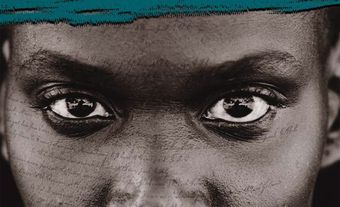

In early Canada, the enslavement of African peoples was a legal instrument that helped fuel colonial economic enterprise. The buying, selling and enslavement of Black people was practiced by European traders and colonists in New France in the early 1600s, and lasted until it was abolished throughout British North America in 1834. During that two-century period, settlers in what would eventually become Canada were involved in the transatlantic slave trade. Canada is further linked to the institution of enslavement through its history of international trade. Products such as salted cod and timber were exchanged for slave-produced goods such as rum, molasses, tobacco and sugar from slaveholding colonies in the Caribbean.

This is the full-length entry about Black enslavement in Canada. For a plain language summary, please see Black Enslavement in Canada (Plain Language Summary).

(See also Olivier Le Jeune; Sir David Kirke; Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada; Underground Railroad; Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; Slavery Abolition Act, 1833; Slavery of Indigenous People in Canada.)

Terminology

There is debate about the terms enslavement and enslaved people, on one hand, and slavery and slaves on the other. Many authors and historians use both sets of terms, which have similar meanings but can represent different perspectives on historical events. For example, slave is used to describe a person’s property. It is a noun that critics of the term say reduces a person to a position they never chose to be in. The term enslaved describes the state of being held as a slave. Historians who prefer enslaved person explain that it makes it clearer that enslavement was imposed on people against their will. They also mention that adding the word person brings forward the humanity of the people the term describes.

Some historians continue to use the terms slave and slavery, without adding person, arguing that the terms are clearer and more familiar. They argue that adding the word person implies a level of autonomy that enslavement took away from people.

Enslavement in New France

In the early 17th century, French colonizers in New France began the practice of chattel slavery, in which people were treated as personal property that could be bought, sold, traded and inherited. The first slaves in New France were Indigenous peoples a large percentage of whom came from the Pawnee Nation located in present-day Nebraska, Oklahoma and Kansas. Many were captured during war and sold to other Indigenous nations or to European traders. Some French colonists acquired enslaved Black people through private sales, and some received Indigenous and African slaves as gifts from Indigenous allies. Out of approximately 4,200 slaves in New France at the peak of slavery, about 2,700 were Indigenous people who were enslaved until 1783, and at least 1,443 were Black people who were enslaved between the late 1600s and 1831. The rest of the slaves were from other territories and other countries. Over time, enslaved people from any Indigenous group in North America were generally referred to as panis — a term that became synonymous with “enslaved Indigenous person.” Indigenous and African individuals held in bondage were also commonly referred to as domestiques or servants — words that almost always meant slave. (See also Slavery of Indigenous People in Canada.)

(courtesy Native Land Digital / Native-Land.ca)

The earliest written evidence of enslaved Africans in New France is the recorded sale of a boy from either Madagascar or Guinea believed to be at least six years old. In 1629, the child was brought to New France by the Kirke brothers, who were British traders (see Sir David Kirke). The boy was first sold to a French clerk named Olivier Le Baillif (sometimes referred to as Olivier Le Tardiff),. When Le Baillif left the country, the little boy was given to Guillaume Couillard, who sent the boy to school. In 1633, the enslaved boy was baptized and given the name Olivier Le Jeune.

Did you know?

Olivier Le Jeune’s burial record, dated 10 May 1654, lists his occupation as domestique. It appears that he served the Couillard household for approximately 26 years under this status. It was common for a slave to be called a domestique in Quebec records. It is, however, unclear to historians whether Olivier died a chattel slave under the Couillards, or as a free man who had chosen to remain in their service.

The next enslaved African in New France was a man named La Liberté, who appears in the 1686 census records. At that time, there was a growing demand for enslaved Black people as a source of labour to avoid paying costly European workers.

On 1 May 1689, King Louis XIV officially authorized the importation of enslaved Black people to New France. However, this commercial endeavour was stalled two weeks later when France entered the War of the League of Augsburg (1689–97), and again in 1702 with the start of Queen Anne’s War (1702–13). Despite the setback, 13 enslaved Black people were brought into New France through private sales. A much larger shipment of enslaved Black people that had been authorized by the king did not arrive.

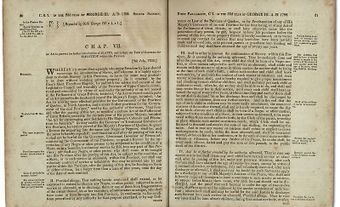

On 13 April 1709, Intendant Jacques Raudot passed a colonial law entitled Ordinance Rendered on the Subject of the Negroes and the Indians called Panis. It legalized the purchase and possession of slaves in New France and further solidified the practice of enslavement. It was the first official legislation on slavery in New France. Black enslavement was reinforced by the next French king, Louis XV, who made two proclamations about slavery in the 1720s and one more in 1745.

Enslavement in British North America

When the British conquered New France in 1760, the Articles of Capitulation, signed at the surrender of Montréal on 8 September 1760, included a specific clause on enslavement. Article XLVII stated:

The Negroes and panis of both sexes shall remain, in their quality of slaves, in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong; they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the colony, or to sell them; and they may also continue to bring them up in the Roman Religion.

—“Granted, except those who shall have been made prisoners.”

This clause stated that French inhabitants would not lose their slave property under the British regime, and reinforced enslavement as legal under British rule. Article XLVII also illustrates that there were enough enslaved people in New France to warrant a separate clause in the capitulation of an entire colony.

Saint John’s Island (changed to Prince Edward Island in 1799) was the only jurisdiction in British North America that passed a law regulating the enslaved. An Act, declaring that Baptism of Slaves shall not exempt them from Bondage became law in 1781. It stated that Black people “who now are on this Island, or may hereafter be imported or brought therein (being Slaves) shall continue such, unless freed by his, her, or their respective Owners.” This legislation was introduced to protect the personal property of existing and future settlers. There were three main provisions: baptism did not change slave status, persons enslaved in Prince Edward Island remained so unless manumitted (set free) by their owners, and children born to enslaved women were born enslaved. To encourage White settlers to relocate to the Island, an Act of Parliament was instituted in 1791 offering “forty shillings for every Negro brought by such white person.”

After the British were defeated in the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), the number of enslaved Africans in British North America increased significantly. To encourage White American settlers to immigrate north, the government passed the Imperial Statute of 1790, which allowed United Empire Loyalists to bring in “negros [sic], household furniture, utensils of husbandry, or cloathing [sic]” duty-free. By law, such chattel could not be sold for one year after entering the colonies.

Around 3,000 enslaved men, women and children of African descent were brought into British North America. By the 1790s, the number of enslaved Black people in the Maritimes (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island) ranged from 1,200 to 2,000. There were about 300 in Lower Canada (Québec), and between 500 and 700 in Upper Canada (Ontario).

Did you know?

During the American Revolutionary War, thousands of free or enslaved Black people fought for the British, hoping to gain their freedom along with the promise of land. By 1783, when the Treaty of Paris was signed, British forces and their allies fled to locations such as Europe, the West Indies (the Caribbean) and the Province of Québec (divided in 1791 into Upper Canada and Lower Canada). Between 1783 and 1785, more than 3,000 free Blacks or former enslaved people settled in Nova Scotia, where they faced hostility, racial segregation, low-paying jobs and inequality (see Black Loyalists in British North America and Arrival of Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia).

Slave Ownership in Canada

Slave owning was widespread in colonial Canada. Individuals from all levels of society owned slaves, not just the political and social elite. People who enslaved Black persons included government and military officials, disbanded soldiers, Loyalists, merchants, fur traders, tavern and hotel keepers, millers, tradesmen, bishops, priests and nuns. While slave ownership filled a need for cheap labour, it was also considered part of an individual’s personal wealth. The law enforced and maintained enslavement through legal contracts that detailed transactions of the buying, selling or hiring out of enslaved persons, as well as the terms of wills in which enslaved people were passed on to others.

In early Canada, some slave owners held a small number of slaves, while others had more than 20. Father Louis Payet, the priest of Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, Québec, owned five slaves — one Indigenous and four Black. James McGill, member of the Assembly of Lower Canada and founder of McGill University, counted six enslaved Black persons as part of his property holdings. Boatswain and Jane were both owned by Loyalist widow Catherine Clement in Niagara, where they were advertised for sale in the Niagara Herald in 1802. Noted deputy superintendent of the Indian Department, Matthew Elliott, is known to have held at least 60 enslaved Black people on his large estate in Fort Malden, Ontario (present-day Amherstburg). British army officer Sir John Johnson brought 14 Black slaves with him to early Canada. Prominent military officer and merchant John Askin bought and sold as many as 23 slaves on both sides of the Detroit River. James Girty traded with, and was an interpreter for, the Indigenous peoples in the Ohio region. He owned at least three enslaved Black people in Gosfield Township in Essex County, Ontario. One of his slaves — Jack York — was accused of an offense against a White woman and was sentenced to be hanged. However, Jack escaped before the sentence could be carried out.

In what are now the Maritime provinces, many people owned slaves. Two businessmen in Saint John, New Brunswick, advertised the sale of their Black slaves in a local newspaper. These men were Loyalist James Hayt and Thomas Mallard, who was owner of Mallard House inn, which was used as the site of the first parliament of New Brunswick in 1786. Halifax merchant Joshua Mauger traded Black slaves; and in Liverpool, Nova Scotia, businessman and diarist Simeon Perkins purchased a 10-year-old Black boy and changed the boy’s name from Jacob to Frank. Baker Richard Jenkins, merchant William Creed, and Loyalists Colonel Joseph Robinson, Governor Walter Patterson, merchant Thomas Haszard and businessman William Schurman, were a few businessmen who brought enslaved Black people into Prince Edward Island. A number of the slaves were from Africa. In Newfoundland, merchant and fisherman Thomas Oxford’s Black male servant was stolen from him in 1679.

The wills of some slave owners in the Maritimes freed their slaves when the owner died. Upon his death in 1791, magistrate John Benger freed a man, woman and three children. Similarly, in 1814, when John Ryan, founder of the Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser, passed away, he emancipated his Black slave Dinah. Her two children were freed when they reached the age of 21.

In Upper Canada’s Town of York (what is now Toronto), the six enslaved Black people owned by Provincial Secretary of Upper Canada, William Jarvis, were counted in the 1799 census. Sophia Pooley, kidnapped and sold into slavery at age nine, was one of several individuals of African descent whom Mohawk chief Joseph Brant enslaved in the Burlington area.

Slave ownership was prevalent among the members of the early Upper Canada Legislative Assemblies, as well. Six out of the 16 members of the first Parliament of the Upper Canada Legislative Assembly (1792–96) were slave owners or had family members who owned slaves: John McDonell, Ephraim Jones, Hazelton Spencer, David William Smith, and François Baby all owned slaves, and Philip Dorland’s brother Thomas owned 20 slaves. Dorland was replaced in Parliament by slave owner Peter Van Alstine. And the following six out of the nine original members of the upper house of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada were also slave owners and/or members of slaveholding families: Peter Russell, James Baby, Alexander Grant Sr., Richard Duncan, Richard Cartwright and Robert Hamilton. Peter Russell, the first receiver and auditor general of Upper Canada, had a free Black man named Pompadour working for him. But Pompadour’s wife Peggy and their three children Jupiter, Amy and Milly were enslaved by Russell.

The following 14 out of the 17 members of the second Parliament of the Upper Canada Legislative Assembly (1797–1800) either enslaved Black people or were from slaveholding families. David W. Smith, who was serving his second term in the Assembly, was a slaveholder. Thomas Fraser, who owned four slaves in the District of Johnstown, was the district’s first sheriff and came from a Loyalist slaveholding family. Richard Beasley owned several slaves in Hamilton, and Richard Norton Wilkinson was in possession of a Black woman and two Black children. Thomas McKee came from a slave-owning family and enslaved eight Black people himself. Dr. Solomon Jones purchased an eight-year-old Black girl from his brother Daniel in 1788, and Timothy Thompson owned a number of enslaved Black people in the Midland District (see Midland). Robert Isaac Dey Gray was Upper Canada’s first solicitor general, and became a slave owner when his father, Major James Gray, died, leaving him a Black woman named Dorinda Baker and her sons Simon and John. Benjamin Hardison owned Chloe Cooley before selling her to Adam Vrooman. Samuel Street and his business partner Thomas Butler (son of Colonel John Butler of Butler’s Rangers) dealt in the sale of many goods, including enslaved people. In 1786, they sold “a Negro wench named Sarah about nine Years old” to Adam Crysler for £40. William Fairfield and Edward Jessup Jr. were also from families that enslaved Black people. And lastly, Christopher Robinson was from a family that enslaved Black people and was also the sponsor of the 1798 Bill to authorize and allow persons coming into this Province to settle to bring with them their Negro Slaves. Though the bill passed the first three readings in the Assembly, the Legislative Council tied up the bill until the close of the parliamentary session, and in doing so prevented it from becoming law. The introduction of this bill reflected an opposition to the abolition of slavery in the province.

Members of Nova Scotia’s Legislative Assembly were also slave owners. James DeLancey and Major Thomas Barclay, both of whom served in the 6th General Assembly (1785–93), owned six and seven slaves respectively. James Moody, who sat in the 7th General Assembly (1793–99) possessed eight slaves. John Taylor, who was a sitting member in the 8th General Assembly (1799–1806), held six Black people in bondage.

Slave Labour: Forced to Work for Free

French and English colonies depended on slave labour for economic growth. The intention of enslaving Black people was to exploit their labour. Colonists wanted free labour to increase their personal wealth, and in turn, enhance local and colonial economies. In Canada, the majority of enslaved people worked as domestic servants in households, cooking and cleaning, and taking care of their owners’ children. Many were employed in the businesses of their owners, including for example inns, taverns, mills and butcher shops. Enslaved Black people cleared land, chopped wood, built log homes and made furniture in the colonies. As agricultural workers, they prepared fields, planted and harvested crops and tended to livestock. Many also worked as hunters, voyageurs, sailors, miners, laundresses, printing press operators, fishermen, dock workers, seamstresses, hair dressers and even as executioners. Slave labour was used to make a range of products, such as potash, soap, bricks, candles, sails and ropes. Enslaved males were trained and employed in skilled trades such as blacksmiths, carpenters, cobblers, wainwrights and coopers. They were often “hired out” as a way for slave owners to earn more money on their investment. Enslaved Black people laboured long hours, doing physically strenuous tasks, and were always at the beck and call of their masters.

Treatment

A persistent myth suggests that people enslaved in Canada were treated better than those enslaved in the United States and the Caribbean. But since the belief that Black persons were less than human was used to justify enslavement in all three places, it stands to reason that the treatment of enslaved Black people in Canada was comparable.

As chattel, they had no basic rights or freedoms and they were either treated humanely or cruelly, depending on their slave master. For instance, some slave owners allowed enslaved Africans to learn to read and write, while enslaved children were often denied an education. A number of enslaved Black people were freed upon their owners’ death, and some were rewarded for their years of service with inheritances of land, money and household properties. Other slaves were passed on to family members or friends upon their owner’s death. Many enslaved Black people were subjected to cruel and harsh treatment by their owners. Some Black slaves were tortured and jailed as punishment, others were hanged or murdered. Enslaved Black women were often sexually abused by their masters. Families were separated when some family members were sold to new owners.

The treatment of enslaved Black people varied, but the mere fact that they were held as property sums up their overall social condition.

Resistance

Black people resisted enslavement in different ways. Some enslaved Black people, mainly women, left their owner’s property for short periods of time without permission. This was called petit marronage. Other forms of personal rebellion included pretending to be physically or mentally ill, or lying and scheming to find ways to get out of slave labour. Others made the biggest form of protest by running away in pursuit of their liberty.

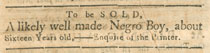

Many enslaved Black people in Upper Canada fled to free regions in the United States, including the former Northwest Territory (which included parts of what is now Michigan and Ohio), Vermont, and New York — states that banned slavery in 1777 and 1799, respectively. Dozens of runaway slave ads were published in newspapers in Canada and the newly formed United States. The ads included detailed descriptions of an escapee’s physical appearance, the clothes they were wearing and the languages he or she spoke. Rewards were frequently offered, along with warnings not to employ or give refuge to the runaway. In 1798, Henry Lewis — who was enslaved by William Jarvis — fled to Schenectady, New York, to secure his freedom. Some individuals launched legal challenges against their owners to fight against their slave status and treatment. (See also Marie-Joseph Angélique and Chloe Cooley.)

Legal Challenges to Enslavement

The abolitionist movement in Britain had argued against the transatlantic slave trade since the 1770s. Abolitionism soon made its way to British North America, where a number of legal challenges were made against the institution of slavery. By the early 1800s, Lower Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia had attempted to abolish slavery but failed. Bills were introduced in Lower Canada in 1793 and in 1801, but neither bill was passed. In contrast, bills to legalize enslavement were presented in New Brunswick (1801) and Nova Scotia (1808), but they were met with opposition and were not passed. Meanwhile, enslaved individuals launched legal challenges during the late 18th century that destabilized the institution of enslavement in Québec and the Maritimes.

Between 1791 and 1808, enslavement was challenged by Nova Scotia’s Chief Justice Thomas Strange and his successor Sampson Blowers. When slave owners came before Strange and Blowers seeking to reclaim enslaved people who had fled their bond, the judges put the burden of proof on the slave owners, asking them to prove ownership of the enslaved person and to prove that they had the legal right to purchase that person. Owners who appeared before these judges were usually unable to satisfy the court in that regard. Among other factors, the strong opposition of the courts, along with the slave owners’ inability to protect existing slavery laws, made enslavement in Nova Scotia economically unviable. As a result, slavery gradually died out.

A precedent-setting case came before the courts in Lower Canada in February 1798. An enslaved woman named Charlotte was arrested in Montréal after leaving her mistress and refusing to return to her. She was brought before Chief Justice James Monk, who released her based on a technicality. British law stated that enslaved persons could only be detained in houses of correction, not in common jails. Since no houses of correction existed in Montréal, Monk decided that Charlotte could not be detained. The following month, another enslaved woman named Jude was freed by Monk on the same grounds. Monk asserted in his ruling that he would apply that interpretation of the law to all future cases.

In 1800, an enslaved Black woman named Nancy sought her freedom in the New Brunswick courts on a writ of habeas corpus — a law wherein an individual can report unlawful detention or imprisonment. During the hearing, the court decision was a tie, so Nancy remained in the service of her master Caleb Jones. The writ was not issued until 14 years after Nancy had attempted to emancipate herself and her young son by escaping enslavement. However, such cases placed limitations on enslavement, making the practice insupportable. The Supreme Court’s anti-slavery position helped to decrease the value of slave property, due to the uncertain future of enslavement. People would not purchase slaves without solid proof of ownership. Slave owners knew they could not count on the courts to recognize an owner’s right to hold slaves, or to help maintain the practice of enslavement if any related legal issue arose. Enslaved people increasingly refused to be held in bondage and knowing they had the backing of the courts, many chose to self-emancipate. Consequently, many slave owners suffered financial loss.

In Prince Edward Island in 1802, the lawyer for a captured runaway named Sam demanded that the owner, Thomas Wright, provide proof of ownership. However, Wright had all of his paperwork in order and was able to reclaim Sam. In 1825, the 1781 Act regulating enslavement in that colony was reversed without debate, seemingly affirming that enslavement was then illegal in PEI.

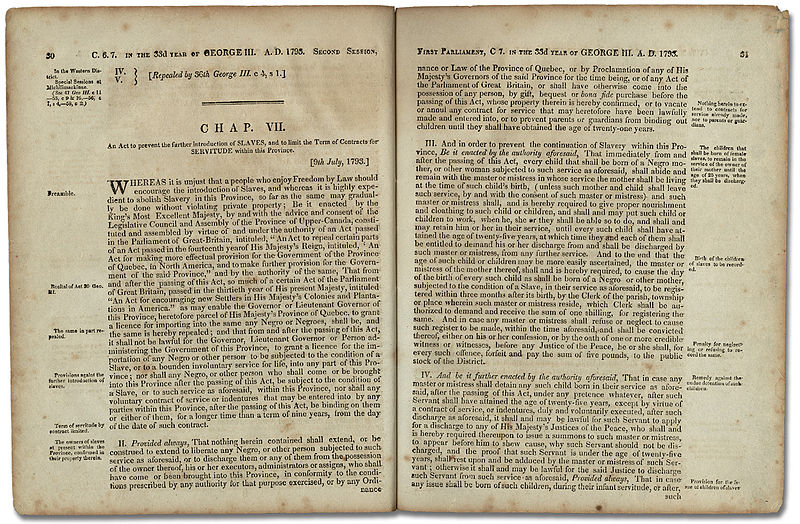

In Upper Canada, the tide was also changing. Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe held anti-slavery sentiments influenced by the growing movement in Britain. In 1793, Simcoe and Attorney General John White used the Chloe Cooley incident as means to introduce a bill to end slavery in that colony. However, it met strong opposition, since many of the members of both houses of the legislature enslaved Black people or were from slaveholding families. The amended compromise was the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, which received Royal Assent on 9 July 1793. This was the first piece of legislation passed in the British colonies to limit slavery. The Act did not abolish the practice nor emancipate a single enslaved person. It instead placed limitations on enslavement. Importing enslaved people became illegal, and a time frame was set in place to gradually phase out slaveholding.

Abolition

Although the practice of enslavement had decreased considerably by the 1820s, it remained legal in British North America. The children born in 1793, when the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada took effect, turned 25 by 1818. Therefore, they were no longer slave property and their children were born free. However, a very small number of Black people — less than 50 — remained in bondage. In March 1824, in one of the last recorded sales of a slave in Upper Canada, Eli Keeler of Colborne sold 15-year-old Tom to William Bell in Thurlow (now Belleville). In his 1871 obituary, John Baker was recognized as the last surviving enslaved Black person born in Canada.

As it did in Québec and Nova Scotia, the practice of enslavement eventually came to an end in New Brunswick when supporters of slavery could not get a law passed to confirm the legality of enslavement. In 1825, Prince Edward Island reversed its only regulation on enslavement.

During the period of abolition, there was a move to replace enslavement with indentureship in order to benefit both slave owners and the enslaved. Indentureship meant that persons once enslaved were paid for their labour, serving their former masters or other employers for a specific length of time before becoming free. Indentureship was a generally accepted practice across British North America adopted by many slave owners to avoid further losses through slaves running away. Indentureship was also supported through legislation, as outlined in laws such as the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery, which limited the time that formally enslaved persons were bound to service to nine years.

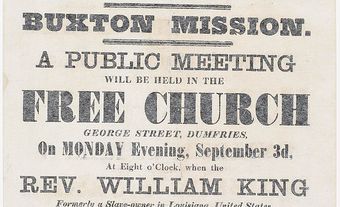

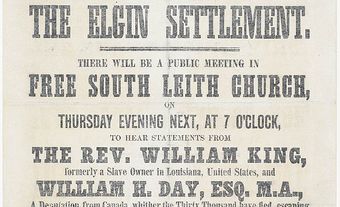

Anti-slavery legislation was introduced in Britain and received Royal Assent on 28 August 1833. The Slavery Abolition Act came into effect on 1 August 1834, abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire, including British North America. The Act made enslavement officially illegal in every province and freed the last remaining enslaved people in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom