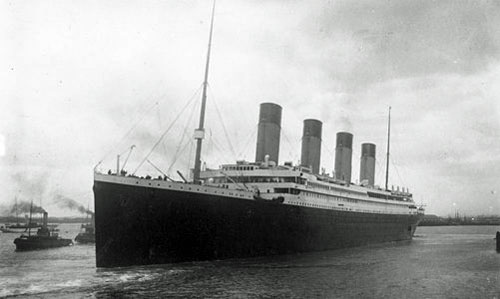

The Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Titanic was a British luxury passenger liner that sank on its maiden transatlantic voyage. At approximately 11:40 p.m. on 14 April, 1912, about 740 km south of Newfoundland, Titanic’s starboard (right) side scraped along an iceberg. The collision ruptured several watertight compartments. Water poured in, but the first lifeboat was not launched until an hour later. Approximately two-thirds of the liner’s passengers and crew died. Titanic’s sinking was one of the worst marine disasters in history and remains firmly embedded in popular culture today.

Concept and Construction

In 1907, J. Bruce Ismay, the managing director of the White Star Line, and Lord Pirrie, chairman of the Belfast shipyard Harland and Wolff, decided to build a larger and more luxurious class of ships to compete with their rival, the Cunard Line. Their ideas led to the Olympic class of three ships: Olympic, Titanic and Gigantic (later renamed Britannic). The ships were built to carry a mix of first- and second-class passengers in unrivalled luxury; even third-class facilities exceeded those of other lines.

Construction of Titanic began on 31 March 1909 in Belfast. Approximately 3,000 workmen were involved, eight of whom were killed during construction. The men worked an average of 49 hours over a six-day week, for which they were paid ₤2 (about $413 in 2022). Titanic was launched 26 months later, on 31 May 1911.

Although launched, Titanic was simply an empty hull, and “fitting out” followed over the next few months. This included installing propulsion machinery and completing the accommodations and common areas. In total, Titanic cost ₤1.5 million to build (approximately $309 million in 2022).

Titanic completed its sea trials in the Irish Sea on 2 April 1912 and received its seaworthiness certificate from a senior representative of the Board of Trade. The ship then headed for Southampton, 1,060 km away, to begin its first — and last — passenger voyage.

Titanic Sails

After Titanic arrived at Southampton, it spent six days taking on additional crew members (including Captain Edward Smith), coal and provisions. On 10 April, 951 passengers boarded the ship, which then sailed for Cherbourg, France, to pick up more passengers. Titanic then departed for Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, where it arrived at 11:30 a.m. on 12 April.

Two hours later, Titanic sailed for New York. According to best estimates, the ship now carried 1,316 passengers: 325 first class, 285 second class and 706 third class. The crew of 913 brought the total number of people aboard Titanic to 2,229. Fortunately, the ship was not full; if it had been, it would have resulted in even greater loss of life.

Among the first-class passengers were some of the world’s wealthiest people. The richest person aboard was John Jacob Astor IV, accompanied by his much younger second (and pregnant) wife, Madeleine. Other millionaires included Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor and Ida Straus (owners of Macy’s in New York) and members of several other wealthy American families.

Several passengers had a Canadian connection. Some had been born there; Harry Markland Molson, for example, was a member of the famed Montreal brewing, banking and shipbuilding family and the richest Canadian aboard. (See John Molson and Molson Coors Beverage Company.) Others, like American railway tycoon Charles Melville Hays, lived and/or worked in Canada. A few were going to Canada temporarily for business or family reasons, while others were immigrating to Canada. In total, 130 passengers were bound for Canada, representing all three classes; only 82 survived.

Disaster

At 11:40 p.m. on 14 April, three days after departing Queenston, Titanic struck an iceberg. Captain Smith had received six warnings from other ships about icebergs in the area but seemingly chose to ignore them. When Titanic collided with the iceberg, the ship was travelling at 0.5 knots below its top speed.

Titanic had been constructed with 16 supposedly watertight compartments, but they were not truly watertight. The bulkheads dividing the compartments did not reach completely to the deck above but had a gap at the top. If a compartment filled with water, it could then spill over and flood the next one.

The iceberg ruptured five or six compartments, and water poured in through several gashes. Titanic could have stayed afloat if only four compartments had been flooded, but five or six doomed the ship. As each forward compartment filled, water flowed over the top of the bulkhead, much like water in a tilted ice cube tray. Very slowly, Titanic began to go down by the bow.

At first, most passengers were unaware of the collision, while those who knew about it were unconcerned. After all, they were on the largest and perhaps the safest ship in the world. Some had even called it “unsinkable.” The iceberg was treated as an object of curiosity.

Lifeboats

Titanic carried 20 lifeboats: 14 wooden ones (which could carry 65 persons each), four collapsible ones with canvas sides (47 each) and two wooden emergency cutters (40 each). They could carry 1,178 people in total, which was only one-third the ship’s maximum capacity. This was legal at the time because lifeboat numbers were based on the gross registered tonnage of a ship and not the number of people aboard it.

Captain Smith ordered a distress call sent out at 12:15 a.m. on 15 April but did not direct lifeboats to be loaded until 12:35. Lifeboat 7, the first one launched, entered the water at 12:40. It carried only 28 people, far fewer than it could hold. A similar story was repeated as other lifeboats were launched; none were filled, although some of the latter ones were almost fully occupied. The last two lifeboats were launched at 2:15, only five minutes before Titanic went down.

If all of Titanic’s lifeboats had been filled, another 472 lives would have been saved, including all women and children and almost 650 men. But many men and older boys were denied entry to partially filled lifeboats by one of the ship’s officers who interpreted the order “women and children first” as “women and children only.”

Did you know?

The tradition of allowing women and children to leave a sinking ship before men began in the 19th century and became widely known following the sinking of HMS Birkenhead on 26 February 1852. The British troopship was carrying 634 soldiers and a few officers’ families when it hit an uncharted rock off the South African coast. Water poured in through a huge rip in the hull, quickly drowning several soldiers. Survivors gathered on the deck, only to discover that only three lifeboats were seaworthy. As the men stood back, women and children boarded the lifeboats. Birkenhead broke up and sank 25 minutes after hitting the rock. Only 193 survived, including all the women and children.

Rescue and Recovery

The RMS Carpathia, a passenger ship from White Star Lines’ rival, Cunard, was on its way from New York to Mediterranean ports when its wireless operator heard Titanic’s distress call. Captain Arthur Rostron immediately changed course and proceed to the sinking ship’s location. He arrived in the area about four hours later. Titanic’s lifeboats were scattered over a wide area, and it took Rostron another four and a half hours to pick up the 713 passengers and crew who had survived, only one-third of all those aboard Titanic. He then turned Carpathia around and headed back to New York. On arrival on 18 April, Carpathia was met by huge crowds. Survivors were taken to hospitals and other facilities according to their needs.

Relatives, newspapers and members of the public soon demanded that White Star Line recover the bodies of victims. The company contracted four Canadian ships for the purpose. In total, the ships recovered 328 bodies, of which the Halifax-based cable ship Mackay-Bennett retrieved 306. Of the 328 victims, 119 were buried at sea for various reasons and 209 taken to Halifax. Relatives requested 59 bodies be sent to their home locations for burial, while the remaining 150 were buried in three Halifax cemeteries. Another nine bodies were buried at sea by passing ships.

Aftermath

Both the Americans and the British conducted inquiries, resulting in several changes to transatlantic passenger ship travel. Ships now had to carry enough lifeboats for all onboard, stocked with survival equipment and manned by trained crews. Everyone onboard had to participate in a lifeboat drill. All passenger ships had to have wireless communications, which were to be manned full time. Ships’ messages were to take priority over private ones. Ships were now required to go around icefields rather than through them. The International Ice Patrol was also established to warn ships of icebergs.

Discovery of the Wreck

A joint Franco-American expedition located the wreck of Titanic on 1 September 1985 using a camera-equipped submersible. Titanic was in two large upright sections 600 metres apart, at a depth of 3,840 metres, some 24 km southeast of its last reported location. Further dives by others recovered several thousand artifacts. Visits by other deep-ocean submersibles have since taken place, including ones carrying tourists. Eventually nothing will be left of Titanic as the materials that make up the ship continue to deteriorate.

Titanic in Modern Memory

Public fascination with the Titanic tragedy has made it the subject of several films, books, exhibits and other forms of education and entertainment. Several novels, including one from the viewpoint of the iceberg by Canadian oceanographer-ornithologist R.G.B. Brown, and the musical The Unsinkable Molly Brown, were inspired by the tragedy, as was E.J. Pratt's long narrative poem, “The Titanic.” There have been several documentaries, exhibits, songs and movies made of the event, including James Cameron's Titanic, a blockbuster hit in 1997. Cameron resurrected his hit movie in 3-D in 2012, in time for the centennial of the ship's sinking. Canada Post also published a series of stamps to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the tragedy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom