Background: First Nations, France and War

The area that became Upper Canada was populated originally by First Nations people, in particular the Wendat, Neutral, Tionontati (Petun) and Algonquin, among others. (See also First Nations in Ontario.) Samuel de Champlain visited the region in the early 17th century. He claimed the territory for France and was followed by other French explorers. Missionaries were particularly active in Huronia, east and south of Georgian Bay. (See also Sainte-Marie among the Hurons.) Through the fur trade, the French firmly established themselves in the area by the 18th century. Modern Toronto, Windsor, Niagara and Kingston were established.

During the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), the French abandoned most of the region to the British. Upon the surrender of Montreal in September 1760, Britain effectively took over the territory that would later become Upper Canada. After the Treaty of Paris (1763) and the Royal Proclamation later that year, the borders of Britain’s new Province of Quebec were expanding.

With the Quebec Act of 1774, the borders moved west into what is now southern Ontario, north to include all of Labrador, and south into the Ohio Valley. When the American Revolution began in 1775, the permanent European population of western Quebec consisted mainly of French-speaking settlers around Detroit. By the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783, what had been a trickle of wartime Loyalist refugees into the area became a stream. About 7,500 refugees established a British-centered ideology that would influence much of Upper Canada’s future. (See also Black Loyalists in British North America.)

Settlement by Loyalists

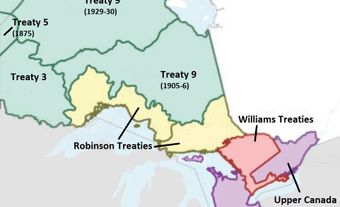

Land settled by Loyalists and other European settlers was the traditional territory of Indigenous peoples. The Upper Canada Land Surrenders ceded Indigenous lands to the colonial government for the purposes of settlement and development. These treaties cover much of what is now southwestern Ontario. By the mid-1830s, treaties covered most of the arable lands in Upper Canada. By the time of Confederation in 1867, nearly all of Ontario was covered by a treaty. (See also Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Governor Sir Frederick Haldimand began Loyalist settlement initiatives. He established militia units in range of quickly-surveyed townships along the American border. In the event of war, these veterans were intended to form a defensive barrier. Three main areas were selected: along the St. Lawrence River, around Kingston and the Bay of Quinte, and in the Niagara Peninsula. A fourth, near Detroit, was considered, but its scheduled surrender to the US postponed development.

Land was granted in lots, with heads of families receiving 100 acres, additional family members getting another 50 acres, and field officers receiving up to (and eventually more than) 1,000 acres. Clothing, tools and provisions were supplied for three years. Such conditions favoured the Loyalist migrants, many of whom did well. Many disgruntled Americans, some simply “land-hungry,” eventually moved north to join them. By 1790, western Quebec had a population of about 10,000 settlers.

The Loyalists who came to Upper Canada, mostly American frontiersmen, were well able to cope with the rigours of new settlements. In addition, they were not politically docile. Many had been in the forefront of political protest in the old American colonies. Although they had not been ready to take up arms for colonial rights, they were prepared to use every legal and constitutional means at their disposal to better their lives. Their main concerns included a push for more representative government, as well as laws and institutions that reflected their British heritage, not those of France. It was their constitutional complaints that caused Britain in 1791 to modify the inadequate Quebec Act of 1774.

New Colony Created

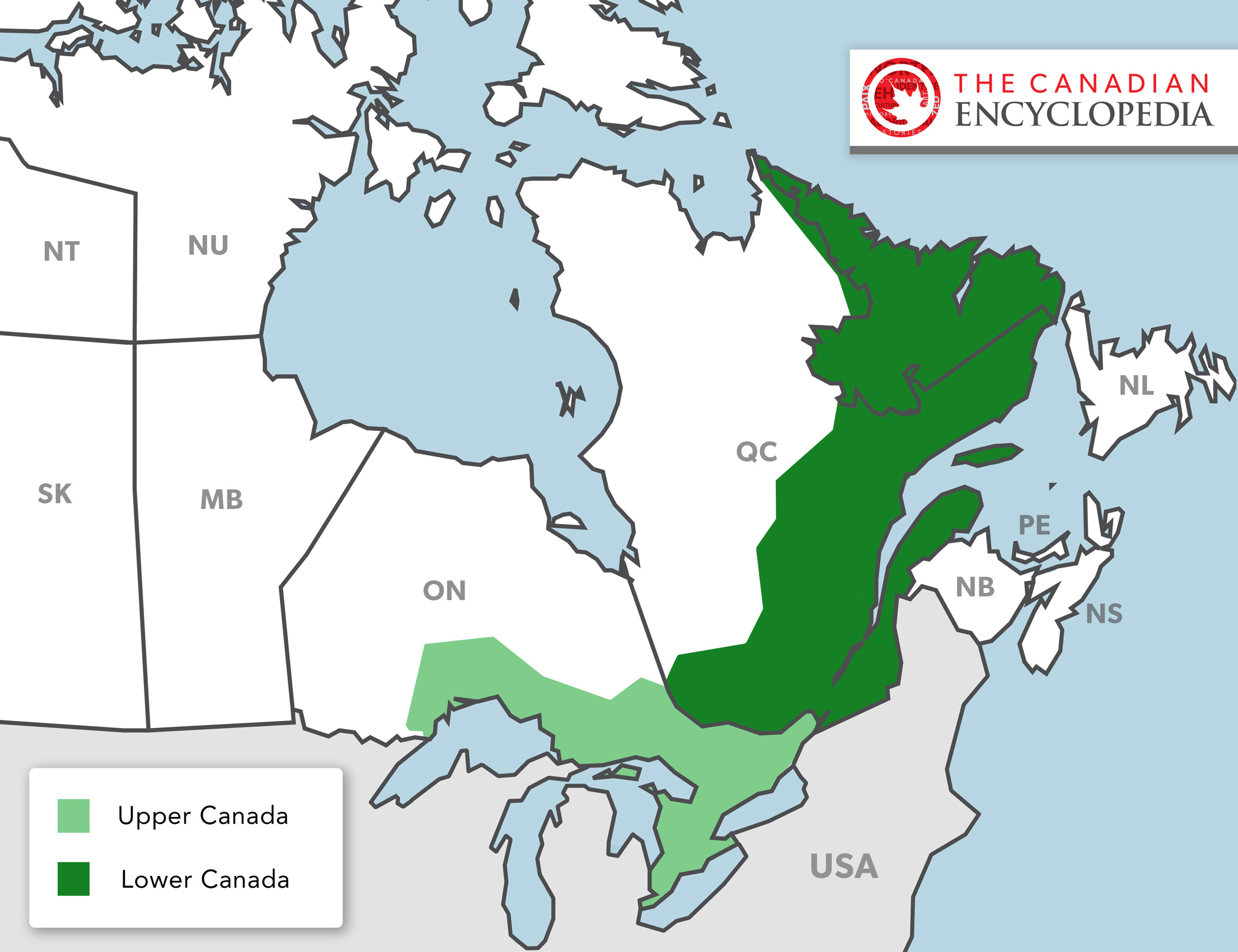

The result was the Constitutional Act, 1791. The Act divided the Province of Quebec into Lower Canada to the east (on the lower reaches of the St. Lawrence River) and Upper Canada (along the lower portion of the present-day Ontario-Quebec boundary) to the west. The Act also established a government that would largely determine the colony’s political nature. It also strongly influenced the territory’s social and economic character.

The Constitutional Act was, in large part, a clear response by the British to the American Revolution. As the British government saw it, the excess of democracy that had permeated the American colonies would not be allowed in the two new provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. A lieutenant -governor was established in each province, with an executive council to advise him, a legislative council to act as an upper house, and a representative assembly. Policy was to be directed by the executive, which answered not to the elected assembly but to the Crown.

It was hoped that the Church of England would tie the colonies more firmly to Britain. In Upper Canada, a permanent appropriation of funds “for the Support and Maintenance of a Protestant clergy” was formally guaranteed by the establishment of one-seventh of all lands in the province as clergy reserves. The proceeds from their sale or rental went to the church. Subsequent instructions established crown reserves on another seventh of the land. The revenue from these were used to pay the costs of the provincial administration.

Land ownership, the question that concerned most settlers, was to be on the British pattern of freehold tenure. The seigneurial system common in Lower Canada was permanently eradicated in the upper province. Meanwhile, the voting franchise was fairly wide. The assembly in Upper Canada numbered no fewer than 16 members while the Legislative Council was made up of at least seven.

First Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe Takes Charge

The first leader of this new wilderness society was Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe. His stated purpose was to create in Upper Canada a “superior, more happy, and more polished form of government.” He wanted not only to attract immigrants, but also to renew the empire and set an example that would win Americans back into the British camp. Governmental institutions were established, first at Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) and then at the new capital at York (now Toronto). Simcoe used troops to build a series of primary roads, got the land boards and land distribution under way, established the judiciary, made inroads in abolishing slavery in 1793 (An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude Statutes of Upper Canada) and showed a keen interest in promoting Anglican affairs.

When he left the province in 1796, due to illness, Simcoe could take pride in his achievements, even though he had failed to convert Americans from republicanism or to persuade Britain to turn Upper Canada into a military centre. To Britain, Canada still meant Quebec, and Simcoe’s elaborate plans for the defence of a western frontier beyond the sea-lanes were unrealistic.

Upper Canada did not flourish under those who succeeded Simcoe as lieutenant-governor. In the years between his departure and the War of 1812, the province largely remained a remote frontier of fragmented but growing settlement. And land, the only real source of prosperity, had too often been carelessly carved up in huge grants by lax administrators.

Family Compact Takes Control

Politics began to emerge in provincial life. The Constitutional Act, 1791, by its very nature, had created a party of favourites. Lieutenant-governors chose their executive and legislative councils from among men they could trust and understand, who shared their solid, conservative values: namely, Loyalists or newly arrived Britons. These men — later called the Family Compact — quickly became a kind of Tory club, or faction permanently in power. They could not conceive any brand of loyalty to the Crown apart from their own. When opposition arose, as it did frequently over budget matters, those advocating an extension of the legislative assembly’s powers gathered support. However, they were met by serious opposition from the Compact, who sometimes threatened or brought charges of sedition. But the influence of sincere political critics such as Robert Thorpe, Joseph Willcocks and William Weekes was to be washed away by the War of 1812.

War of 1812

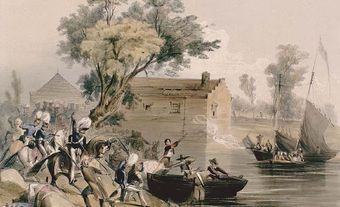

During the War of 1812, Upper Canada, whose inhabitants were predominantly American in origin, was invaded a number of times and partly occupied. American forces were repulsed by British regulars assisted by Canadian militia and Indigenous groups. (See also First Nations and Métis Peoples in the War of 1812.) The war strengthened the British link, rendered loyalism a hallowed creed, fashioned martyr-heroes such as Sir Isaac Brock and Tecumseh, and appeared to legitimize the political status quo.

The war ended Upper Canada’s isolation. American immigration was formally halted, but Upper Canada received an increased number of British newcomers, some with capital to spend. The economy continued to be tied to Britain’s colonial trade policies and mercantilism. The wheat trade became most important to Upper Canadian farmers. Still, the war had been very costly, and the province remained capital poor. For example, the Welland Canal Co., a public works venture, had to look abroad for investors. (See also Welland Canal.)

Economic Turmoil

The expense of administering the growing colony increased substantially in the early 1820s, and schemes to reunite the two Canadas were occasionally considered. In 1822, an effort was made to adjust the customs duties shared with Lower Canada to provide the upper province, which had no ocean port, with a larger share of revenue. In practice, this effort proved largely unsuccessful.

Revenues remained inadequate and the province was plunged into debt. It was unable to pay the interest on its own badly received bonds without further borrowings. The establishment of the Bank of Upper Canada (1821) and other banks failed to bring real fiscal stability. The contributions of the massive British-based colonization venture, the Canada Company, also fell short. In fact, Canada Company payments were used to defray the salaries of government officials (the civil list), thus averting the assembly’s desire to control government revenues.

The War of 1812 allowed the Family Compact, led by Anglican Archdeacon John Strachan (later bishop of Toronto), to consolidate its political control, often in ways that were corrupt. There is evidence of patronage appointments to official positions and to emerging banks, and the preferential granting of land. The group was rigorous and methodical in its administration, though not always so sound in its financial management. It did have a strong sense of duty toward development, as shown by its unswerving support of public works such as the Welland Canal. But an oligarchy increasingly proved to be an anachronism in an age that was tilting towards democracy.

Rebellion in 1837

By 1820, opposition in the province was becoming sophisticated, but its politics were not yet dominated by disciplined parties. Some agitators, such as the “Banished Briton” Robert Gourlay, had dramatized popular grievances in martyr-like fashion. Until the mid-1830s, opposition was usually led by more moderate politicians such as Dr. William Baldwin, Robert Baldwin and Reverend Egerton Ryerson.

Reformer William Lyon Mackenzie wanted Upper Canada to be a US-style republican democracy. He desired a province composed of firmly patriotic farmers, ready to become British-American revolutionaries. Mackenzie’s Rebellion of 1837 sought to seize power from the Family Compact and its supporters in the church. It failed because, like so many politicians after him, Mackenzie failed to understand the basic, moderate political attitudes of Upper Canadians.

Mackenzie’s violent posturing and his poorly supported rebellion turned out to be unnecessary. Gradual democratic reforms were already underway in both the colony and Britain. The inadequacies of the Constitutional Act, 1791, with its rigid colonial structures, were by now apparent. For Upper Canada, real political change could only come from England, although it could be accelerated by advocates in the province.

Some immediate change came through the efforts of the Earl of Durham in 1838. As governor general of British North America, he spent only a few days in Upper Canada. But he found time for a short, formal visit to Toronto and an interview with Robert Baldwin. He also received sound counsel from his advisers, especially Charles Buller, all of which he included in his famous report. (See Durham Report.)

Union with Lower Canada

Durham’s report and its recommendations set in motion a scheme that had long been considered: the reunification of Upper and Lower Canada. By 1838, Upper Canada had a diverse population of more than 400,000 people. It stretched west from the Ottawa River to the head of the Great Lakes. It was still a rough-hewn and somewhat amorphous community, poorly equipped in terms of schools, hospitals or local government. From his lofty imperial perch, Durham suggested that a reunion of the provinces would swamp the French of Lower Canada in an English sea. More importantly, the economic potential of both colonies would be enhanced, thereby making them less burdensome to Britain.

Durham insisted that these outcomes would easily be advanced under responsible government. The Cabinet, or executive council as it was called then, would be made responsible and accountable to the elected assembly rather than to the Crown and the lieutenant governor. The errors of the Constitutional Act, 1791 could be exorcised and unruly politics subdued without fear of further revolts. Britain approved the union, although the actual granting of responsible government would take almost a decade more.

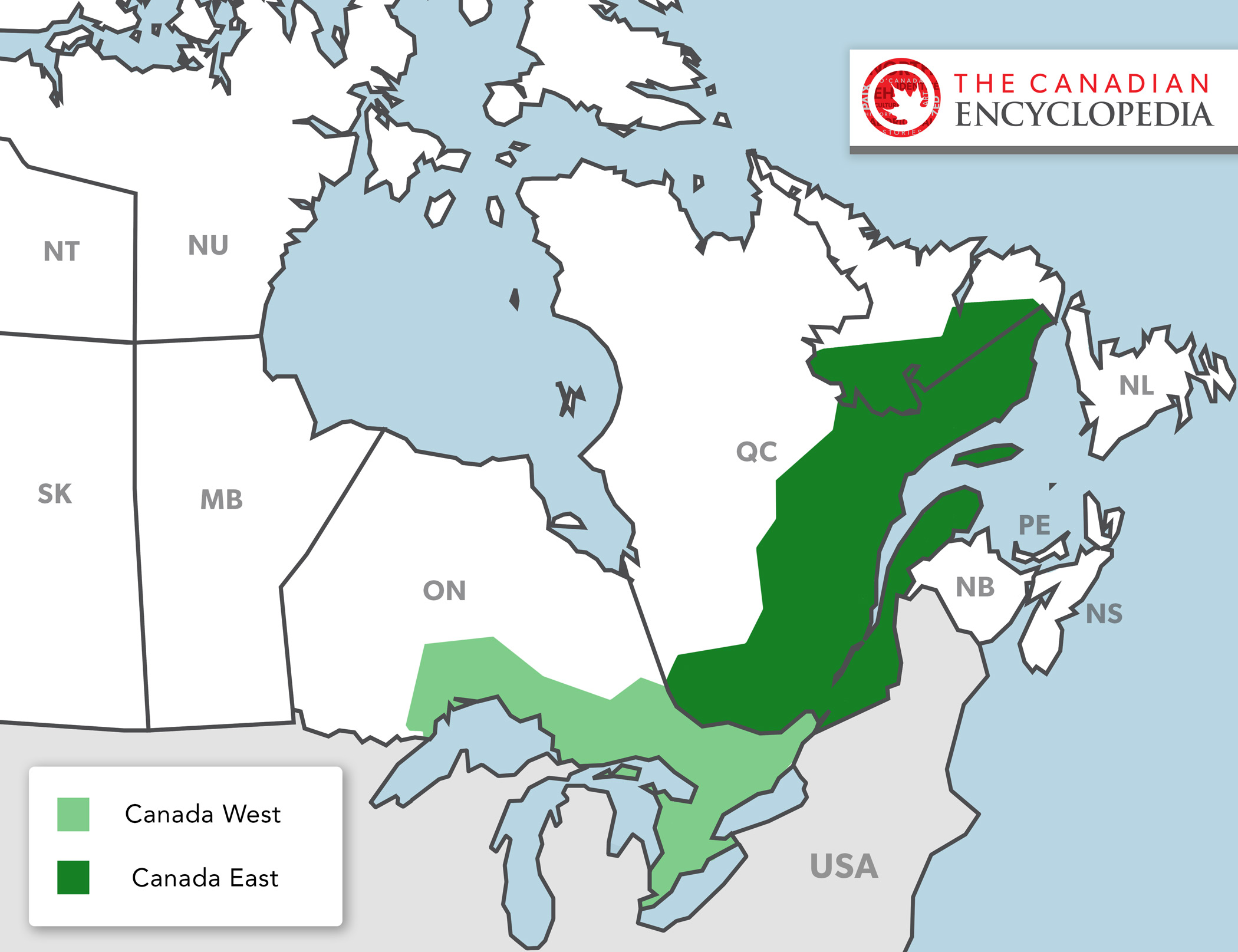

On 10 February 1841, Upper Canada’s history came to an end. The colony united with the largely French-speaking Lower Canada to form the new Province of Canada. ( See also Act of Union.) Despite their tumultuous history, Upper Canadians could make some claim to having a collective past. With the prospects of a rapidly increasing population, greater democracy and improving agricultural opportunities, they could look forward to a brighter, collective future.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom