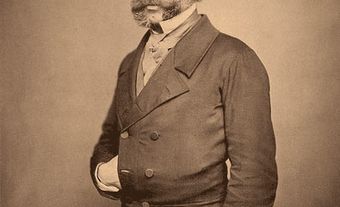

Sir William Edward Parry, naval officer, Arctic explorer (born 19 December 1790 in Bath, England; died 8 or 9 July 1855 in Bad Ems, present-day Germany). Parry was involved in four expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage: the first as lieutenant under Captain John Ross, followed by three of his own ventures. A fifth and final expedition attempted to locate the North Pole. While each of Parry’s ventures were unsuccessful, he made significant contributions to European knowledge of the Arctic. The Parry Islands in the Arctic Archipelago are named after him.

Early Life and Career

William Edward Parry was born in Bath in 1790 and educated at Bath Grammar School. In 1803, a family friend, Admiral William Cornwallis, brought Parry on board the Ville de Paris as a volunteer when demand for recruits was high as a result of the Napoleonic Wars. Although Parry had never been at sea, he quickly earned the respect of senior officers, marking the beginning of his naval career. From 1806 to 1817, Parry served on many ships along the French coast, in the Baltic and North seas and in North America before returning to England to be with his ailing father.

First Expedition: 1818

William Edward Parry’s first venture to the Arctic was in 1818, as lieutenant under Captain John Ross. Ross and his men were in search of the Northwest Passage — a sea corridor through the Arctic Archipelago. When the expedition reached Cape York, Greenland, they met a small number of Inughuit — a group of Greenlandic Inuit who were frightened by their first encounter with a ship and white men. Ross called the Inughuit “Arctic Highlanders.” The crew also saw what appeared to be red or pink cliffs north of Cape York. Ross called these the Crimson Cliffs — it was later discovered that the reddish colouring is a result of melting snow and microscopic algae, and it has come to be referred to as “watermelon snow.”

When the expedition returned to England, Parry was selected to lead the next Arctic expedition, as it was perceived that Ross did not make any significant contributions toward finding the Northwest Passage.

Second Expedition: 1819–1820

William Edward Parry’s expedition in search for the Northwest Passage brought him back to Lancaster Sound — where he’d previously been with John Ross — this time with HMS Hecla and HMS Griper. He wanted to determine if it was an inlet (an arm of the sea leading to a bay) or a sound (a sea or ocean channel between two bodies of land). The ships hit pack ice and Parry decided to travel south in hopes of finding a traversable path. Parry eventually returned north toward Devon Island, naming his route the Wellington Channel. The expedition then veered westward into Barrow Strait, giving Cornwallis and Bathurst islands their English names along the way. The expedition reached longitude 110°W off Melville Island on 4 September, resulting in a £5,000 sum from the British Government for making it that far west within the Arctic Circle. A piece of land on the island was named Cape Bounty in honour of the prize.

The expedition continued to Cape Providence before settling in for winter at Melville Island in what was called Winter Harbour. The crew prepared for winter by hunting and managing the supplies, which included dried vegetables. There was only one fatality out of the 94-member crew — other Arctic expeditions experienced higher death rates. The crew remained entertained by theatre performances put on by the officers and a newspaper edited by Captain Edward Sabine. The ships continued their westward expedition on 1 August 1820 when the boats were free from the ice, only to find more pack ice. The expedition was forced to return to England where Parry was elected a fellow of the Royal Society.

Third Expedition: 1821–1823

As with William Edward Parry’s earlier trips to the Arctic, the aim of the 1821–1823 expedition was again to find a Northwest Passage. This time Parry attempted to travel further south, but the HMS Fury and HMS Hecla reached an impasse at Repulse Bay. Inuit visited the crew, hunted for them, as well as gave them useful hunting techniques and guidance on where they might travel next. The expedition only made it to the waterway between Baffin Island and the mainland of present-day Nunavut, which he named the Fury and Hecla Strait, before having to settle for a second winter in Igloolik. The expedition returned home after the winter as some of the crew were starting to become weak with symptoms of scurvy.

Fourth Expedition: 1824–1825

While the 1821–1823 expedition did not find the Northwest Passage, William Edward Parry remained a well-respected explorer as he had helped uncover the region. In 1824, he was selected to lead another expedition with the Fury and Hecla, again in search of the Northwest Passage. The venture made it to Port Bowen, on the eastern side of Prince Regent Inlet, where it settled for winter. During the following summer, the Fury was abandoned due to damage. The crew moved to the Hecla and returned home.

Fifth Expedition: 1827

In 1827, William Edward Parry abandoned attempting to find the Northwest Passage, setting out instead to locate the North Pole. He sailed with the Hecla, reaching the Verlegen Hook Peninsula, Svalbard, before leaving the ship behind and continuing northward in two smaller boats. Limited supplies and a strong southward drift meant that the crew only made it to 82°45′ N — at the time, a record for the most northern latitude reached, but one that fell short of the North Pole. (See also Sir George Strong Nares.)

Parry was knighted in 1829 and took on various positions following his return from the 1827 expedition. Later, he helped prepare the Erebus and the Terror for Sir John Franklin's fateful 1845 expedition to find the Northwest Passage. When Franklin’s ships disappeared, Parry helped design a search expedition.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom