South Asians trace their origins to South Asia or the Indian subcontinent, which can include India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Most South Asian Canadians are immigrants or descendants of immigrants from these countries, but immigrants from South Asian communities established during British colonial times also include those from East and South Africa, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Fiji and Mauritius. Others come from Britain, the US and Europe. In the 2021 census, 2.6 million Canadians (7.1 per cent) identified as being South Asian.

Overview

According to the 2021 census, South Asians are the largest visible minority population group in Canada. Among South Asian Canadians, 44.3 per cent were born in India, 28.7 per cent in Canada, 9.2 per cent in Pakistan, 5.4 per cent in Sri Lanka and 3 per cent in Bangladesh.

People referred to as South Asian share cultural and historical characteristics, however their identification is often more specifically tied to their ethnocultural roots.

Origins

The ethnic diversity of South Asian Canadians reflects the enormous cultural variability of South Asia's people. The majority of South Asian Canadians were born in India, where many languages and hundreds of discrete ethnic groups exist. This pluralism extends to religion; although the majority of Indians are Hindus, many practise Islam and Sikhism. Many others are Christian or Jain. Islam is the predominant religion in Pakistan and Bangladesh, yet both countries are culturally diverse. A third major world religion, Buddhism, is practised by many Sri Lankans, but large Hindu, Christian and Muslim religious minority groups exist among Sri Lankans as well.

Immigration

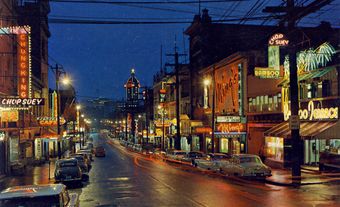

The first South Asian migrants to Canada arrived in Vancouver in 1903. The great majority of them were Sikhs who had heard of Canada from British Indian troops in Hong Kong, who had travelled through Canada the previous year on their way to the coronation celebrations of Edward VII. Attracted by high Canadian wages, they soon found work. Immigration increased quickly thereafter and totaled 5,209 by the end of 1908; all of these immigrants were men who had temporarily left their families to find employment in Canada. Perhaps 90 per cent were Sikhs, primarily from Punjab farming backgrounds. Virtually all of them remained in British Columbia.

Seeing in them the same racial threat as it saw in Japanese Canadians and Chinese immigrants before them, the BC government quickly limited South Asian rights and privileges. In 1907 South Asians were provincially disenfranchised, which denied them the federal vote and access to political office, jury duty, the professions, public-service jobs and labour on public works. In the following year, the federal government enacted an immigration regulation that specified that immigrants had to travel to Canada with continuous-ticketing arrangements from their country of origin. There were no such arrangements between India and Canada and, as was its intent, the continuous-journey provision consequently precluded further South Asian immigration. This ban separated men from their families and made further growth of the community impossible.

Vigorous court challenges of the regulations proved ineffective, and in 1913 frustration with government treatment culminated in the evolution of the Ghadar Party, an organization that aimed to overthrow British rule in India. The immigration ban was directly challenged in 1914, when the freighter Komagata Maru sailed from Hong Kong to Canada with 376 prospective South Asian immigrants. The continuous-ticketing requirement that was enacted to prevent immigration from ships such as the Komagata Maru had the desired effect and prevented immigration of its passengers: the ship had not arrived directly from India but had come to Canada via Hong Kong, where it had picked up passengers of Indian descent from Shanghai, Moji and Yokohama. Immigration officials isolated the ship in Vancouver harbour for two months, and it was forced to return to Asia. Revolutionary sentiment thereafter reached a high pitch, and many men returned to India to work for Ghadar.

The federal government's continuous-journey provision remained law until 1947, as did most British Columbia anti-South Asian legislation. Because of community pressure and representations by the government of India, Canada allowed the wives and dependent children of South Asian Canadian residents to immigrate in 1919, and by the mid-1920s a small flow of wives and children had been established. This did not counter the effect of migration by South Asian Canadians to India and the US, which by the mid-1920s had reduced the South Asian population in Canada to about 1,300.

During the 1920s, South Asian economic security increased, primarily through work in the lumber industry and the sale of wood and sawdust as home heating fuel. In addition, a number of lumber mills were acquired by South Asians, two of which employed over 300 people. The effects of the Great Depression on the community were severe but were mitigated by extensive mutual aid. By the Second World War, South Asians in British Columbia had gained much local support in their drive to secure the vote, especially from the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. In 1947, the British Columbia ban against voting, as well as other restrictions, were removed.

Faced with the coming independence of India, the federal government removed the continuous-passage regulation in the same year, replacing it in 1951 by an annual immigration quota for India (150 a year), Pakistan (100) and Ceylon (50). At that time there were only 2,148 South Asians in Canada. Moderate expansion of immigration increased the Canadian total to 6,774 by 1961, then grew it to 67,925 by 1971. By 2011 the South Asian population in Canada was 1,567,400.

As racial and national restrictions were removed from the immigration regulations in the 1960s, South Asian immigration mushroomed. It also became much more culturally diverse; a large proportion of immigrants in the 1950s were the Sikh relatives of pioneer South Asian settlers, while the 1960s also saw sharp increases in immigration from other parts of India and from Pakistan. By the early 1960s, two-thirds of South Asian immigrant men were professionals — teachers, doctors, university professors and scientists. Canadian preferences for highly skilled immigrants during the 1960s broadened the ethnic range of South Asians and hence decreased the proportion of Sikhs. Non-discriminatory immigration regulations enacted in 1967 resulted in a further dramatic increase in South Asian immigration.

In 1972, all South Asians were expelled from Uganda. Canada accepted 7,000 of them (many of whom were Ismailis) as political refugees. Thereafter a steady flow of South Asians have come to Canada from Kenya, Tanzania and Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly known as Zaire), either directly or via Britain. The 1970s also marked the beginning of migration from Fiji, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago and Mauritius. During 1977–85 a weaker Canadian economy significantly reduced South Asian immigration to about 15,000 a year.

Religious and Cultural Life

South Asian communities vary widely in the emphasis they place on extra-familial cultural activities and religious institutions. For example, Sikhs are numerous, their identity is both ethnic and religious, and their religious institutions have been in place since the first Canadian Sikh temple was founded in 1908. They have consequently been very successful in establishing and preserving their religion in Canada. (See also Sikhism.)

Ismaili Muslims are also both an ethnic and a religious group that has founded strong religious institutions. Canada's South Asian Sunni Muslims (chiefly from Pakistan and India) have generally allied themselves with other Sunnis in support of pan-ethnic mosques, and they too have effectively transmitted their religion to their children. In Hindu populations of sufficient size, people have established both community-specific and multi-community Hindu temples, which are used by a range of different ethnic groups for prayer, for the presentation of annual ceremonies and for important rituals linked to marriage and death. Sinhalese who practise Buddhism established their first temple in Toronto.

Most communities support a variety of other activities and institutions. Nominally religious organizations frequently support language classes for children and cultural activities such as South Asian music and dance. In addition, there are many South Asian socio-cultural associations in Canada. Folk and classical music and dance traditions are popular. In addition, South Asian Canadians now support newspapers and newsletters across Canada. South Asian programming on radio and cable television has expanded rapidly with dedicated programming and channels, especially in major centres.

Politics

Until 1965, South Asian politics were devoted primarily to lobbying for the elimination of the legal restrictions enacted by the BC Legislature and to changing immigration laws. Since then, South Asians have become increasingly involved on other political fronts. Their associations now actively lobby for government support for cultural programs, for greater access to immigration, and for government action to reduce prejudice and discrimination. South Asians have frequently held municipal level offices, but their federal participation was not extensive until the 1980s. Sixteen South Asians ran for federal office in 1993, and British Columbia had two South Asian provincial cabinet ministers in the same year. South Asians are sometimes involved in home country politics; for example, Canadian Sikh communities provided support for the post-1983 rights for Sikhs in Punjab.

Cultural Preservation

In 1994, approximately 80 per cent of South Asian Canadians were immigrants. Only the Sikhs have been in Canada long enough to have demonstrated a clear pattern of cultural preservation through the generations. Strong group consciousness and minority-group status resulted in high rates of cultural retention among British Columbia Sikhs. Virtually all of the second generation are knowledgeable about Sikh culture and language and marry other Sikhs.

Other groups, e.g., Ismailis, Pakistanis and other Sunni Muslims, have stressed religion above cultural and linguistic maintenance. For most South Asian groups, acculturation in the second generation appears extensive, partially due to South Asian patterns of marriage and family maintenance. Whether social integration will be equally thorough will depend chiefly on the future development of relations between South Asians and other Canadians.

Settlement Patterns

Until the late 1950s, virtually all South Asians lived in British Columbia, but when professional South Asian immigrants came to Canada in larger numbers, they began to settle across the country. British Columbia's South Asian population in 2016 was 363,885, mostly concentrated in the Vancouver area. Significant numbers of people with South Asian origins live in Ontario (1,182,845), Alberta (231,550) and Quebec (95,670).

Economic Life

Early Sikhs in British Columbia were almost exclusively involved in the lumber industry. They are still active in this industry, both as workers and mill owners. Skilled South Asian professionals of various ethnocultural backgrounds who arrived between 1960 and 1985 are now well established. The occupational distribution broadened in the 1970s with the arrival of an increasing proportion of South Asian blue- and white-collar workers. The exodus of Ugandan South Asians brought many business people to Canada, many of whom undertook entrepreneurial activities ranging from the ownership of taxis to the control of corporations. The participation of other South Asians in businesses has also been high. In South Asia, few middle class women worked outside the home until the 1990s, but Canadian South Asian women have steadily become active participants in the economy in a variety of blue- and white-collar jobs. South Asians have also been involved in farming, especially in British Columbia.

Social Life and Community

South Asian Canadians have such widely varying backgrounds that few generalities can be made about their social and community life. One critical cultural commonality is that they all come from places where extended families, kinship and community relations are extremely important. Generally, immigrants from South Asia quickly accept many Canadian cultural patterns, but they have tried to maintain a core of continuity in family and community practice. Parents generally attempt to instill in their children key South Asian family values. This goes hand in hand with massive acculturation among the population who are Canadian-born. Husband-wife relations are changing, especially as wives acquire increased access to economic and social resources.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom