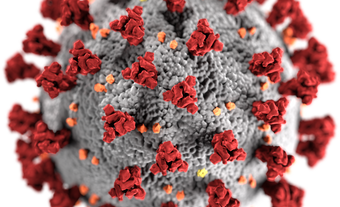

Smallpox is an infectious disease caused by the variola virus. The disease arrived in what is now Canada with French settlers in the early 17th century. Indigenous peoples had no immunity to smallpox, resulting in devastating infection and death rates. In 1768, arm-to-arm inoculation became more widely practised in North America. By 1800, advances in vaccination helped control the spread of smallpox. Public health efforts also reduced rates of infection. In the 20th century, Canadian scientists helped the World Health Organization eradicate smallpox. Eradication was achieved in 1979, but virus stocks still exist for research and safety reasons.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

A woman with smallpox in Prince Edward Island, c. 1909.

What Is Smallpox?

Smallpox is an infectious disease most commonly caused by the variola major virus. Its symptoms include fever, headache, vomiting, mouth sores and an extensive skin rash. The rash blisters and scabs, leaving pitted scars or “pocks.” Smallpox can cause pneumonia, blindness, and infection in joints and bones. There is also a less virulent form of smallpox called alastrim, caused by the variola minor virus.

Smallpox spreads in saliva droplets and through contact with the infectious rash. It can be passed between people and from contaminated objects to people. The rate of death from variola major is 30 per cent but from variola minor it is 1 per cent or less.

Smallpox Epidemics in New France

Smallpox crossed the Atlantic Ocean when European empires began to expand in the 16th century. The disease had long decimated populations and caused terror. It was first reported in New France in 1616 near Tadoussac, the colony’s first fur-trading post. The budding fur trade repeatedly exposed nearby Innu and Algonquin communities to the disease. Many fell ill and died due to their lack of immunity. The disease spread into the Maritime, James Bay and Great Lakes regions.

Between 1634 and 1640, Jesuit priests introduced smallpox into Wendake (Huronia), west of Lake Simcoe and south of Georgian Bay. Priests insisted on baptizing sick and dying Huron-Wendat. However, the priests’ presence contributed to the spread of the disease. Due to smallpox and other infectious diseases, the Huron-Wendat population declined by roughly 60 per cent by 1640.

Smallpox played a large role in the struggles between the French, British and Americans to control the St. Lawrence region. In 1732–33, a smallpox epidemic swept through Louisbourg, a French settlement in what is now Nova Scotia. It killed at least 150 people, including people the French had enslaved and brought to the colony. Another epidemic hit Louisbourg in 1755. This was the worst epidemic in New France. It was part of a larger epidemic that swept across North America between 1755 and 1782. During the Seven Years’ War, an outbreak forced de Vaudreuil, the French commander, to delay his invasion of Fort Oswego in what is now New York State. In 1763, the British under Jeffrey Amherst used blankets exposed to smallpox as germ warfare in an attempt to subdue the First Nations resistance led by Obwandiyag (Pontiac). In 1775, during the American Revolution, American troops besieging Quebec City were stricken with smallpox.

Smallpox Epidemics on the Prairies

As European fur-trading posts moved west, so did the virus. From 1779 to 1783, smallpox spread to areas that now form parts of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Some communities of Plains Indigenous peoples lost 75 per cent or more of their members. It is estimated that more than half of First Nations people living along the Saskatchewan River (territory of the Nehiyawak, Saulteaux, Assiniboine and Niitsitapi) died of smallpox or epidemic-related starvation.

In 1838, a second smallpox epidemic struck the Prairies. The epidemic began with an infected person aboard an American Fur Company steamship on the Missouri River. The captain refused to halt or quarantine the ship. The virus eventually reached Forts Union and McKenzie, in what is now North Dakota and Montana. Traders representing various nations, including the Assiniboine and Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), frequented the affected American trading posts.

Hudson’s Bay Company employees started giving inoculations and teaching the technique to others after the two Prairie epidemics. Smallpox changed power structures and alliances, as well as land use and occupancy. Some distinct cultural groups disappeared as almost all of their members died. Survivors sometimes joined other ethnic groups.

Métis communities in what is now central Alberta experienced a smallpox outbreak in 1870. St. Albert’s Métis population declined by roughly 37 per cent that year.

Smallpox Epidemic in British Columbia

Smallpox first reached the Pacific Northwest in the late 18th century. In the late 1770s, the disease killed many members of Tlingit, Haida, Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Salish and Ktunaxa communities. In 1782, roughly two-thirds of the Stó:lō population died after contracting smallpox.

In 1862, a person infected with smallpox arrived in Victoria aboard a steamship travelling from San Francisco. The disease spread to an encampment north of the city, where traders from many First Nations stayed. The few efforts colonists made to control the disease were disorganized. Some demanded the eviction of Indigenous people from colonial communities to protect themselves from the disease. When the residents of the north encampment left for their homelands, the disease spread across the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. The disease had devastating impacts on many peoples, including the nations of Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw, Tlingit, Heiltsuk, Haida, Tsimshian and Tŝilhqot’in, as well as some Coast Salish and Interior Salish nations. On the coast alone, some 14,000 Indigenous people died, representing a loss of roughly half of the region’s population.

The 1862 epidemic left mass gravesites, empty settlements and grieving survivors. It also impacted governance in some nations. Stories, knowledge and skills were lost with those who carried them. The massive population decline paved the way for colonists to move further into Indigenous lands without establishing treaty relations. Fear of smallpox was one cause of the Chilcotin War of 1864 (see Tŝilhqot’in).

Vaccinations, Public Health and Resistance

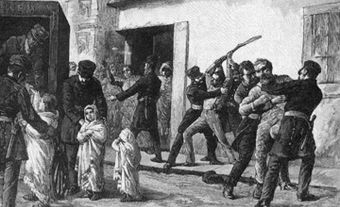

Beginning in 1768, arm-to-arm variolation, an inoculation using the live smallpox virus, became more widely practised in North America and helped limit the spread of the disease. Reverend John Clinch introduced a safer vaccine in North America in 1798. After Confederation, the provinces made it mandatory to vaccinate schoolchildren. They also passed laws allowing municipalities and townships to carry out general vaccination when an epidemic threatened. However, many people opposed mandatory vaccination. Anti-vaccinationists were critical of the unclean administration of vaccines and viewed vaccines as a way for public health units to avoid more costly sanitary measures. Some believed that vaccines would cause illness and suffering. Anti-vaccinationists also viewed mandatory vaccination as a breach of individual rights. Many French Canadians in Montreal opposed vaccination during a major smallpox outbreak in 1885. Riots broke out in the city, in part as a response to officials’ attempts to enforce control measures.

By Henri Julien. More information about this image: artifact M993X.5.1135.

Twentieth Century and Eradication

Modern smallpox vaccine production began in Canada in 1916. Nevertheless, a notable outbreak occurred in Windsor, Ontario in 1924. Sixty-seven unvaccinated people contracted the disease and thirty-two died. Smallpox persisted in Canada until 1946, when vaccination campaigns eliminated it. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it globally eradicated in 1979 after a 10-year campaign in South America, Africa and Asia. Smallpox is the first major disease to have been wiped out by public health measures.

Canadian scientists played a key role in the eradication. Connaught Laboratories, based in Palmerston, Ontario, consulted on vaccine production across the Americas. Between 1980 and 2001, Connaught and its successors kept smallpox samples in a deep-freeze in case the vaccine was needed in the future. After 9/11, in the context of new fears of bioterrorism, pharmaceutical company Aventis Pasteur retrieved the stocks to create a new stockpile of the vaccine.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom