Technology is the manipulation of the physical world to achieve human goals. Technological knowledge is often embodied in physical objects such as tools. Technologies affect and are affected by the society that uses them — in Canada, for example, Indigenous peoples developed different types of canoes depending on the type of water being travelled. Later, technology facilitated the colonization of the country through the development of agricultural tools, railroads and new forms of shelter. Today, Canada remains at the forefront of technological development in areas including transportation, communications and energy.

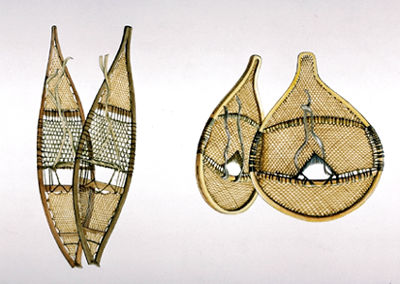

Indigenous Technologies

The technologies Indigenous peoples used to adapt to the regions of Canada, from the Great Lakes to the Arctic, depended greatly on geographical conditions and local resources. Notable achievements include: transportation technologies such as birchbark and cedar canoes, and the snowshoe; shelters such as the tipi, longhouse and igloo; and a variety of hunting and fishing technologies. These technologies did not remain static over time. Instead, they grew in range and sophistication allowing more and more successful exploitation of a variety of environments in the acquisition of food resources, the making of shelter and clothing, as well as engaging in trade and conflict.

Colonization and Settlement: 1500–1867

While the Vikings, sailing on sophisticated ships called knarrs, travelled to North America in the Middle Ages, Europeans from France, the British Isles and elsewhere began to explore and settle on the continent at the very end of the 15th century. They brought with them an inventory of tools and the know-how to use them. However, the new environment of northern North America required modifications to all of these technologies as fishing and trading outposts, agricultural settlements, roads and towns were established. In addition, Europeans had to adjust to using these tools in a new cultural setting. Whereas in Europe someone of high social standing often dictated tasks, in North America, tasks were performed more cooperatively, often led by the most skilled individual.

The international rivalry for Grand Banks cod resulted in the first English settlements in Newfoundland. These settlements were directly affected by existing fishing technology. While the French salted their catch immediately and sailed home without much contact with the land, the English, on the other hand, did not have cheap supplies of salt and were forced to establish drying platforms called flakes.

Agriculture

Mainland settlements were principally agricultural in nature, using and adapting European implements to a variety of challenging North American environments. Agricultural technology, more than any other, is profoundly affected by local conditions of weather, soil, water and pests, as well as land-tenure systems. Acadian farmers built dikes to protect their fields from flooding in the Fundy marshes. In New France, the seigneurial system created a pattern of long, narrow landholdings extending out from the St Lawrence River — a vital artery of travel and commerce. Loyalists in what would become Ontario cleared thick stands of trees and dense underbrush using simple, sturdy hand tools like the brush scythe and oxen as draft animals. Heavy plows (called "French" plows and similar to the medieval two-wheeled plow drawn by oxen) were first used by the Acadians and Habitants. A smaller, rugged implement called the bull plow, with no wheels or coulter, was developed for maneuvering around stumps and rocks. Alternately, a harrow was used to work the virgin soil lightly. Later, when stumps began to rot they could be pulled or blasted out. Gradually, iron was substituted for wood, and an all-iron "Scotch" plow was frequently imported to Canada.

Shelter

A major technical problem facing all settlers was shelter. Western European timber-frame construction, familiar to most colonists, was first used and adapted by the Habitants and Acadians. Loyalists, settling in the Maritimes and in Upper Canada, built houses of logs fastened together at the corners, making use of the abundant timber resource. Wood was not only the all-purpose material for shelter and tools — it often provided pioneer settlers with their first cash income in the form of potash, a chemical made from wood ashes.

Industry

Not all work was done by hand. The first water-powered grist mill in North America was built by Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt, lieutenant governor of Acadia, at Port-Royal in 1606. Eventually grist mills, flour mills and sawmills were found throughout the colonies; many were the nuclei of small villages. One state-of-the-art sawmill in Saint John, New Brunswick, has since been described as one of the most scientific in North America. Most mills were water powered; however, by the 1830s, steam powered sawmills started to appear. Bigger and more efficient, such mills did not need to be located near water. Eventually, mills were established to produce textiles and work iron. Coal was mined sporadically in Cape Breton beginning in the early 18th century. Beginning in 1733, bog iron ore was mined, smelted and processed at Forges du Saint-Maurice near Trois-Rivières, Québec, and later at Normandale in Upper Canada. In the 1840s, Nova Scotian Abraham Gesner invented kerosene, a fuel that replaced whale oil as a source of illumination in lamps. In Southwestern Ontario, petroleum extraction began in 1858, shortly before Americans began doing the same. Southwestern Ontario — the village of Oil Springs, in particular — also led the way in the chemical refining of crude petroleum in North America.

Transportation

Transportation, over huge distances and difficult terrain, posed enormous challenges. The birchbark canoe long used by Indigenous peoples, and adopted by French fur traders, linked the North American interior to the wider world. The Hudson’s Bay Company developed the York boat for the journey inland from Hudson Bay. Shipbuilding began in 17th-century New France with carpenters learning the skills of shipwrights. From the mid-18th century onward, government policy encouraged shipbuilding in the Maritime colonies. In 1809, John Molson financed the construction of the Accommodation — a steamship with a locally made steam engine to service the busy route between Montréal and Québec City.

The importance of water travel to colonial economies was increased by the building of canals. Attempts to overcome the rapids on the St Lawrence River began in the French regime and continued under British and Canadian colonial authorities. The Lachine Canal in Montréal was also a source of hydraulic power. Industries located along the Canal included the Redpath sugar refinery. The Rideau Canal, linking the Ottawa River to the St Lawrence and Lake Ontario, was constructed as a military works project after the War of 1812 under the direction of Lieutenant-Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers. The first Welland Canal, to overcome the formidable obstacle of Niagara Falls, was constructed in the 1820s using mostly American technology developed for the construction of the Erie Canal a decade earlier.

Construction of roads over the long distances between settlements was expensive, difficult and slow. By the end of the pioneer period some arterial roads were completed. Cedar logs were used to cover swampy stretches of road and gravel surfaces were laid where traffic was heaviest. In the 1840s, Canadians experimented with plank roads, using cheap forest products, but the winter ice and spring thaw left them in shambles. Only urban roads were paved, usually with crude cobblestones. Of greater importance was the coming of the railway, beginning with the Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad, also financed by John Molson. By 1860, most major communities in the Canadas were connected by the Grand Trunk Railway, while the St Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad joined Montréal with Portland, Maine. Railway technology also had an effect on bridge building. The tubular construction of the Victoria Bridge at Montréal, completed in December 1859, was an engineering marvel of the day. The railway shops where cars, locomotives and other equipment were made were the country’s largest manufacturing enterprises by the time of Confederation. Engineer T.C. Keefer, in his essay the “Philosophy of Railroads,” urged his fellow Canadians to appreciate not just the economic, but the social and cultural importance of that technology, a technology which would link them to the wider and modern world, not just move their goods faster.

National Development: 1867–1913

During this period, political as well as economic forces promoted the growth of railways, industrialization and settlement of the Prairies.

Agriculture

Farming, fishing and forestry were transformed by new technologies of production and processing. Clay drainage tiles in the rainy East and wooden irrigation flumes in the dry West increased the productivity of land. New varieties of hardy, early ripening wheat and harvest excursion trains to bring in much needed seasonal labour began the transformation of the prairies to a granary for the world. The introduction of rolling mills, which processed hard western wheat more quickly, radically changed flour milling. One of the first roller mills was the E.W.B. Snider mill in St Jacobs, Ontario, in the 1870s. The Ogilvie Flour Milling Co, founded in 1801, built a huge new plant in Montréal in 1886, incorporating the latest reduction roller mills. Cheese factories in Ontario and Québec turned out products that supplied local and world markets, as did pork-packing facilities in Toronto. As farming continued to mechanize, firms such as Massey, Harris and the Cockshutt Plow Company developed a full line of farm machinery for most operations and sought wider markets. Together, Canadian and American manufacturers created a common pool of agricultural equipment that freed farmers from colonial-era dependence on European technology.

Fishing

By the 1860s, Atlantic fishing technology had been changed by the introduction of the longline or "bultow." Refrigeration and railways increased the fresh-fish market. On the Pacific coast, gillnetting harvested enormous numbers of salmon, which mechanized butchering and canning facilities processed into a readily exportable product. Government and university-based research investigated and offered solutions to many of the technical problems associated with harvesting and processing fish and other seafood.

Forestry

Lumbering continued in eastern Canada, joined by British Columbia, with provincial governments increasingly encouraging the milling of logs into lumber domestically rather then exporting them to the United States. While paper had been manufactured from textile scraps (“rags”) in Canada as early as 1804, new mechanical and chemical techniques for pulping wood transformed the industry beginning in the 1860s (see Pulp and Paper Industry).

Mining

While the Fraser, Cariboo and Yukon gold rushes were dramatic, the discovery of base metal deposits had more lasting technical implications. Metallurgical techniques were often the final key to unlocking the wealth of these mines. The Orford process was used to separate the copper-nickel ores of the Sudbury Basin, while differential flotation was used to extract the complex ores, containing mostly lead and zinc, at the smelter in Trail, British Columbia.

Transportation

Canals were recognized as efficient carriers of bulk cargo, and as shipping increased on the Great Lakes improvements were needed. In Nova Scotia, the long-awaited Shubenacadie Canal, connecting the Bay of Fundy and Dartmouth, was opened in 1861. Starting in the 1870s and continuing into the 1880s, the Welland Canal was rerouted and deepened, first to 12 feet (3.65 m) and then to 14 feet (4.26 m). A canal was opened at Sault Ste Marie in 1895 and the Soulanges Canal in Québec opened in 1899. More construction on the Trent Canal facilitated the development of Central Ontario. The Peterborough lift lock, designed by R.B. Rogers, was the largest of its kind in the world and an outstanding engineering achievement.

Completion of the Intercolonial Railway in 1876 fulfilled a condition of Confederation by joining central Canada to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Construction first of the Canadian Pacific Railway and then two other transcontinental lines through the difficult rock and muskeg of the Canadian Shield, across the prairies and through the Rockies, became one of Canada's greatest engineering feats. Some of the world's first cantilever bridges were constructed over the Niagara and Fraser rivers in 1883 and over the Saint John River in 1884.

Communications

Communication technology advanced rapidly with the electric telegraph, ushered in as a companion to the railways starting in the 1850s. Alexander Graham Bell's telephone appeared in the 1870s and, by the 1880s and 1890s, exchanges were common in most large cities. The first telephone exchange in Canada was installed in 1878 in Hamilton and it had 40 telephones by the end of the year. The first automatic exchange, allowing users to phone each other directly rather than with the assistance of an operator, was installed in Whitehorse by the Yukon Electric Co in 1901. The first transatlantic wireless telegraph (radio) signals were transmitted by Italian engineer Guglielmo Marconi in 1901, while Canadian Reginald Fessenden may have been the first to successfully send audio (voice) radio signals in 1906.

Urban Development

In the 1880s, Canadian cities began to grow beyond the size where everyone could walk to work and public transportation was needed. Horse-drawn omnibuses were followed by horse-drawn streetcars on rails. While the technology was displayed at the Toronto exhibition grounds in 1884, the first Canadian cities to have electric streetcars were Windsor (1886) and St. Catharines (1887), making them among the earliest North American cities to adopt this new form of public transit.

Urban areas also require large supplies of water for domestic and industrial use, as well as fire protection and a system to handle waste disposal. By the 1870s, the water supplies of most large cities were pumped by steam; by 1900, some were using sand filters or hypochlorite of lime for water treatment. Sanitation services improved as better sand filters cleansed city drinking water, but sewage treatment advanced slowly. In 1915, Brantford, Ontario became the first municipality in North America to construct an activated sludge plant — where microrganisms are used to break-down organic matter — for the treatment of sewage. While wood remained a common material, new building techniques incorporating structural steel and reinforced concrete as well as elevators also helped cities to grow upward as well as outward.

Industry

Steam engines not only transformed transportation, but when applied to industry and agriculture, gave a much more flexible power source. Electrical power, electric lighting and electric motors for machinery gave even more flexibility in industrial production. In Canada, the Second Industrial Revolution arrived hard on the heels of the first as new industries based on chemistry and electricity grew in importance. The rapid expansion of electrochemistry in the 20th century permitted the economical production of many chemicals. A Canadian, Thomas Willson, developed the first successful commercial process for manufacturing calcium carbide. The first plant was established in Merritton, Ontario, in 1896. Shawinigan, Québec emerged as an important electrochemical centre, first producing carbide and then also aluminum. The first contact sulphuric acid plant was established at Sulphide, Ontario, in 1908. Salt deposits in Southwestern Ontario were exploited by the Canada Salt Company in Sandwich (now part of Windsor) to manufacture caustic soda and bleaching powder, and later soda ash, liquid chlorine, and hydrochloric acid.

The farm machinery industry grew dramatically, employing new sources of power, as well as new methods of manufacturing and assembly. In addition, the railway allowed for machinery to be more widely distributed. Engine and tool companies were established to provide machinery to the railway and forestry industries. The changeover from iron rails to steel started in the early 1870s. While much early railway steel was imported, in the early years of the 20th century the production of rails by Canadian steel mills grew spectacularly.

Formal engineering education began slowly with civil engineering at King's College, Fredericton, in 1854; McGill in 1871; the School of Practical Science in Toronto in 1873; École Polytechnique in Montréal in 1873; Royal Military College, in Kingston, Ontario, in 1876; and the School of Mining and Agriculture, at Queen's University in 1893. Most of these universities offered courses in civil, mining and mechanical engineering, and quickly added electrical and chemical engineering programs. University-level forestry programs were also established at several universities.

First and Second World War: 1914–50

In spite of the First and Second World Wars and the Great Depression, the first half of the century brought unparalleled agricultural and industrial development and prosperity. With the advent of the internal combustion engine, Canadians became second only to Americans in their use of the automobile, while bush flying helped open the Canadian North. Radio was a new medium not just of communication, but also entertainment. The Canadian Standards Association, which originated during the First World War, played a major role not just in aiding uniformity of technical practices in industry across Canada, but in ensuring technological compatibility between Canadian and US goods.

Agriculture

Farming increasingly became a blend of tradition with new mechanical skills. The gasoline tractor, combine harvester and new specialized machinery, like row cultivators for tobacco and corn crops, appeared in Canadian fields. The new technologies of pasteurization, refrigeration and the commercial canning of meat, vegetables and fruit, as well as condensed milk and processed cheese, helped provide food to growing urban areas.

Transportation

Canada’s rail system continued to expand with the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway (Ontario Northland) constructed from 1903 to 1931 and extending from North Bay to James Bay, Ontario. The Hudson Bay Railway, which opened in 1929, was built to open another saltwater port, at Churchill, Manitoba, providing access to prairie grain. The increased size and number of ships on the Great Lakes made the New Welland Canal obsolete and a larger, more direct canal, called the Welland Ship Canal, was started in 1913, was interrupted by the war and officially opened in 1932.

Cars and trucks passed from being curiosities to necessities. The building of highways was facilitated by a new generation of trucks and crawler tractors, adapted for road construction. The Queen Elizabeth Way around the western end of Lake Ontario connecting Toronto to Buffalo, New York, via the Peace Bridge at Fort Erie was North America’s first intercity, limited access superhighway. Public transport was vital to the growing cities with electric trams first joined then slowly replaced by diesel buses. Joseph-Armand Bombardier's pioneering snowmobile offered increased mobility and later recreation in snow-bound rural areas.

The first powered, heavier-than-air flight in Canada was the Silver Dart in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, in 1909. After the First World War, surplus military aircraft were quickly adapted to peacetime tasks, often associated with lumbering and mining in northern areas. In 1920, a federal government agency, the Associate Air Research Committee, was established to foster aeronautical research in Canada. In the 1920s, W.R. Turnbull perfected the electrically operated variable-pitch propeller, which was adopted around the world. The most famous of a new generation of bush planes was the Noorduyn Norseman. During the Great Depression, one of the government's most successful, innovative, make-work programs involved building a string of airports across the country.

Hydroelectricity

The pioneering 19th-century development of hydroelectricity at Niagara Falls was followed by ambitious projects there and elsewhere. Ontario Hydro’s Queenston–Chippawa power generation project (under construction from 1917 to 1921) was the largest engineering project since the completion of the Panama Canal. As well as providing light and power to urban areas and factories, many hydroelectric developments were closely tied to mining, pulp and paper, and aluminum processing.

Industry

Another important technology was the manufacture of artificial fibres. The production of viscose rayon in Canada was started by the British firm Courtaulds in Cornwall, Ontario, in 1925. The process used cellulose from wood pulp. In 1928, Canadian Celanese Ltd started to manufacture cellulose acetate rayon at Drummondville, Québec. Canadian Industries Ltd began to manufacture cellophane at Shawinigan Falls in 1931. The discovery, at McGill University, of a method to extract vanillin from pulp mill waste eventually saw Canada providing 60 per cent of the world’s supply of what had been a scarce natural product.

Communications

Vacuum-tube telephone repeaters improved long-distance communication, making possible the TransCanada Telephone System, formally opened in 1932. During the 1920s and 1930s, most urban areas of Ontario and Québec were converted to automatic, direct dial telephone service. By 1927, Canadians could telephone Europe via the US and, by 1931, direct connections were possible. Inventor Edward Rogers, Sr. made important contributions to radio technology, while Reginald Fessenden was a pioneer of television technology.

Domestic Technologies

New technologies also found their way into the homes of Canadians in the form of washing machines, vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, gas and then electric ranges and other appliances. While advertised as labour saving, it is unlikely that they reduced, and may have even increased, the amount of time women spent on housework.

Contemporary Canada: 1950–Present

Canada emerged from the Second World War as a middle power and continues to rank among the strongest of the world’s economies. Canada has remained at the forefront of technology as a user of technologies developed elsewhere, but also as a developer and manufacturer of advanced high-tech items.

Energy

Pitchblende, a once obscure ore from which radioactive radium could be refined, became a strategic source of uranium during the Second World War. Mined near Great Bear Lake and refined at Port Hope, uranium became, along with Saskatchewan potash and Alberta petroleum, one of a trio of new staple products.

To feed the demands of industry and growing cities for power massive new hydroelectric projects literally altered the landscapes of Northern Québec and the British Columbia interior. Thermoelectric stations were built in the Maritimes and the Prairie provinces. Ontario opened the first nuclear-powered thermal station in Rolphton in 1962. Natural gas exploration continued in Alberta and Saskatchewan following the Leduc oil field discovery in 1947. The oil industry became complex, producing gasoline, diesel, heating fuels and heavy oils for lubrication, as well as developing the huge petrochemical industry with its hundreds of by-products. Sarnia and Montréal became centres of the petrochemical industry, although gradually some industry shifted closer to the oil fields. The success of the Alberta oil sands made Fort McMurray a boom town (though one heavily damaged by fire in 2016). Proposals to move liquefied natural gas by pipeline to coastal British Columbia for export have faced environmental objections as has the building of new pipeline capacity south to the United States.

Transportation

Two postwar transportation megaprojects had profound influence on Canada. The first was the St Lawrence Seaway, a joint Canada-US transportation and power development scheme completed in 1959. It allows bulk goods to travel by water from the interior of the continent to the Atlantic Ocean. Second, the opening of the Trans-Canada Highway in 1962 signalled the victory of personal cars over passenger rail as Canadians' preferred mode of travel. In addition, Toronto’s first subway line opened in 1954, followed by Montréal’s first line in 1966. Buses and Light Rail Transit supplemented transit systems in these and other Canadian cities.

While Asian car companies joined those of the United States in building manufacturing plants in Canada, an attempt to develop and build a Canadian high-performance sports car, the Bricklin SV-1, was a commercial failure. Although retaining a considerable capacity to repair and refit vessels, postwar shipbuilding dwindled until only a few lake carriers and saltwater fishing boats were produced. Canadian shipyards have already produced some of the most advanced icebreakers and, with increased exploration for oil, gas and minerals in the Arctic, this technology has great potential.

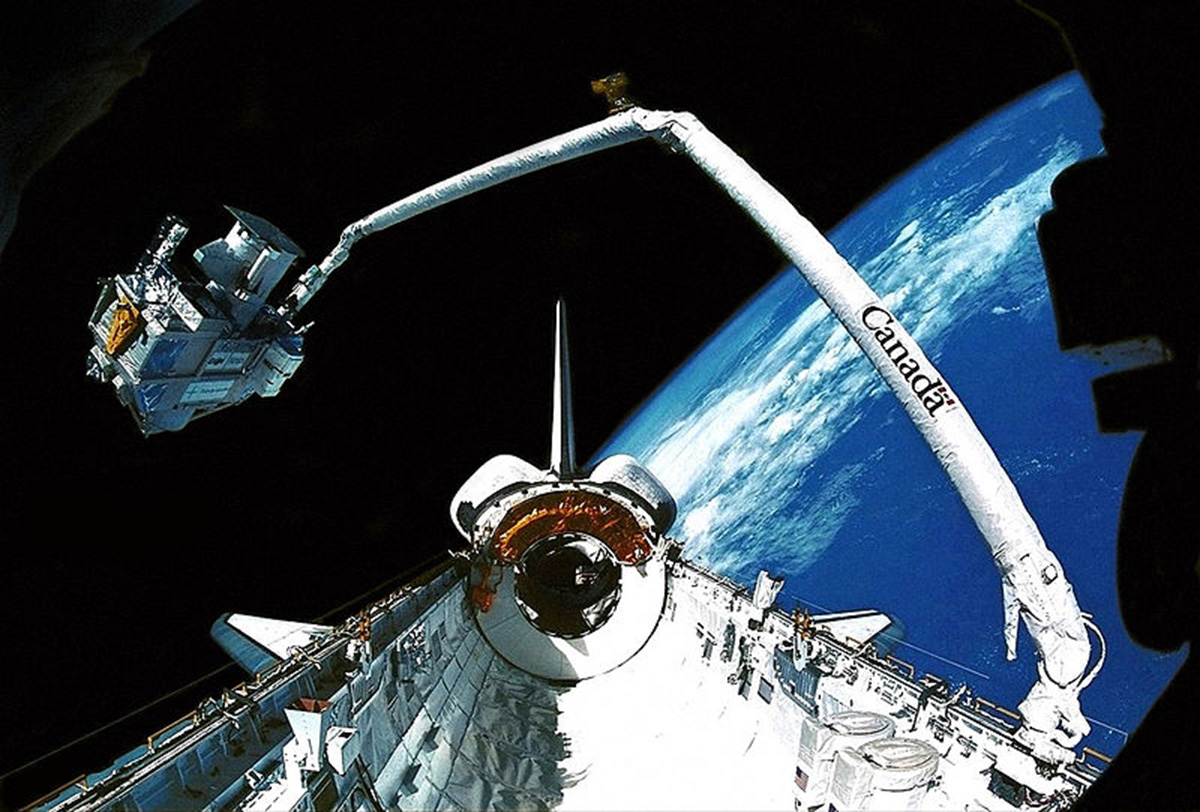

Aerospace

Discussions of the Canadian aviation industry too often focus on the cancellation of the Avro Arrow jet fighter program in 1959 to the neglect of many other important strengths of the Canadian aerospace sector. The Canadian aircraft industry continued to develop innovative STOL (short take-off and landing) aircraft, such as the Otter, Dash 7 and Dash 8. Bombardier’s aerospace division is one of the largest aircraft manufacturers in the world with sales in the billions of dollars worldwide. Bombardier and the US–owned aircraft engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney Canada are among the most research-intensive companies in Canada. From the 1962 Alouette 1 satellite to the present Canadarm2 of the International Space Station, Canadian technology has a strong presence in outer space.

Canadian nuclear technology includes domestic nuclear power plants, the CANDU reactor and the Chalk River Laboratories, the latter of which produces a large share of the world’s medical radioisotopes. Other examples of Canadian technology-based science include the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory and the Canadian Light Source in Saskatoon.

Communication

Canadian contributions of computer technology include the WATFOR compilers developed at the University of Waterloo and widely used in computer education in the 1970s and 1980s. In addition, Canadian James Gosling invented the JAVA programming language. Waterloo, Ontario-based Research in Motion developed the BlackBerry smartphone and, along with IBM Canada, is also among the top 10 biggest corporate spenders on research and development in Canada.

In the realm of entertainment, the IMAX motion picture technology was developed as a commercial success, building on earlier work for the National Film Board of Canada. Television is available even in the remotest parts of Canada thanks to the Anik series of satellites. Canadian scholars were also notable as postwar analysts and critics of technology, in particular, University of Toronto professors Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan — two men who gained international reputations for their ideas about media and communications.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom