCF government was elected in Saskatchewan. By the late 1940s the CCF and the Communist Party had a combined membership of 50 000.

The new rights of labour and the rise of the welfare state were the decisive achievements of the 1930s and 1940s, promising to protect Canadian working people against major economic misfortunes. The position of labour in Canadian society was strengthened by the formation of the Canadian Labour Congress (1956), which united the AFL and the Canadian Congress of Labour and absorbed the OBU. The CLC was active in the founding of the New Democratic Party, and, despite the emergence of rival union centrals such as the Confederation of Canadian Unions (1975) and the Canadian Federation of Labour (1982), it continues to represent more than 60% of union members.

Steady growth in government employment during this period meant that by the 1970s one in 5 workers was a public employee. With the exception of Saskatchewan, which gave provincial employees union rights in 1944, it was not until the mid-1960s, following an illegal national strike by postal workers (see Postal Strikes, CUPW), that public employees gained collective bargaining rights similar to those of other workers. In 1996, 3 of the 6 largest unions in Canada were public-service unions , whose growth has increased the prominence of Canadian over American-based unions in Canada, more than 60% of whose members belong to Canadian-based unions. Several major industrial unions, including the Canadian Auto Workers, reinforced this trend by separating from their American parent unions.

Another significant change has been the rise in the number of female workers. By 1996, the female labour force participation rate was over 59%. Women made up 45% of the labour force and more than 40% of union membership. The change was reflected in the growing prominence of women union leaders and in concern over issues such as maternity leave, child care, sexual harrassment and equal pay to women workers for work of equal value.

Despite the achievements of organized labour, the sources of conflict between employers and employees have persisted. Determined employers have been able to resist unions by using strikebreakers and by refusing to reach agreement on first contracts. Workers have continued to exert little direct influence over the investment decisions that govern the distribution of economic activity across the country. In collective agreements such issues as health, safety and technological change have received greater attention, but the employer's right to manage property has predominated over the workers' right to control the conditions and purposes of their work.

Governments have often acted to restrict union rights: on occasion, as in the 1959 Newfoundland Loggers' Strike, individual unions have been outlawed, and since the 1960s and 1970s governments have turned with increasing frequency to the use of legislated settlements, especially in disputes with their own employees. Despite the intervention of the welfare state, many workers have continued to suffer economic insecurity and poverty.

The capitalist labour market has failed to provide full employment for Canadian workers, and since the 1980s more than one million Canadians are regularly reported unemployed; especially in underdeveloped regions such as Atlantic Canada, many workers have continued to depend on part-time, seasonal work and to provide a reserve pool of labour for the national economy. Most working people today are more secure than their counterparts were in the 19th century, but many workers feel threatened today by pressures arising from the globalization of the economy and new employer strategies to reduce labour costs.

Québec

As in other parts of Canada, the history of working-class Québec has only recently received serious study, and research has concentrated on the trade-union phenomenon. Before the industrialization of Québec(about 1870-80), most businesses were small and crafts-oriented. In 1851 there were only 37 companies employing more than 25 workers. Salaried employees were rare, although there were some in the timber trade, construction, and canal and railway earthworks.

Québec trade unionism began in the early decades of the 19th century when skilled craftsmen established weak, localized and ephemeral organizations. Montréal craft unions united 3 times in larger associations: in 1834, to win a 10-hour day; in 1867, to form the Grand Association; and in 1872, to win a 9-hour day. But each lasted only a few months and few unions withstood the 1873 economic crisis. Québec workers gave other signs of their presence as well. There were at least 137 strikes from 1815 to 1880. The co-operative movement, through life and health mutual-assurance funds, expanded rapidly after 1850 among the working class. These early signs of worker consciousness demonstrate the workers' desire to create alliances in response to the insecurities of factory work and urban life, and also the workers' rejection of the capitalist labour market in which they were treated as commodities.

Manufacturing activities overtook commerce around 1880 and the interests of the industrial bourgeoisie framed the state policies. Montreal's population doubled between 1871 and 1891, as the city became Canada's industrial and financial capital. As the number of workers increased, more solid craft unions grew under the leadership of international unions coming from the US. These unions brought the system of collective bargaining whereby wages, workload, hours of work and the rules of apprenticeships were negotiated with employers and recorded in a written document. In the 1880s a very different American influence, the Knights of Labor, made inroads among both skilled and unskilled workers. Unlike international unions which stressed the economic betterment of members through collective bargaining, they proposed a total reform of industrial society, including the abolition of wage-earning and the introduction of co-operatives and small-scale ownership.

Their activities helped in the formation of central workers' councils in Montréal (1886) and Québec City (1890). They channeled union demands to city councils as the TLC, which Québec unions affiliated from 1886, directed legislative reforms to federal and provincial governments. These organizations gave workers a political voice which, in the period 1886-1930, called for electoral reform, free and compulsory education, social programs and the nationalization of public utilities. Their demands expressed a labourist "projet de société" envisaging the reform rather than the abolition of capitalism.

The international unions grew quickly at the beginning of the century and they wiped out the Knights of Labor. They had over 100 locals in 1902 with a membership of about 6000. But their dominance was not unchallenged. First national unions hoped to establish a truly Canadian movement and expanded throughout Canada, but they failed to attract many workers. The greatest challenge for international unions came from the Catholic unions set up by the clergy from 1907. The socialist and anticlerical leanings of the international unions were feared. The Catholic unions established a central in 1921 (Canadian and Catholic Confederation of Labour) and gradually adopted many of the methods and principles of international unionism. But they failed to attract more than a quarter of unionists in Québec, the bulk of the movement remaining loyal to international unions (see Social Doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church; Confederation of National Trade Unions).

In 1931, with a total membership of approximately 72 000, the union density in the province was about 10%, a percentage comparable to Ontario. They were mainly skilled workers in railways, building and some manufacturing industries. During WWII Québec was hit by a wave of unionization of semi-skilled and unskilled workers in mass production industries. Catholic unions had already unionized some of these workers but the main inroad came from international unions affiliated with the CIO. They provided a strong stimulus to union density that rose to 20.7% in 1941 and to 26.5% in 1951. Unionization was also bolstered by job shortages during the war and a new legal framework. Inspired by the American Wagner Act, the Labor Relations Act of 1944 became the cornerstone of private labour relations in Québec. It protects and favours the right of workers to collective bargaining.

Unions played a large role as critics of the conservative Duplessis government in the 1950s. Not only did they fight numerous pieces of legislation to restrict their activities, but they promoted in the population an active role for the Québec government. In this way they were among the main architects of the Quiet Revolution. In the 1950s international unions accounted for about 50% of union membership and about 30% for Catholic unions. The Catholic central changed its title in 1960 to the Confederation of National Trade Unions (CNTU).

The mid-1960s saw the expansion of unionism in the public sector (federal, provincial and municipal) and the para-public sector (teachers, health care workers). People were unhappy with their wages and working conditions, which were falling far behind the private sector, and were touched by the general climate of social change aroused by the Quiet Revolution. Their illegal strikes in 1963 and 1964 led the Québec government to grant the right to bargain and the right to strike to all civil servants, teachers and hospital workers. Their unionization gave a boost to union density that grew from 30.5% in 1961 to 37.6% in 1971.

Their influx transformed the union movement, which radicalized in the 1960s and 1970s. The province became the region with the highest rate of strikes in Canada, and the three main union centrals developed harsh criticism of the capitalist system. From 1972, all employees in the public and para-public sectors negotiated jointly every four years with the provincial government in "Common Front." This strategy, punctuated sometimes by general or sector strikes, improved the union bargaining power and working conditions of these employees.

The union movement suffered from the deep economic recession of 1981-82 and the high unemployment that followed. It underwent a dramatic change in rhetoric and strategy, giving up its global condemnation of the capitalist system and promoting "conflicting concertation" with management. The level of strikes, the highest in Canada during the 1970s, fell gradually in the next decade to below the Canadian average of working days lost per employee. The public and para-public employees who were at the forefront of union militancy lost their strength under the threat of repressive legislation. Nevertheless, union density remained high, around the 40% mark. Finally, the nationalism of the three union centrals evolved toward a clear support for the political independence of Québec, particularly after the failure of the Meech Lake Accord in 1989. They were the main social group behind the "yes" side in the tight Quebec referendum of 1995.

Historiography

Each period in the recording of Canadian labour history paralleled specific concerns that grew out of the practical struggles of the time. In 19th- and early 20th-century Canada, workers were not prominent subjects of scholarly production. Royal commissions provided copious evidence of the conditions of work and of labour's attempts to organize, and a few advocates of the working class offered their evaluations of Canadian workers' emergence as a social and political force. But concern with workers was a pragmatic one with explicit political purposes, and when studies were commissioned, as with, for example, R.H. Coats's 1915 examination of the cost of living, they were related directly to the perceived needs of the moment.

Between 1929 and 1945 in Britain and the US the study of labour history was channelled into examinations of political activity, the growth and consolidation of unions, and the gradual winning of collective bargaining rights, improved wages and better conditions. In Canada, individuals associated with an emerging social-democratic milieu had similar concerns and were advocates of public ownership, an active state and the preservation of civil liberties.

Leading this moderate socialist contingent was historian Frank Underhill, and associated with him were social scientists, economists and researchers at both McGill University and the University of Toronto, including Frank Scott, Eugene Forsey and Stuart Jamieson. Forsey eventually produced Trade Unions in Canada 1812-1902 (1982), an important overview of the institutional development of Canadian unionism in the 19th century, and Jamieson published Times of Trouble (1968), a government-commissioned monograph on strike activity over the period 1900-66. But in the 1930s and 1940s such figures played a more political role, sustaining the League for Social Reconstruction and helping the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation.

Often it seemed as though the academic advocates of socialism regarded workers as the passive recipients of the social reform intellectuals sought to stimulate. Those associated with social-democratic thought eased labour into scholarly discourse and defined the character of working-class studies. They regarded the labour movement as one of the forces upon which they could rely for support, but they had little intrinsic interest in labour as a class. The study of labour thus encompassed concern with unions, with labour's political activity, and with extolling the appropriate and humane leadership and reforms that only the CCF could offer.

After WWII labour history first began to be written in Canadian universities. Often, especially among professional historians, it was a by-product of other concerns. "George Brown, Sir John Macdonald, and the 'Workingman' " in the Canadian Historical Review (1943), by Donald Creighton, indicated how concerns with central political figures might provide a footnote to labour's as-yet untold story. D.C. Masters's The Winnipeg General Strike (1950) was purportedly part of a projected exploration of Social Credit in Alberta. J.I. Cooper published "The Social Structure of Montréal in the 1850s" in the Canadian Historical Association's Annual Report (1956), which took a preliminary step toward the exploration of workers' everyday lives.

Most studies of Canadian workers were not actually done by historians. Political scientist Bernard Ostry wrote on labour and politics of the 1870s and 1880s. The most innovative work came from economist and economic historian H.C. Pentland (Labour and Capital in Canada (1650-1860), 1981), whose studies challenged conventional wisdom, and from literary critic Frank Watt. They argued that labour had posed a fundamental criticism, through physical struggles and journalistic attacks on monopoly and political corruption, of 19th- and early 20th-century Canadian society well before the upheaval at Winnipeg and the appearance of the Social Gospel and the CCF.

Such studies probably had less force in the universities than among historically minded associates of the Communist Party such as Bill Bennett and Stanley Ryerson, who penned histories of early Canada and Canadian workers. Within the established circles of professional historians Kenneth McNaught exerted a far greater influence. McNaught was a product of the social-democratic movement of the 1940s, and attained significance not so much for what he wrote - which, in labour history, was rather limited - but because he taught a number of graduate students who pushed labour history into prominence in the 1970s.

McNaught's work stressed the importance of leadership in the experience of Canadian workers, and he was drawn to the institutional approach of labour-economist Harold Logan. Logan had been active in teaching and writing labour economics since the 1920s, and he produced the first adequate overview of Canadian trade-union development in Trade Unions in Canada (1948). His writing in the 1930s and 1940s emphasized the struggle within the Canadian labour movement between CCF followers and associates of the Communist Party.

Logan's arguments against communism, together with the practical confrontations of the period, molded social-democratic intellectuals in specific ways: for example, anti-Marxism (equated with opposition to the Stalinist Communist Party) was forever embedded in their approach to Canadian labour. Their horizons seemed bounded by the study of institutions, social reform and the question of proper leadership of the progressive movement and labour itself. McNaught's A Prophet in Politics (1959), which was a biography of J.S. Woodsworth, father of Canadian social democracy and a central figure in the history of radicalism, was the exemplary study in this genre.

In 1965 Stanley Mealing published "The Concept of Social Class in the Interpretation of Canadian History" (Canadian Historical Review, 1965). He concluded that little historical work in Canada had been directed toward workers' experience and that the main interpretive contours of our history would not be dramatically altered by attention to class. Important studies of the Communist Party, the CCF-NDP, early radicalism and labour's general political orientation soon appeared.

By the early 1970s studies of such major working-class developments as the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the consolidation of the AFL before WWI, western labour radicalism and the Winnipeg General Strike were underway or had appeared in print. They were followed by examinations of the One Big Union, the government response to immigrant radicalism, and conditions of life and labour in early 20th-century Montréal.

Leading figures in this proliferation of working-class studies were Irving Abella, David Bercuson, Robert Babcock, Ross McCormack and Donald Avery. Their work, in conjunction with labour studies undertaken by social scientists such as Paul Phillips, Martin Robin, Leo Zakuta, Gad Horowitz and Walter Young, as well as historians Desmond Morton and Gerald Caplan, served to establish labour history as a legitimate realm of professional historical inquiry. Their labour histories were written, perhaps unconsciously, out of the social-democratic concerns of the 1940s: leadership, decisive events, conditions demanding reform, the nature of ideology and the evolution of particular kinds of unions. Labour-history courses were taught for the first time, a committee of the Canadian Historical Association was created, and a journal, Labour/Le Travailleur, was launched in 1976. In 1980 Desmond Morton and Terry Copp published Working People, an illustrated history of Canadian workers. The 1970s and 1980s also saw a growing number of popular histories of unions.

After 1975 a new group of historians emerged, influenced less by the social democracy of the 1940s and more by the Marxism of the late 1960s and early 1970s. These historians were first struck with the general importance of theory, and looked to a series of debates within Western Marxism after 1917 for the nature of class structure and the character of subordination of the working class in capitalist societies.

Second, many drew inspiration from American and British studies (by E.P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, David Montgomery and Herbert Gutman) that appeared in the 1960s and heralded a break with earlier histories of labour. Finally, the emergence of women's history provided a third and complementary influence, which forced consideration of the process through which labour was reproduced in the family and was socialized into a particular relationship to structures of authority and work.

Generally speaking, those who were fashioning labour history in the early 1980s were united in their commitment to write the social history of the working class. If labour's institutions, political activities and material conditions of life were of essential importance in this broad social history, so too were hitherto unexplored aspects of the workers' experience: family life, leisure activities, community associations, and work processes and forms of managerial domination affecting both the evolution of unions and the lives of unorganized workers.

In all of this work there is a concern with working-class history as an analysis of the place of class in Canadian society. Class was conceived as a reciprocal, if unequal, relationship between those who sell their labour and those who purchase it. Some studies have concentrated on the structural, largely impersonal, dimensions of class experience (the size of working-class families, the numbers of workers associated with particular sectors of the labour market, the rates of wages and levels of unemployment), whereas other works unearthed the cultural activities of workers and the conflicts they have waged at the work place or in the community. Finally, this group was generally less willing to immediately dismiss the radicalism associated with Communist and socialist union activists.

Some published works by this generation of historians - including Joy Parr's Labouring Children (1980), an examination of the labouring experiences of pauper immigrant children; Bryan Palmer's A Culture in Conflict (1979), a discussion of skilled labour in Hamilton in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; Gregory Kealey's Toronto Workers Respond to Industrial Capitalism 1867-1892 (1980), a similar study of Toronto workers; and "Dreaming of What Might Be" (1982), an examination of the Knights of Labor in Ontario, 1880-1900, by Kealey and Palmer - attempt detailed explorations of working-class experience.

A host of articles and postgraduate theses attest to the treatment of subjects that a previous labour history never envisaged: ritualistic forms of resistance, patterns of craft inheritance among shoemakers, the place of the family economy in Montréal in the 1870s and 1880s, the riotous behaviour of early canallers, the significance of the life cycle among Québec cotton workers, 1910-50, the effects of mechanization and skill-dilution upon metalworkers in the WWI era, the nature of life in coal communities, or the role of literacy, housing, tavern life and the oral tradition among specific groups of workers. While those defending the traditional institutional approaches saw the new emphasis on culture as leading away from politics, this was not the intention of writers drawing from social history. Rather, they believed that working-class culture, however imprecise an idea initially, was intimately connected to other vital areas of labouring life such as unions and parliamentary politics.

With an increasing number of graduate students and professional historians taking up these subjects, the labour history of the late 1980s and early 1990s both revisited familiar themes and charted new directions. Detailed statistical research charting the major waves of workplace conflict has proceeded alongside explorations into the histories of the labour movement in many urban areas. Bushworkers and Bosses (1987), Ian Radforth's study of loggers and technological change in Northern Ontario, The New Day Recalled (1988), Veronica Strong-Boag's account of women between the wars, and Working in Steel (1988), Craig Heron's examination of steelworkers, have filled in notable gaps in the historical record, as has research on miners across Canada, the Depression-era relief camp workers, and many articles and monographs on skilled artisans. This work has contributed to the record of union growth and economic change, in particular with the transformation of labour processes in the workplace. Inquiries into the particular dilemmas of immigrant workers - Eastern Europeans, Italians, Jews - have also advanced our understanding of workers' social and cultural worlds. Two such studies are Franca Iacovetta's Such Hardworking People (1992) and Ruth Frager's Sweatshop Strife (1992).

An important part of the "new" working-class history takes issue with the regional stereotypes that figured so prominently in earlier studies. In particular, "western exceptionalism" - the idea that western Canadian workers were more radical than their eastern counterparts - has been challenged through research into the activities of socialists, syndicalists and Communists in central and Atlantic Canada. Recent studies by Mark Leier, entitled Red Flags and Red Tape (1995), and Robert McDonald, with Making Vancouver (1996), have also begun to question the extent and nature of radicalism in the west, instead pointing to the diversity of political beliefs among both skilled craftsmen in urban centres and unskilled workers in resource-based company towns. In short, a great deal more is known about the various political tendencies supported by workers and how conflicts between conservatives and radicals were central in shaping the path of the labour movements.

Much of this debate has developed around contrasting interpretations of the 1919 general strike wave and the One Big Unions with the early work of scholars like McNaught and Bercuson being rethought in numerous books, articles and theses. Commentaries such as The New Democracy (1991) by James Naylor and Larry Peterson's "Revolutionary Socialism and the Industrial Unrest in the Era of the Winnipeg General Strike" (Labour/Le Travail, 1984) sought to combine attention to local particularities with an eye on national trends and international politics. With the forthcoming volume on working-class activism during 1919, edited by Craig Heron, the debate is not likely to end soon.

Nor have disagreements within working-class history been confined to questions of culture and radicalism, as labour's relationship with the state has also been the subject of interpretive controversy. In broad terms, social-democratic historians have welcomed the creation of the reform-oriented welfare state and the enshrining of collective bargaining rights in law, while Marxists and others such as Bob Russell, in Back to Work? (1990), and Jeremy Webber, with "The Malaise of Compulsory Conciliation" (Character of Class Struggle, 1985) present a more critical view, emphasizing how industrial legality limited the potential of what unions could achieve by channelling struggles into an arena in which the related forces of governing and employing authority would always be more powerful than workers.

The latter group of scholars has analyzed coercive elements in Canadian state formation, piecing together the creation of the surveillance state during WWI and the use of the RCMP and deportation procedures to break strikes and expel socialists. Such methods were intensified during the Cold War purges of Communists from many industrial unions. Rarely the neutral arbiter of industrial relations, the Canadian government, at all levels, has tended historically to intervene in disputes in ways which reinforced the rights of capital, as with the complex, often ironic, impact of minimum wage laws, workers' compensation acts and other labour legislation. Also important are conflicts within the state; for example, as Gillian Creese observes in "Exclusion or Solidarity?" (BC Studies, 1988), the federal government's control over immigration policy was repeatedly challenged by provincial and municipal politicians and conservative white unionists eager to prevent the importation of workers seen as racially inferior such as Asians. These disputes contributed to the maintenance of a racially segmented labour force, as detailed by Alicia Muszynski in Cheap Wage Labour (1996).

The most productive area of new research has been that of labour's gendered past, as many of the central concerns of working-class history, whether new or old, have been revisited in light of feminist scholarship challenging the male-centred framework of writing about the Canadian past. The experiences of women working in the needle trades and clerical positions, for telephone companies and auto makers, have all shed light on the historically shifting composition of the sexual division of labour as well as struggles against the sexism of male bosses and unionists. Rather than a natural phenomenon, women's place in the occupational structure has been analysed as the product of conflicts over gendered notions of proper behaviour for women and men. In particular, the family wage - the idea that husbands were the legitimate breadwinner while wives were to be supported while doing the domestic labour - placed strong constraints on women's ability to find well-paying jobs. Nor were women working for "pin money"; instead, most entered wage labour in a context of economic need, trying to support themselves and their families in spite of the family wage ideal.

In a similar vein, the activities of women radicals have been unearthed by Linda Kealey, "No Special Protection - No Sympathy" (Class, Community and the Labour Movement, 1989), and Janice Newton, The Feminist Challenge to the Canadian Left (1995), for socialists in the period leading up to the 1919 labour revolt, and Joan Sangster, in a comparative study of women in the Communist Party and the CCF entitled Dreams of Equality (1989), all of which trace the often conflictual relationship between feminism and socialism. Moving beyond the world of work, scholarship by Bettina Bradbury entitled Working Families (1993) has revealed the importance of the family as both a resource in labour disputes and a site of antagonism around issues of economic responsibilities and entitlements.

Historians such as Steven Maynard and Mark Rosenfeld have focused attention on the gender identities of working men, revealing how class divisions and notions of solidarity and skill were often mapped in terms of popular understandings about masculinity. Joy Parr's The Gender of Breadwinners (1990), a study of working men and women in two small Ontario towns, is notable for its attempt to synthesize many of these historiographical trends, particularly in her exploration of the importance of both male and female gender identities for their experience at work and in the home.

In closing, it is worth noting that in Carl Berger's edited collection, Contemporary Approaches to Canadian History (1987), working-class history is the only area of inquiry where the editor felt obliged to present two conflicting assessments of the historiography, one representative of an older, institutional-oriented approach and another indicative of newer efforts to root the history of Canadian workers in broader processes of class formation. In 1996, BC Studies published a critical essay by Mark Leier with responses from Robert McDonald, Bryan Palmer and Veronica Strong-Boag, which resulted in a thought-provoking exchange on the direction of working-class studies, an issue explored in the overview presented in the second edition of Palmer's Working-Class Experience (1992). From its beginnings the history of Canadian labour has been contested terrain. It remains so to this day.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom