The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was the largest non-denominational women’s organization in 19th century Canada. Believing that alcohol abuse was the cause of unemployment, disease, sex work, poverty, violence against women and children, and immorality, the WCTU campaigned for the legal prohibition of all alcoholic beverages. Its membership was drawn from Canada’s growing middle class, and its members held evangelical Protestant views. The WCTU also advocated for women’s suffrage in Canada as a way to effect legislative change towards prohibition. The WCTU promoted the work ethic of sobriety, thrift, duty and family sanctity, and undertook community work such as reading rooms, homes for women and children, and prison reform.

Creation

The inspiration for the Canadian WCTU initially came from the United States. Beginning in the 1850s, groups of women tried to shame men into avoiding bars by standing and praying outside of, and sometimes in, barrooms in Ohio. In the summer of 1874, the American National WCTU was formed at an international Sunday school conference in Chautauqua, New York — the organization was officially founded that November in Cleveland, Ohio.

Although the first WCTU was formed in the United States, local temperance organizations had existed in Canada as early as the 1820s. A “Prohibition Women’s League” was formed in Owen Sound, Ontario, in May 1874 by Mrs. William Doyle, whose aim was to revoke the liquor licenses of grocery stores because of alcohol’s threat to family life. This organization is now recognized as the first Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in Canada.

Canada’s second WCTU branch was founded in Picton, Ontario, by Sunday school teacher and stepmother of eight, Letitia Youmans. Youmans had attended the Chautauqua, NY, Sunday school conference and returned to Canada inspired. (See also Early Women’s Movements in Canada: 1867–1960.)

Growth and Organization

Letitia Youmans played an important role in the WCTU’s spread throughout Canada. In 1875, she helped establish a WCTU branch in Toronto, and in 1877, became the first president of the newly created Ontario Provincial Union, which was made up of local branches of the WCTU. Youmans visited Western Canada in 1886 and organized local branches in Morley, Calgary, and Regina, in present-day Alberta and Saskatchewan. Unions were also established in Eastern Canada in Moncton (1875), as well as in Fredericton and Saint John, New Brunswick (both established in 1877). Branches continued to appear across Canada into the 20th century, with 578 unions reported in 1917.

Local WCTUs usually had an executive and a series of work departments headed by a superintendent. Once per year, local union presidents and superintendents met with the provincial executive at a convention where reports were submitted and resolutions debated. Although these local unions reported to provincial organizations, they retained a great deal of autonomy and shaped their activities according to local concerns.

Provincial executives reported to the Dominion WCTU, an organization created in 1883 by representatives from the Ontario and Québec WCTUs. The Dominion WCTU’s primary function was to speak on national issues and hold conventions; it was the first (technically) non-denominational woman’s group to organize at a national level in Canada. Youmans was the first president of the national organization — she had resigned as president of the Ontario WCTU in 1882 in order to found the Dominion WCTU. By 1900, the Dominion WCTU reported a membership of over 10,000 people, mostly women, with some honorary male members and auxiliaries.

The Dominion WCTU reported to the secretariat of the World WCTU, which was founded in 1885. The World WCTU tended to be dominated by the national WCTUs of the United States and Great Britain, but Canadian representatives also attended the world conventions.Indeed, following a dispute over organizational issues between the Québec and Ontario WCTUs in 1913–14, both organizations had better relations with the World WCTU than with each other.

Membership

The end of the 19th century was a period of uncertainty for many Canadians as industrialization, immigration, urbanization and other social change triggered concern about the survival of the ideal family. This period also saw the formation of a middle class in Canada, one that embraced the ideals of work, thrift, duty, sobriety and the sanctity of family life.The WCTU’s membership was largely drawn from the new middle class, as these women had the time and conviction to participate. Women involved at the local level, although still middle class, were often less affluent and had lower social standing than those at the provincial or national levels.

Members of the WCTU often held evangelical Protestant beliefs and aimed to reform society around the idea of a re-constituted Christian family (see Evangelical and Fundamentalist Movements). Members were concerned about the spiritual welfare of those they were trying to help, and believed that faith was the cornerstone of temperance (see Temperance Movement).

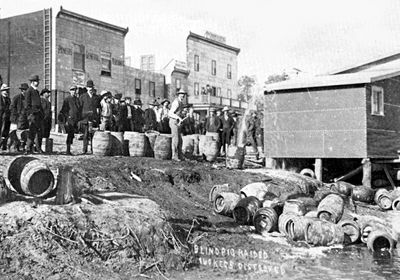

Prohibition in Canada

Members of the WCTU blamed alcohol for many of society’s problems and saw it as the biggest single cause of domestic violence and divorce (see also Family Violence). Members believed that drink was ruining Canadians’ physical health and linked alcohol to crime, sexual immorality and poverty. They believed that women and children were innocent victims of alcohol’s effects, as men’s abuse of alcohol invaded the home and led to violence towards women and children.

Early temperance movements had thought that individual effort, rather than legislative change, was the best route to redemption from alcohol. The WCTU had initially campaigned for temperance using petitions, by creating and circulating literature, and through speeches. However, by the 1880s, Letitia Youmans and the Ontario WCTU were convinced that temperance could only be achieved through legislative change.

The early petitions enjoyed some limited success, as governments were made aware of the demand for prohibition. Several provinces held plebiscites (referendum votes) on the issue, followed by a national prohibition plebiscite in 1898. The majority of voters were in favour of prohibition, but cities, immigrant communities and the province of Québec voted against it. Facing such divisions, the government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier did not act.

Although the federal government controlled the making and trading of alcohol, provinces could regulate the sale of liquor. The first province to enact prohibition was Prince Edward Island in 1901, and during the First World War all provinces except Québec voted “dry,” mostly as a patriotic sacrifice to win the war. In 1918, the federal government stopped the manufacture and importation of liquor into “dry” provinces. These regulations were a high point for the WCTU.

Women’s Suffrage in Canada

In the WCTU’s early years, the organization had not supported women’s right to vote. However, through its increasing focus on temperance through legislative change, temperance and women’s suffrage became mutually supportive issues. The WCTU provided a platform for women to be publically active participants in their communities, and the organization insisted that its members had a right to participate in public life. In 1888, the Dominion WCTU Convention endorsed women’s suffrage, making it the first major national organization to do so in Canada.

Women had asked to be able to vote in the 1898 national plebiscite on prohibition and had been refused. The government’s inaction after the plebiscite convinced many that it was not acting in the best interests of the people. Members of the WCTU became increasingly frustrated by having to rely on men to create the kind of society they wanted to live in. Despite these frustrations, the WCTU continued to advocate for women’s suffrage as a way to positively shape society.

(See also Mock Parliament, 1914.)

Community Work

Although prohibition was the WCTU’s main focus, its members were involved in other aspects of social reform.Local chapters responded to needs within their own communities, such as free libraries and reading rooms in the Westmount neighbourhood of Montréal. The Ontario WCTU and others also organized youth groups such as the Little White Ribboners and the Young Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. There was a range of activities across the country, but many focused on providing assistance to unwed mothers, sex education, anti-smoking, social purity and prison reform. Other initiatives included childhood and adult education, homes for “fallen” women and orphaned children, women’s hospitals, and residences for single working women. It should be noted, however, that these philanthropic works were generally confined to women who shared the same religion and ethnicity as the WCTU members, who were both Christian and White.

Legacy

When prohibition ended in the 1920s, the WCTU found that it had grown out of touch with society. The passage of laws implementing provincial systems for the control and sale of alcohol across the country reduced the WCTU’s influence with the general population. In the 1920s, many members, notably in Saskatchewan, became polarized over the single-minded attachment to prohibition, which led moderates to leave and those remaining to become increasingly conservative and moralistic.

The WCTU continued to perform its community work and remained active in the temperance movement, although they had few successes. By the 1960s, despite its focus on drug use, the organization seemed oriented towards an older kind of moral reform that did not resonate with the wider society.

Additionally, the professionalization of social work meant that the role of untrained middle-class women in community work was diminished. Medical and social science research also encroached on the WCTU’s analysis of the societal effects of alcohol consumption, further eroding the organization’s relevance.

Today, the Canadian Woman’s Christian Temperance Union’s membership numbers are reduced, but it continues to be a member of the World Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. It focuses on educating Canadian society about the dangers of alcohol, tobacco and other non-prescription drugs. In 1995, there were 1,700 members in 67 branches, as compared to 2,473 in 1987.

See also Temperance Movement.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom