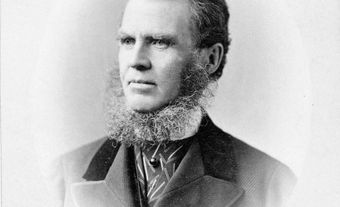

Early Life in Ireland

Thomas D’Arcy McGee was born in a small coastal village in eastern Ireland. His background was by no means privileged. His mother loved Celtic mythology and sympathized with the national struggle against the British. Thomas became versed in Irish culture from a young age.

Career in the United States

In 1842, at age 17, he emigrated from Ireland to the United States. He eventually settled in Boston and began to make a name for himself almost immediately. He delivered a speech criticizing British rule at the society of the Boston Friends of Ireland. He was then hired at the Boston Pilot. Two years later, he became a co-editor there. Writing for New England’s growing Irish community, McGee promoted the movement for Irish self-determination led by Daniel O’Connell.

McGee’s work eventually caught the attention of O’Connell. In 1845, at the onset of the Irish Potato Famine, McGee returned to Ireland to fill a position at the Freeman’s Journal. That publication was closely linked to O’Connell’s party, the Repeal Association.

Around this time, McGee fell in with the Young Ireland movement. This was a group of nationalists who advocated for Irish emancipation. They were more revolutionary than the legislative approach taken by O’Connell. McGee soon began to butt heads with the Freeman’s editors. He resigned for a position at Young Ireland’s paper, The Nation.

In 1848, revolution swept across the European continent. McGee attempted to lead a rebellion for Irish independence. He travelled first to Scotland, where he hoped to find people sympathetic enough to the Irish cause that they would take up arms against London. When this failed to occur, he returned to Ireland and attempted to stoke rebellion in the country’s northeast. But this was also a complete failure. Dejected and now wanted by the authorities, he escaped to the United States in October 1848. He landed in New York, where he eventually established an American counterpart to The Nation.

Over the course of the subsequent decade, McGee paid increasing attention to Canadian politics. In his previous stint as an American journalist, his pro-Irish hatred of the British had dovetailed with pro-US hatred of the British. In some of his earlier editorials, he had even promoted a US annexation of British North America. “The United States of North America must necessarily in course of time absorb the Northern British Provinces,” he wrote. “A river like the St. Lawrence cannot safely be left in European hands. […] Either by purchase, conquest, or stipulation, Canada must be yielded by Great Britain to this Republic.”

Move to Canada East

Thomas D’Arcy McGee’s loyalty was first and foremost to the Irish community. The dramatic influx of Irish immigrants to the United States in the 1840s had spurred an anti-immigrant movement. It was led by a group called the “Know Nothings.” McGee’s opinions began to shift after a series of visits to Canada. He concluded that minority communities there enjoyed “far more liberty and toleration […] than in the United States.”

In response to the rise of Know-Nothingism, McGee began to advocate for an Irish colony on the Western frontier of Canada or the US. This project earned him the nickname “Moses McGee.” To accomplish his dream of an Irish colony, he organized a conference in Buffalo, New York, in 1856. It was attended by about a hundred delegates, 43 of whom were Canadian. But they ultimately failed to raise enough funds to claim a township. The endeavour was further complicated by opposition from influential Catholic leaders in New York.

This stoked previous tensions between the Catholic Church and McGee. Although a devout and conservative Catholic, McGee had blamed the Church for the failure of the Irish people to revolt in 1848. As he proceeded with the colonization project, American Bishops mocked him for suggesting that Canada could be any more liberal than the US since it was dominated by the Orange Order. McGee expressed confidence that the Canadian club was far more moderate than its militant counterpart in Ireland. He wrote that it “is far more political than religious and […] I am assured by the most respectable Catholics in Canada West that they have no better neighbours […] than these same Orangemen.”

As McGee’s biographer David A. Wilson has observed, some of McGee’s opponents were right to suggest that Canada was not more tolerant towards Catholics. In some areas, the Orange Order was very powerful and highly exclusionary. At the same time, the Canadian government had already begun to establish a framework for the accommodation of Catholics, especially in Canada East. Wilson writes, “There were so many local and regional variations that enough evidence could be found to support any predetermined position, positive or negative.”

McGee gradually became disillusioned with the United States. At the same time, some Canadian friends suggested that the Irish community there was in need of political leadership. In the spring of 1857, McGee emigrated to Montreal. He established a new publication called New Era, in which he promptly began to espouse the cause of Confederation.

Turn to Politics and Confederation

In December 1857, Thomas D’Arcy McGee was elected to the Province of Canada’s legislative assembly. He was one of three representatives for Montreal. In public life, as in his writing, McGee became a staunch supporter of Canadian nationhood. As biographer Alexander Brady has written, “To McGee nothing seemed more apparent than the fact that the Canadas should form the nucleus of a nation.” McGee established a publication and a new political career in under a year. He arguably became the most “fervid apostle of British American union and nationality.”

Through the remaining decade of his life, McGee’s political stances reflected his growing conservatism and respect for British Parliamentary democracy. Initially, he worked with the short-lived Reform government of George Brown. He later served in the moderate Reform government of John Sandfield Macdonald. But he defected to the Conservatives in 1861 to endorse a bill for separate Catholic schools. He eventually joined John A. Macdonald’s government as minister of agriculture, immigration and statistics.

In 1864, he helped organize a diplomatic tour of the Maritime colonies for delegates from the Province of Canada. His stump speeches in favour of British North American union on this tour supported his reputation as the most eloquent public speaker from the Canadas. (Two of his most famous speeches on Confederation were subsequently published.) He attended both the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences in 1864. However, he was excluded from the delegation sent to the London Conference in 1866. By that time, his political base was eroding.

Later Career and Assassination

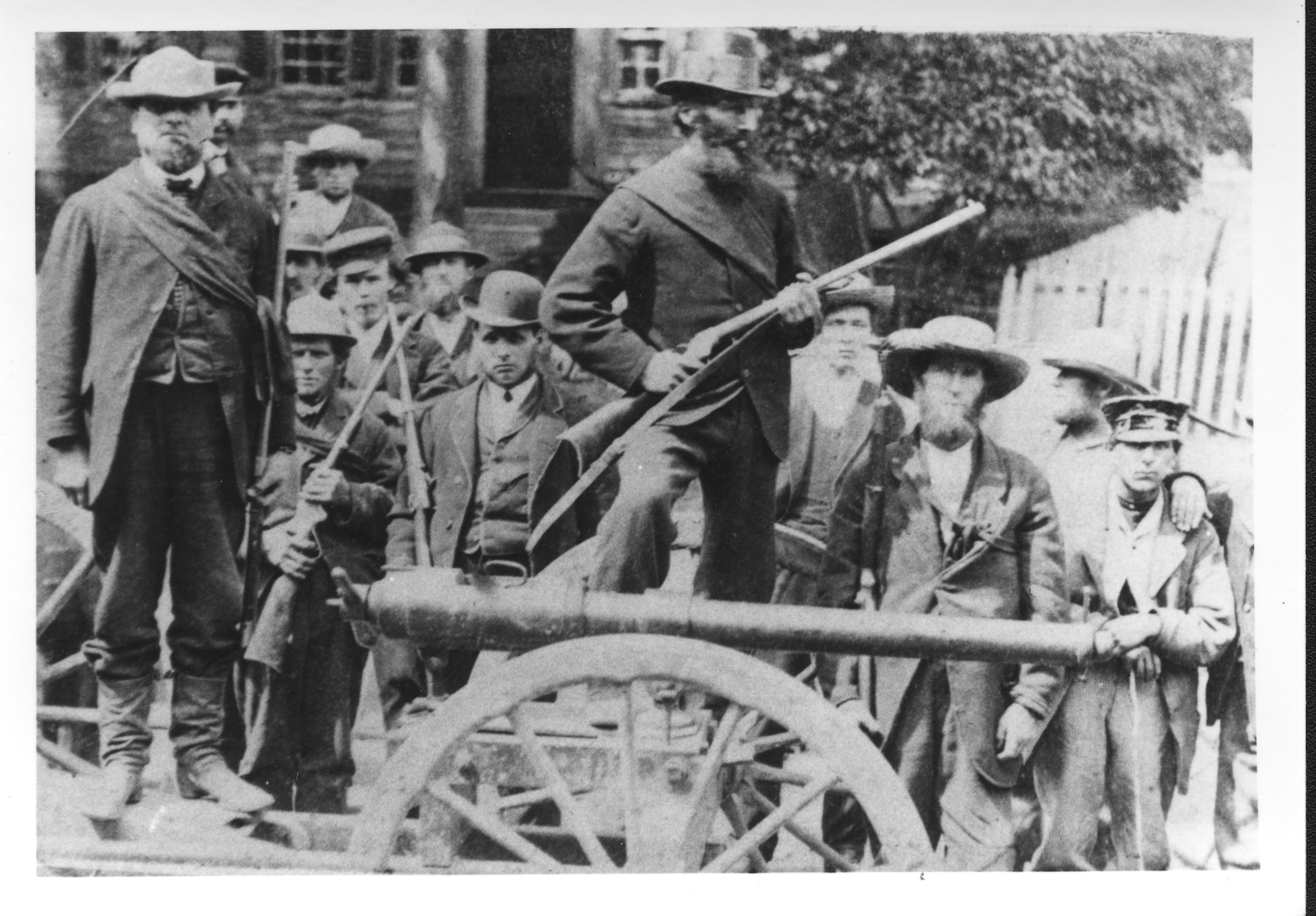

Thomas D’Arcy McGee’s popularity soon faltered. He began to publicly denounce the growing Fenian movement. It was an Irish national movement whose methods and objectives could easily have been based directly on McGee’s own revolutionary screeds. (See also Fenian Raids.) He encouraged the Irish national struggle to instead follow the Canadian model of (limited) self-government within the British Empire.

McGee was eventually seen as a traitor by the very Irish community he sought to defend. By 1867, he expressed a desire to leave politics. Sir John A. Macdonald had planned to appoint him commissioner of patents, to provide him with spare time to pursue his literary work.

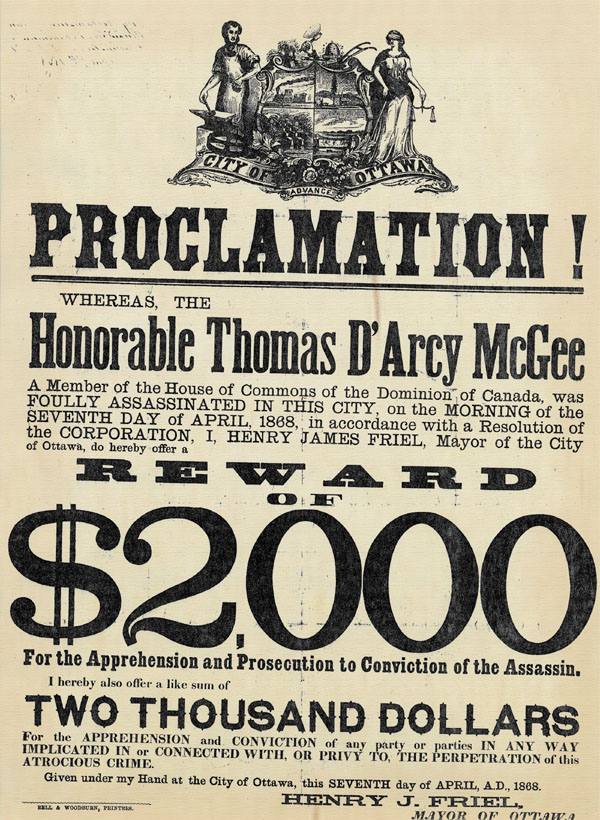

In the early hours of Tuesday, 7 April 1868, McGee was assassinated outside his Ottawa home. The authorities suspected a Fenian conspiracy and swiftly arrested Patrick James Whelan. Whelan maintained his innocence throughout his trial and was never proven to be a Fenian. Nonetheless, he was convicted of murder and hanged before more than 5,000 onlookers on 11 February 1869. (See also: The Assassination of Thomas D’Arcy McGee.)

Following McGee’s assassination, the Dominion Police was organized by the federal government in 1868 to guard the Parliament buildings in Ottawa. The service also provided bodyguards for government leaders and operated an intelligence service whose agents infiltrated the Fenian Brotherhood. The force was absorbed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in 1920.

Legacy

Thomas D’Arcy McGee’s popularity had declined by the time of his assassination. But his funeral brought an unprecedented crowd into the streets of Montreal. Held on what would have been his 43rd birthday, the funeral attracted tens of thousands of people.

McGee is generally remembered as an early advocate for minority rights at a time when the politics of ethnic and religious identity were intensely fraught. By all accounts, he was a uniquely gregarious character on the political scene and a passionate advocate for Canadian interests.

By the end of his life, he had written 10 books. These included two works of fiction and several extended historical essays. He also wrote hundreds of poems in the Romantic vein, many of which were published in his lifetime. After his death, 309 of them were collected and published by his friend Mary Anne Sadlier Madden.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom