Early Years and Education

Tom Thomson came from Scottish Canadian stock. The sixth of ten children, he was born in the town of Claremont in Pickering Township, Ontario. He grew up on a farm near Leith, outside Owen Sound. His father, a farmer, was something of a naturalist; one of his older cousins, Dr. William Brodie, was one of the finest naturalists of the day (he served as director of the Biological Department of what is now the Royal Ontario Museum from 1903 to 1909). Tom Thomson collected specimens with Dr. Brodie, who gave him informal training as a naturalist. From Brodie, Thomson learned how to combine keen observation of nature with a sense of reverence for its mystery.

Brought up in a creative family, Thomson learned to play several musical instruments, among them the mandolin. He sang in the church choir and learned to draw and paint. After missing a year of high school as a result of chronic illness, he worked at a foundry and a machine shop in Owen Sound. He then enrolled in the Canada Business College in Chatham (he is listed in the city directory in 1902). Later in 1902, he attended the Acme Business College in Seattle, a school run by his eldest brother George and a cousin, F.R. McLaren.

Early Career

In Seattle, Thomson got his first job with a commercial art company. (See Graphic Art and Design.) He worked as an engraver and calligrapher with a firm run by C.C. Maring, one of the graduates of the Chatham Business College. He worked briefly for Maring & Ladd, which became Maring & Blake soon after he arrived due to a change in ownership. He was then hired by their strongest competitor, the Seattle Engraving Company, at an increase of $10 a week. His work included creating business cards, brochures and posters.

Thomson doubtless looked forward to a career in Seattle. He probably wanted to settle down, advance in his trade and marry, as his brother Ralph did in 1906. That he did not was likely the result of an incident involving Alice Elinor Lambert, eight or nine years his junior, to whom he proposed. At the crucial moment, Miss Lambert nervously giggled, causing the highly sensitive Thomson to abandon his matrimonial ambitions and leave for Toronto. It was on his return from Seattle that he decided to become an artist. (Lambert, according to David Silcox, “went on to write romantic novels, one of which featured a young girl who was wooed by an artist and refused him, to her later regret.”)

Early Painting Career

In terms of his development as a painter, Thomson’s experience up to this point was primarily that of an amateur. In order to become a professional artist, he had to overcome numerous obstacles, such as his lack of knowledge of the technical side of painting. In 1906, he enrolled in night school at the Central Ontario School of Art and Industrial Design — the precursor to today’s Ontario College of Art and Design University.

Beginning around 1908, Thomson became involved with a lively group of comrades at Grip Limited, a well-known commercial art firm. When Thomson joined Grip, the company was at a crucial stage of its development. It had a good art director, A.H. Robson, and a painter, J.E.H. MacDonald, who was the anchor of the design team. Thomson worked with MacDonald, and it was under his tutelage and encouragement that Thomson’s genius began to blossom. He submitted his work at the firm to MacDonald and showed the sketches he painted on weekends to MacDonald and others at the firm. MacDonald and men such as Robson, a member of the Toronto Art Students’ League (see Artists’ Organizations), praised the truth to nature in Thomson’s work.

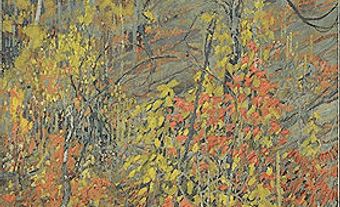

In 1912, Thomson embarked on a camping trip to the Mississagi Forest Reserve north of Lake Huron. Upon his return, he was told by his friends at Grip that his sketches made during this trip expressed a real sense of the character of the northern landscape. The next year he returned to Rous & Mann Limited (the firm to which Robson, and then all of Thomson’s colleagues from Grip, moved in 1912). He brought with him works that he had painted that year on a fishing trip to Algonquin Park. These sketches of 1912 showed a tremendous advance and marked his real start as an artist. They depict wilderness as a great world that seems unsullied by human civilization. They portray the natural world in a way that is poetic but still informed by direct experience.

Mature Painting Career

Thomson was an intense, wry and gentle artist with a canny sensibility. He was one of the first painters to give acute visual form to the Canadian landscape as he discovered it in Algonquin Provincial Park, which had been set aside as a conservation area in 1893.

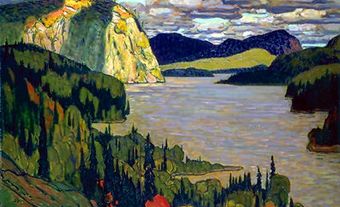

To develop his first major painting, Northern Lake (1913), Thomson selected one of the sketches from his trip to Algonquin Park and transformed it into a picture with greater depth in the foreground. (Northern Lake is now in the permanent collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario.) This method of working from an on-the-spot sketch to a finished studio painting became his common practice. These two ways of working reveal contrasting sides of Thomson’s artistic personality. The sketch, with its vivacity and on-the-spot reportage, recalls the spontaneity of a lyric poem. The canvas created in the studio, with effects adapted from such styles as art nouveau and post-impressionism, is akin to an epic poem.

In the autumn of 1914, Thomson and his friends A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer and Frederick Varley camped in Algonquin Park. By that time, Thomson was transposing, eliminating and applying various types of design to his work in order to evolve his conception of landscape painting. This would eventually become the basis for a style that would bring national prominence to the Group of Seven, a movement that infused a growing Canadian consciousness into the practice of landscape painting. Thomson had informally discussed his ideas about this new approach with J.E.H. MacDonald and Lawren Harris.

By 1915, Thomson was creating the oil paint sketches and canvases that have come to represent Canada as it is imagined by most Canadians. At 37 years of age, he was living in Algonquin Park from spring to autumn (at times serving as a fishing guide and a fire ranger), and in Toronto during the winter. He shared Studio One of the Studio Building in Toronto with A.Y. Jackson, and then, when Jackson left, with Franklin Carmichael. Thomson eventually moved to a shack attached to the building. Here he painted his large canvases and entertained friends such as his patron, ophthalmologist Dr. James MacCallum, and Lawren Harris.

Working Methods and Artistic Expression

An examination of Thomson’s works reveals how quickly he came into his own. An amateur artist, he found his very distinctive path by 1914. Nature was clearly his touchstone, and throughout his career he turned to it as his muse. His method was to capture transient moments of light and atmosphere by sketching quickly in oil from nature, sometimes developing these sketches into full-blown celebrations of the land. His evolution was toward a relaxed, brilliant handling of paint. At his best, Thomson disposed trees and bushes in his paintings like notes in a finely phrased tune, creating patterns that interlocked in intricate counterpoint.

He also saw connections between music and painting. He once told a friend that “Imperfect notes destroy the soul of music. So does imperfect colour destroy the soul of the canvas.” One can see in his design a correlation to musical intervals, contributing a sort of rhythm, touch and tone to his paintings. Most engaging for the viewer are his bold use of colour and his sense of spectacle channelled through an experience of northern nature. Although few people are shown in his works, the views that he painted suggest places where people can meditate in quiet.

Masterpieces like The West Wind and The Jack Pine present a similar motif of a tree or trees on a rocky shore that conveys a sense of iconic grandeur. Thomson’s pictures, with their rich colours, often have a sense of movement, of dynamism and drive. His best-looking paintings to contemporary viewers are his lively sketches with their strong forms. Executed in a palette of red, pink, brown, light and dark blue, with a finesse suited to a naturalist, Thomson’s paintings embody a truly national vision.

Death and Mythology

On 8 July 1917, Thomson embarked from Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park in a canoe loaded with equipment and supplies. His upturned canoe was found later that day and his body was found in the lake eight days later. He had a bruise on the right side of his head and had bled from his right ear. The cause of his death was ruled as “accidental drowning,” though the inquest that reached that conclusion was criticized as being rushed. A police investigation was never conducted.

Thomson’s body was interred at Mowat Cemetery near Canoe Lake the day after it was discovered. It was exhumed two days later and buried in the Thomson family plot in Leith on 21 July. In September 1917, James MacCallum, J.W. Beatty and J.E.H. MacDonald erected a stone cairn with a memorial plaque at Hayhurst Point, overlooking Canoe Lake.

The circumstances surrounding Thomson’s death have taken on a mythological life of their own. Writers, amateur sleuths and serious scholars have proposed various theories over the years. In a 1977 Toronto Star article, Roy MacGregor suggested that Thomson was murdered by Shannon Fraser, the owner of Mowat Lodge, and that his wife, Annie Fraser, told the story to friends. MacGregor expanded on this thesis in his 2010 book, Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him.

In all likelihood, Thomson’s death was an accident. As David Silcox has argued, “The simplest explanation is therefore likely the correct one — that Thomson stood up in his canoe, lost his balance, and fell. He hit his forehead on the gunwale in the process, knocked himself out, and slipped into the water, where he drowned — as the coroner’s report confirmed.” However, many have found this conclusion difficult to reconcile with Thomson’s reputation as a skilled canoeist and outdoorsman. The exact circumstances of his death may never be known.

Tributes and Influence

Arthur Lismer described The West Wind as “the spirit of Canada made manifest in a picture.” He also wrote that “Thomson was a sort of Whitman: a more rugged Thoreau if you will, but he did the same things, sought the wilderness, never seeking to tame it but only to draw from it its magic of tangle and season, its changing skyline and its quiet or vigorous moods.”

In 1927, A.Y. Jackson called Thomson “our ideal of an artist. The more you think of Tom Thomson the greater the man becomes.” Lismer also wrote that “what he saw and did set the stage for what we know about Canada, satisfying the curiosity about the remote and vast hinterland of the North. If art…is a part of the national establishment then Thomson’s contribution was unique and stimulating.”

Acclaimed painter and art critic David Milne once wrote of Thomson’s significance within Canadian culture, “I rather think it would have been wiser to have taken your ten most prominent Canadians and sunk them in Canoe Lake — and saved Tom Thomson.”

Tom Thomson's memorial cairn near Hayhurst Point overlooking Canoe Lake. The stone work was by J. W. Beatty. J. E. H. MacDonald designed the bronze plate.

Collections

Thomson left behind about 50 canvases and more than 400 sketches. In 1918, the National Gallery of Canada bought The Jack Pine, Autumn’s Garland and 27 of Thomson’s sketches from his patron, Dr. James MacCallum. MacCallum donated the rest of his collection to the gallery in 1943. The Jack Pine was exhibited at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley (London, England), where it received rave reviews.

Two dozen galleries across Canada house collections of Thomson’s works. The largest is held at the National Gallery. Others include the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound (established in 1967), the Art Gallery of Ontario, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom