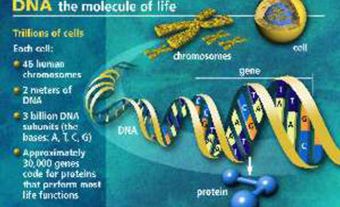

Stem cells are the body's "building blocks"; they are the cells from which all tissues and organs are derived. They have the ability to divide while still maintaining their identity, yet they can also develop into specialized cells in response to certain stimuli. They can be found in a wide range of tissues in mammals at different stages of development and in adult organisms in tissues like nerve, muscle and skin. Stem cells from adults have a more restricted range of development. In order to develop new treatments for specific conditions scientists must understand more about how cell differentiation is directed by biological signals. New methods need to be found to grow large numbers of desired cells and more scientific experimentation involving different types of stem cells is vital. It will take many years for research projects to provide sufficient knowledge about stem cells to make new treatments possible (see Medical Research).

Background

Scientists have been conducting research into stem cells for much longer than most people realize. The existence of stem cells was proven in 1961 by Canadian scientists James Till and Ernest McCulloch. Their paper on what were then called colony-forming cells was the breakthrough that started stem cell science. Their work was followed in 1978 by the discovery in the US of hematopoietic stem cells in the blood of human umbilical cords.

Medical research into stem cells in Canada has seen many milestones over the years. One of the earliest occurred in 1992, when Dr. Sam Weiss of the University of Calgary identified stem cells in the adult human brain. He discovered that the adult brain produces stem cells to heal itself. In 1994, at the University of Toronto, Dr. John Dick isolated the first cancer stem cell from a leukemia patient, producing the first direct evidence for cancer stem cells. Also in 1994 at the University of Toronto, Dr. Derek van der Kooy identified retinal stem cells in mice.

A major breakthrough in the field occurred in the United States in 1998 when James Thomson developed stem cells from human embryonic and fetal tissue. Stem cells with the greatest research potential are from the stage immediately after the union of ovum and sperm. These cells are called totipotent or pluripotent and can become any of the 300 different types of cells that comprise the adult human body. Stem cell therapy may eventually treat previously incurable and devastating conditions such as stroke, certain types of cancer (leukemia, lymphomas, lung cancer), muscular dystrophy, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Diabetes, Heart Disease and spinal cord injuries.

Stem Cell Research

Stem cell research also contributes to broader understanding in other areas. For example, research into multiple sclerosis treatments contributes to understanding the biological mechanisms underlying a wide variety of other autoimmune diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and lupus). In the future one treatment may be useful for multiple diseases.

The potential for such treatments is evident in the progress made in the area of diabetes treatment. In 1999 the Edmonton Protocol was developed for the treatment of Type 1 diabetes. It involves the implantation of pancreatic islets, which has been done successfully for many patients. However, harvesting enough islets is hampered by a limited number of organ donations and the requirement for the donation of two pancreases to provide enough islets for one patient. Even increasing the efficiency of the islet extraction process will leave the majority of people with Type 1 diabetes untreated. Scientists are working to find a way to mass-produce islets from stem cells in the laboratory. This could be done by identifying the adult stem cells that make islets or by training embryonic stem cells to become islets.

Stem cells also have potential applications in pharmaceutical research. Human stem cells could be used in drug design and testing to evaluate medication safety and efficacy in a human model instead of an animal model. Research using animal models is complicated by the need to translate specific results from animal reactions to reactions in humans. The development of a human model for research could significantly reduce the number of years it takes to develop new medicines.

Morality, Ethics and Stem Cell Research

Stem cell research holds vast therapeutic promise, but possible benefits must be weighed against ethical concerns (see Medical Ethics). Controversy is endemic to scientific research; whether concerns outweigh the benefits depends largely on opinion. Ethical concerns include the potential for a profit motive for stem cell research, whether the proposed research is scientifically worthy, and whether researchers conduct such projects responsibly.

The biggest issue is over the source of embryonic tissue. Stem cells can be derived from surplus embryos created by in vitro fertilization treatments, from fetal tissue that results from elective abortions and from gametes (ova or sperm) used in medical research. Fertilized ova--blastocysts--are clusters of cells, the status of which is at the core of this controversy. Some argue that, as a potential person, a blastocyst deserves the full respect and protection afforded to a person. Others argue that, while a blastocyst is genetically human, it has none of the characteristics of a person--it is not conscious or self-aware. A third opinion holds that, while the blastocyst is clearly not a person, it is part of the life cycle and so ought to be treated with a degree of respect.

Canadian Guidelines for Stem Cell Research

People have a wide range of views on the subject of stem cell research and Canada has endeavoured to develop guidelines that respect this diversity. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) developed guidelines in 2002 for the use of stem cells in research in Canada. Great attention was paid to developing rules and regulations that would permit important medical research while respecting the ethical concerns of Canadians. Canadian medical research guidelines specify that stem cell projects must have informed consent from adult donors of sperm and ova. In other words, in the case of a couple opting for in vitro fertilization, both the man who donated the sperm and the woman who donated the ova must consent to the surplus embryos being used for stem cell research. If a single woman is using in vitro fertilization then only she must consent to the use of excess embryos.

All research projects falling under these guidelines must offer potential health benefits for all Canadians rather than a specific group. In addition, the research must respect the privacy and confidentiality of each party involved in the research. Canadian guidelines specifically prohibit financial motive in stem cell research or from the embryos used in such research. The guidelines regulating the source of embryos specify that embryos cannot be created specifically for any use in stem cell research. Guidelines in Canada specify that research is permitted only during the first 14 days after the union of ovum and sperm. Research that would combine non-human cells with human embryos is prohibited.

Exactly how stem cell research will develop in the future is unknown. Currently there are particular areas of interest, but new interests and issues will undoubtedly arise. As stem cell research develops further, new and unexpected ethical concerns may occur. These concerns will need to be addressed by new or modified guidelines.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom